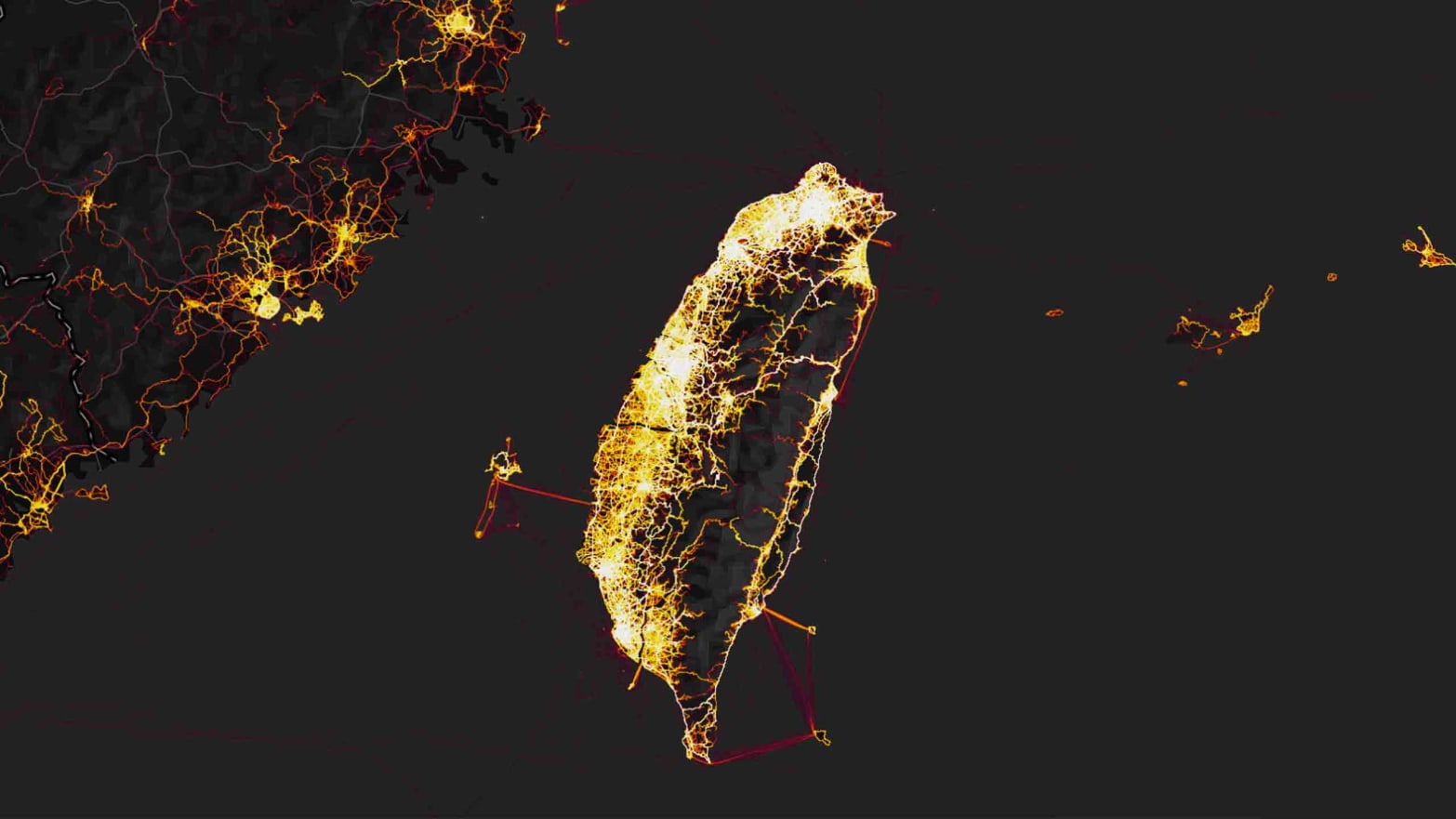

Over the weekend, internet users began to focus on a company called Strava that published a “heat map” showing its users around the world. Strava bills itself as a “social-networking app for athletes.” The “heat map” showed the location of all the rides, runs, swims, and downhills that its users have taken, as collected by their smartphones and wearables.

Of course, “athletes” doesn’t fully capture the universe of young, fit people. It suddenly occurred to, well, everyone, that another group likely to be avid users were military personnel. As you might imagine, the heat map shows many American and foreign military personnel are using the app, including the U.S. military presence in Niger. Over the past few days, people have used the heat map to spot and assess secret military bases in Syria, Yemen, and Turkey. At a basic level, it’s incredible to see people taking smartphone or other devices past checkpoints into places they really shouldn’t be. All this is bad, but wait, it’s worse.

Because as bad as the publicly available heat map is, the underlying data being freely uploaded to Strava is a security nightmare for governments around the world. Anyone with access to the data could make a pattern of life map for individual users, some of whom may be very interesting to foreign intelligence services.

It seems, for example, that there are some very avid users of this application in Taiwan.

Strava

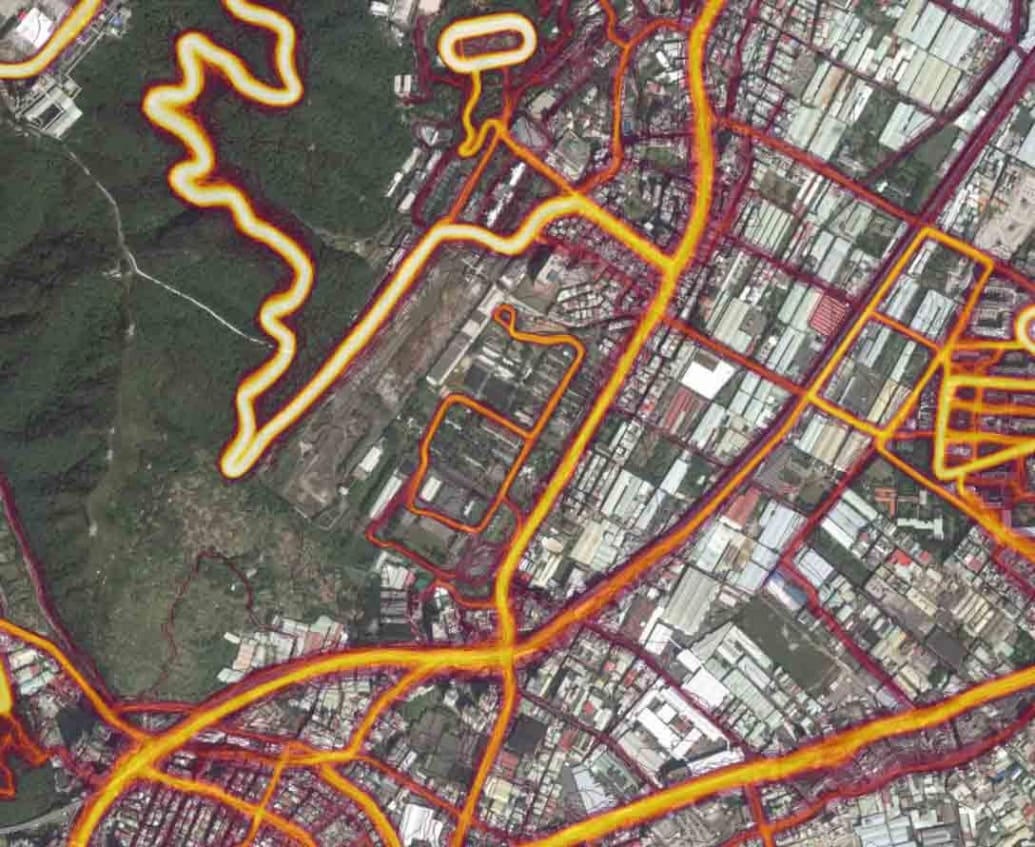

The site in the center is supposed to be fairly secret—it houses the headquarters of Taiwan’s missile command. Taiwan has deployed long-range cruise missiles that can strike mainland China across the Taiwan Strait and is, reportedly, developing even longer range missiles that can reach Beijing. In a war between China and Taiwan, an important priority for Beijing’s military will be to destroy these locations.

And so equally important for Taiwan is the ability to hide them. Taiwan took the secrecy of this place so seriously that, when it deployed cruise missiles for the first time, the military painted the heavy vehicles that launch them to look like delivery trucks. The ruse was pretty unsuccessful. The trucks looked like badly re-painted military vehicles (which they were). And the fictional company, called RED BIRD EXPRESS, wasn’t registered and didn’t have a website or phone—which most real business do since they want customers to contact them. Local reporters and netizens quickly sussed out the scheme and bloggers found the vehicles parked at the headquarters for Taiwan’s missile command.

This was a huge embarrassment to Taiwanese officials, who admitted the whole idea was “stupid” and then responded by… putting a roof over the parking lot where the trucks with missiles are still parked.

Taiwan did not move the base, though. And, as you can see, there are a number of avid Strava users who work there, causally jogging right by the parking lot where the missile launchers are parked.

Strava

At some level, we might say this is no big deal. After all, everyone knows there are missiles located at this site. I mean, the front gate even has a series of missiles on display. Everyone knows what’s underneath the roof. The security of this site was blown a long time ago.

Google Earth

Now here is the problem. This is only one of several missile bases in Taiwan—an important one, to be sure, but there are others, and some of those locations may still be secret. (At the Middlebury Institute of International studies at Monterey, we try to track these bases pretty closely. We’re confident we know where several are located, for example, but not all of them.) But Strava’s database has one more piece of information, one that is not accessible through the heat map but would be to the company, any client which might purchase the data and any hacker that might steal it. Strava knows which user made each track. That’s charming when it’s a celebrity uploading a run. But what about a soldier? Soldiers, remember, rotate from one assignment to the next. Which means Strava can continue to track each user as he or she rotates to the next assignment, burning one secret missile base after another with all those calories. Yes, if our user casually jogging by Taiwanese missiles day-after-day suddenly appears deployed to a new location, well that’s very interesting if you are targeting missiles for China’s Rocket Force.

A fair amount of personal data appears to be shared willingly by users, more than enough to make me uncomfortable. A bigger concern, of course, is whether hackers might be able to breach security and get at the data marked private. If I were a Strava employee, I’d be very careful about what sort of email links I clicked on.

Even if these users are careful to never make such a mistake again, continuing to use this app will allow anyone with access to the data to make good guesses about where the user lives and works, based on exercise locations. After all, don’t you usually think about picking a gym that’s close to home or to work? When you are done with a run, don’t you want to be close to a shower? Once this user demonstrates that he or she has access to sensitive locations by literally jogging through one, then every other ride, run, swim, or ski becomes useful information. One can infer the locations of bases based on where groups of “interesting” joggers live or where they turned off their phones. It’s even nice to see when they are on vacation, skiing in the mountains, or too busy doing something else to exercise (like training.) Really, the possibilities are endless if you are clever about this sort of thing.

None of this is to blame Strava, of course. It provides a service that lots of people obviously find useful. I myself could use to lose a few pounds. And, of course, it isn’t like Taiwan’s efforts at secrecy were super impressive to begin with. No one is really at fault here, other than individual users who may have violated security procedures. What the heat map does illustrate, though, is that we’re living in a very different age than the one where we developed a lot of our ideas about deterrence and strategic stability.

The notion that missiles on trucks would be nearly impossible to track made a lot of sense back when people didn’t carry around telephones with digital maps and before they wore watches that connected to the internet. It’s not as simple as just asserting that secrecy is doomed, but keeping secrets is a lot more complicated than before. And that means, in a crisis, it’s also a lot more complicated to know whether missiles that have been hidden away might survive, or whether you need to use them before you lose them.

So think about it before you upload your run through a sensitive military site. You might well be providing an adversary with information that could be used to kill you. Or not. But either way, go ahead and take that run. You’ll want to leave a good lookin’ corpse if at all possible.