The memoir of divorce is something of a cliché: a writer’s post-trauma, woe-is-me catharsis; the gory details from an unhappy marriage dumped on the page. It is written specifically for the divorced or lovelorn, who internalize the author’s emotional collapse and ensuing self-help prescriptions.

Even when written well—with a fair amount of objectivity and respect for the former spouse—the divorce memoir is still too often cringeworthy, discomfiting, and formulaic.

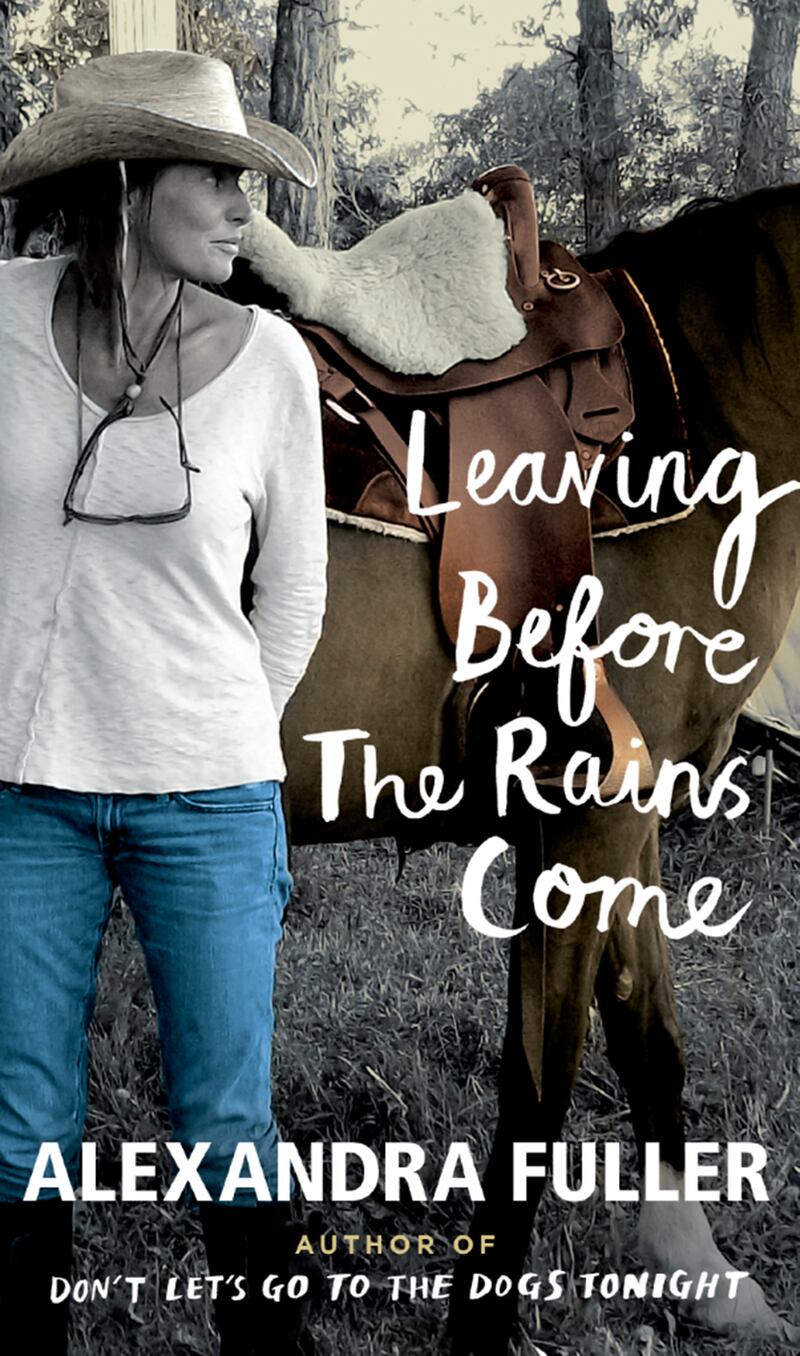

But Alexandra Fuller pulls it off in her latest book Leaving Before the Rains Come, an account of the collapse of her marriage weaved into vignettes of her complicated upbringing in colonial South Africa and displaced housewife-dom in the snow-capped mountains of Idaho and Wyoming, where she moved with her now ex-husband in her early 20s.

Fuller knew well the trappings of the break-up memoir before writing her own. She’d purchased dozens of them secondhand, seeking advice when her own marriage was floundering, and was, she writes, “distressed to find that many came in the telltale, rippled condition of women on the brink; read in the bath, wept upon, or both.”

She found them all tediously prescriptive—“like alcoholic memoirs and their twelve steps to freedom and recovery”—and quickly tired of the invariable “woman collapsing with grief on the kitchen or bathroom.”

Today, she is less critical of the sob stories and variations on the hackneyed Eat, Pray, Love tours that end with a new man and renewed faith in love.

“I love what Adrienne Rich said: ‘When a woman tells the truth she is creating the possibility for more truth around her,’” Fuller tells me, quoting the late, celebrated feminist writer, adding that she’s “grateful for Elizabeth Gilbert and for Cheryl Strayed, even though their books weren’t my map.”

Fuller is garrulous and warm, as passionate and quick-witted in person as she is in her writing. She has traveled to New York City for an appearance at Barnes & Noble, which was cancelled due to a blizzard that would shut down the city’s transportation later that night.

None of it fazes Fuller, who still lives in Wyoming and is content getting stuck in, drinking beer at an Irish pub in Manhattan all afternoon. At 45, Fuller is ageless and disarmingly beautiful, with a ruddy, Wyoming-winter complexion, fierce free spirit, salubrious appetite for alcohol, and dry, self-deprecating sense of humor.

“Don’t try reining me in,” she says, ordering a second beer. “The last man who tried it fell off a horse.” She’s referring to her ex-husband, Charlie Ross, an American, who suffered a near-fatal accident while playing polo a year before their 20-year marriage ended in 2012. (They had three children, now aged 21, 17, and 9.)

“I’m unconventional and eccentric and talk things out, and it seemed that the person I married—maybe in reaction—got quieter and more conventional over time,” she says. “It felt as if we were putting each other in a straitjacket.”

It would be a memoir about death—not divorce—that resonated most with Fuller as she observed her marriage’s dissolution.

“Oddly what came closest for me was Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, because for me the end of a marriage felt like a death. And it was really a death of self for me,” she says. “Both of you are attacking the monster and neither one of you can come to an agreement on how to kill it, because what you’re really saying to each other is, I can’t be authentic around you.”

Leaving Before the Rains Came is Fuller’s third memoir, and to an extent it revisits the subjects of her first two books. Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight (2001) was a love story, she says, to her early childhood as a white girl in what was then war-torn Rhodesia, while Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness (2011) was a love story to her eccentric, politically incorrect family, specifically her mother.

In this latest memoir, Fuller manages to describe aspects of her background afresh.

Born in England, Fuller moved to Rhodesia in 1972 when she was two, then to Malawi after the Rhodesian civil war ended, finally settling in Zambia. She grew up surrounded by chaos, danger, tragedy, and adventure. AIDS and malaria were rampant (Fuller came down with the latter on her wedding day, and the disease frequently infected her household).

Fuller learned from an early age to spot a landmine and wield her father’s rifle. Her parents lost three young children, one of whom drowned under Fuller’s watch.

Fuller was 23 when she married Ross, who was outdoorsy—skilled at whitewater rafting and polo—and seemingly fearless. She saw in him someone who could match her derring-do while also being a calming, stabilizing force after years of reveling in chaos with her family.

When I ask if she and her ex-husband agreed politically, she shakes her head. “Politically we were just…” She makes an explosion sound, implying they most certainly did not. “But I think so few of us have to put a gun behind our ideology. We can sit here in this country and say whatever we want without consequences. There are real consequences when women speak out. It’s really dangerous and it takes real courage. We are still speaking out against a white male majority. Forget the glass ceiling. We haven’t even broken the glass floor!”

As for her own marriage, “I believed that if I moored myself to Charlie, I would know tranquility interspersed with organized adventure,” she writes. She envisioned their life being like “‘Out of Africa’ without the plane crashes, syphilis, and Danish accent.”

It didn’t go as planned. “Everyone says marriage is hard work, but they don’t tell you that actually being yourself and respecting yourself is hard work,” she says.

If they didn’t say it outright, friends and in-laws, she felt, thought that she was lucky to be married and living in the U.S., given where she’d come from. She was enraged when NPR’s Scott Simon suggested the same to her during a recent interview.

“He said that he’d been to a lot of war zones and that a lot of people would be grateful to get out of a war zone and sell real-estate. It was so misogynistic. First of all I was 11 when I got out of a war zone, too young to sell real estate. Second of all my husband was the one who ended up selling real estate and he never lived in a war zone,” she says.

Fuller was even more enraged that NPR edited out this part of their interview. “At one point he implied, ‘Wasn’t your husband just providing for the family?’ I was so flummoxed by the question that what I didn’t say to him was, ‘So was I, actually.’ I had equal say in how the culture of our family went forward.”

Fuller thinks that “one of the things we’re starting to talk about as female writers and mothers is that my first job is to protect my children, no matter how cavalier I sound. They don’t need to be privy to my private life with their father. That’s unfair and that’s out of this book. Save it for the shrink. Yes my book is self-involved. It’s a memoir, and how many more memoirs do we need about a white female divorcee? But I think the job of a memoir, if it’s written well, is to make it universal. If it resonates with you, groovy. If it doesn’t that’s fine too. It isn’t about divorce.”

Writing, for her, is far from easy. She likes to be appreciated for her work—and what it takes to produce it. “It’s human to want support, to want people to recognize that I didn’t just wake up one morning and say, ‘Thank God for me, I just got a divorce and want something to write about.’ I’m a working writer, this is my job. So it matters to me that it’s good. I sweat over every word. I don’t just vomit this stuff up. It’s agony. The only thing that comes close is childbirth, except it’s like being in labor for eighteen months.”

Fuller is now in a new relationship: she has been seeing Wendell Field, an artist based in Jackson Hole, for eight months. They met when she bought one of his paintings. “I remember looking at it and thinking, ‘Whoever painted that sees the world the way I do.’” Would she ever marry again? “Absolutely.”

Not that Fuller considers her first marriage a failure. Finishing her beer, she smiles. “The only thing is that it didn’t work out the way you were told it was supposed to work out,” she says. “It totally worked out.”