After the University of South Carolina’s women’s basketball team beat Oregon State on Easter Sunday to secure their fourth straight trip to the Final Four and continue their undefeated season, Gamecocks coach Dawn Staley gave an on-court interview to ESPN’s Holly Rowe while her players showered her with confetti. “If you don’t believe in God,” Staley said, “something’s wrong with you.”

Later, in the post-game press conference, she added, “He is Risen.” By “He,” Staley meant “Jesus Christ,” the God she has credited throughout the years for her team’s many successes. But there was something about her statements this time that seemed to hit a different chord, particularly Staley’s phrasing that there was “something wrong” with people who don’t believe in a higher power of some kind, though in Black American vernacular that phrase is often not used literally.

It’s not uncommon to hear athletes or coaches thank God after winning a game or a championship. But as an employee of a public educational institution, there is a fine line between a coach expressing their personal religious beliefs and venturing into advocacy and violating students’ First Amendment rights. Staley has toed that line for years—and, according to some people, has blatantly crossed it.

“She may have coaching skills that are exceptional, but her understanding of freedom of conscience is exceptionally bad. Her understanding of the law is exceptionally bad,” Annie Laurie Gaylor, co-president of the Freedom From Religion Foundation (FFRF), tells The Daily Beast. “She appears to have no boundaries when it comes to pushing religion on a captive audience of students dying to please her.”

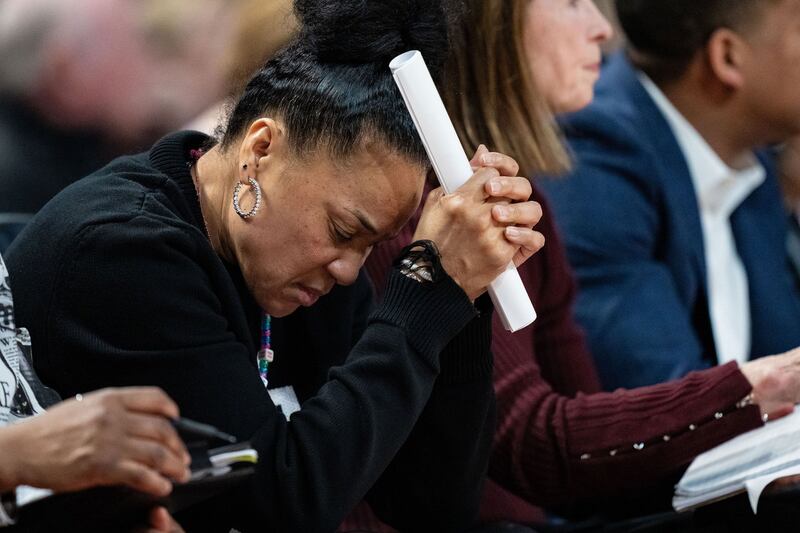

Dawn Staley reacts after the South Carolina Gamecocks defeated the UCLA Bruins in the 2023 Sweet Sixteen round.

Maddie Meyer/Getty Images/Maddie Meyer/GettyStaley is currently the best (and arguably the best-known) coach in women’s college basketball. In 2021, she signed a historic contract extension for seven years and $22.4 million, making her one of the highest-paid women’s basketball coaches in the country. Under her leadership, the University of South Carolina women’s basketball team has won two national championships, in 2017 and 2022. They won each of their first two games of this year’s tournament by more than 40 points and are many people’s favorite to win it all.

Staley is beloved by her players, who rave about the culture of her team, and she has had an outsized impact on the sport. She is known for her strong faith, and called the team’s 2022 championship “divinely ordered.” Last week, ahead of the Gamecocks’ first game in the tournament, Staley said that her team’s level of preparation earned them divine “favor.”

Her personal religious views are not an issue, of course—however, they may begin to become one when applied to her coaching duties at a public university. Staley has team meals before each game, which include a “Gameday Devotional” that she also posts to social media. The devotionals feature a photo of the team, the name of their opponent, and a Bible verse. During this year’s March Madness tournament, those have included Psalm 143:8 (“Let the morning bring me word of your unfailing love, for I have put my trust in you. Show me the way I should go, for to you I entrust my life”) and Jeremiah 31:3 (“I have loved you with an everlasting love”). On the back of the papers is an inspirational quote from a University of South Carolina WBB alum and, in the corner, one more thing: “Jesus vs [opponent],” with “Jesus” being her team.

Religious freedom is a constitutionally protected right, and South Carolina is a secular public institution. Not only does Staley preach during team meals, she literally calls her team “Jesus,” implying that their play is doing the will of Jesus Christ. By stating publicly that there is “something wrong with you” if you don’t believe in God, she could be seen as passing judgment on the religious views of other people. (The University of South Carolina did not return a request for comment for this story.)

These devotionals have garnered the attention of the Freedom from Religion Foundation, which calls them a violation of students’ First Amendment rights. They have been characterized as “coercive” and can make students who may choose to opt out feel isolated from their team. In a letter sent Monday to University of South Carolina President Michael Amiridis, obtained and reviewed by The Daily Beast, FFRF staff attorney Chris Line cites several federal cases that have established precedent, as well as Mellen v. Bunting from the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, which has jurisdiction over South Carolina. That case “extended the scope of… cases from primary and secondary schools to college-aged students.”

In Mellen v. Bunting, the court found that mealtime prayer at a state military college violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment by constituting a government advancement—and therefore endorsement—of religion. “The University of South Carolina’s authority over student athletes is similar to that of VMI in that much of the players’ conduct is closely monitored, directed and critiqued by coaching staff,” Line explained.

In a SCOTUS case, Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, even student-led organized prayer prior to a football game was found to violate the Establishment Clause because it was considered to be “both perceived and actual government endorsement of the delivery of prayer at important school events.” It’s possible that because of the organized nature of the team meals that Staley’s devotionals are given during, they could fall under the same “captive audience” criteria that the court cited in Santa Fe v. Doe, according to Jill Heinrich, a professor of education at Cornell College who studies separation of church and state in American public education.

Dawn Staley reacts in the second quarter during a South Carolina Gamecocks game against the Georgia Lady Bulldogs.

Jacob Kupferman/GettyStaley addressed the controversy regarding her post-game comments on X. “I am not ashamed to praise him for what he continues to do for me and mine,” she wrote. “If you’re a nonbeliever it wasn’t for you-wish you well with your beliefs.”

As the coach of a professional sports team, there is a lot more leeway in terms of what beliefs can be expressed—and how they can be expressed—because professional sports are not bound by separation of church and state in the way public educational institutions are. As the basketball coach for a secular, public post-secondary school, Staley acts as a representative of the state and is therefore beholden to certain laws.

“It does seem to be venturing into ‘advocacy’ and violating the Establishment Clause… where you’re trying to promote religion—and a specific religion,” says Heinrich.

While in the past the Supreme Court has continually struck down school-sponsored proselytizing in public schools, a 2022 case ruled in favor of a football coach who wanted to pray on the field after games (and who had a history of leading pregame sermons for his students)—the latest in a litany of legal wins for religious plaintiffs that some experts worry could set a concerning new precedent. And while it could be argued that Staley is posting her devotionals to a personal account, just last month SCOTUS Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote on behalf of the court that “the distinction between private conduct and state action turns on substance, not labels,” indicating that if a public official is using their personal account to post material related to their public position—as Staley does on hers—then it falls under the same level of scrutiny.

This kind of behavior is not uncommon in college sports. A 2015 report from the FFRF cited more than 25 public universities for allowing football coaches to impose their personal religion on players by hiring Christian chaplains. And students who choose to individually pray before a game, for example, are held to a different standard than a teacher or coach under the law because of the level of influence an authority figure has over their students, Heinrich explains.

“This is not unusual, we see a lot of coaches that abuse their authority,” says Gaylor. “And that’s what she’s doing.”

Christianity is a powerful force in American culture and it’s worth asking whether Staley’s behavior would have been allowed to continue as long as it has if it didn’t align with the dominant religion in this country. If a college head coach was sitting their team down for pre-game meals and citing text from the Quran or the Torah, or crediting Allah for their team’s tournament success, would it be met with the same collective shrug?

Nationally, 38 percent of young Americans identify as “non-religious” and America’s youngest religious groups are all non-Christian. Staley’s team is predominantly Black—while 75 percent of Black Americans are Christian, roughly one in five Black Americans are religiously unaffiliated. And the religious diversity on display during March Madness is sometimes quite visible—two players who wear hijabs competed this year (including during Ramadan), with North Carolina State’s Jannah Eissa heading to the Final Four on Friday to face off against Staley’s Gamecocks.

Staley is a basketball genius whose players love her. Regardless of her religious beliefs, her teams win because she is a good coach and the best players in the country want to play for her. She inspires them. She relates to them. Thanking God after a win is commonly accepted in the world of sports and if Staley wants to continue to do that, that’s her right, as long as she is using “God” in a general, civil sense of the word. Where it becomes a problem, according to Heinrich, is when she appears to be promoting a specific religion, by citing explicit religious texts or referring to a specific God, like Jesus.

Dawn Staley speaks to the media during a 2022 press conference.

Jared C. Tilton/GettyDirectly attributing her program’s success—and, by extension, her players’—to divine intervention is where experts say it starts to feel problematic. Not only does it rob Staley’s own coaching and the players’ performances of the credit it deserves, it implies that the players are part of some higher calling they didn’t necessarily consent to being implicated in.

“It takes away the glory from the players and their talents and skills,” says Gaylor. “And it makes it seem like the other team is disfavored by this omnipotent deity.” Believing that God cares whether you win a basketball game is “the ultimate chutzpah by people pretending to be humble,” she says.

The public narrative around Staley’s coaching has long been that her athletes chose to play for her. But the reason her rhetoric may be considered “coercive” is because players, especially as young people, are much more likely to grin and bear it even if the proselytizing makes them uncomfortable. As Line, the FFRF attorney, wrote to the university president, a promising young athlete may be willing to ignore it in order to play for and learn from Staley, who is one of the best to ever do it.

“Coaches exert great influence and power over student athletes and those athletes will follow the lead of their coach,” Line wrote. “This is especially true for powerhouse programs like the University of South Carolina’s women’s basketball team that have had so much success.”

These women are going to win championships because they put in the work, because they are talented athletes, and because Dawn Staley is an incredible coach. If a coach takes a job at a public, secular institution, they need to be willing to figure out a way to balance their personal beliefs with their team’s cultural practices. Being forced to sit through what amounts to Bible study should not be a requirement for playing under Staley.