“The courage of the soldier, the courage of the statesman who has to meet storms which can be quelled only by soldierly qualities—this stands higher than any quality called out merely in time of peace.”—Theodore Roosevelt

Today’s presidential candidates don't have to show they’ve proven themselves on a battlefield, but that is new in our history. From Washington to Eisenhower to Kennedy, we as a people have elected war heroes. At the end of the 19th century, Theodore Roosevelt’s exploits under a blistering tropical sun leading a ragtag regiment of Southwestern cowpunchers, Oklahoma Indians, Ivy League football stars, and champion polo players dubbed the Rough Riders made him a bona fide national hero. The 39-year-old bureaucrat, author, hunter, former Badlands rancher, and volunteer colonel was suddenly on the fast track to the presidency.

But to begin, it’s a miracle that Roosevelt even survived Cuba. At the July 1, 1898, Battle of San Juan Heights, he exposed himself time and again to the enemy’s fire. For a good part of the fight, he was the only man in the regiment on horseback (the cavalry division had been forced to leave nearly all of their horses behind in Florida), making him an irresistible target for the Spanish soldiers on the hilltops. They tried their damnedest to knock him out of his saddle but inexplicably failed. Instead, their errant shots wounded and killed Rough Riders who had the misfortune to be standing next to their colonel.

Encouraging his men forward, Roosevelt started a charge on Kettle Hill, a prominence just in front of San Juan Hill. Caught up in the excitement of the moment, African American Buffalo Soldiers and white Regulars from other cavalry regiments joined the Rough Riders in the pell-mell assault. Cheers erupted on all sides. “I most positively assert,” remembered one Rough Rider, “that every face I looked into, both white and black, had a broad grin upon it.”

Just 40 yards from the summit, Roosevelt abandoned his horse at a barbed wire fence and ran alongside his orderly toward a fortified house. Suddenly, two Spanish soldiers jumped out of a trench and fired at the two charging Rough Riders. The distance was no more than ten yards, but the Spaniards missed and then turned to run. Roosevelt, without slowing his pace, instantly raised his revolver and fired once at each enemy soldier. His first shot missed, but the second dropped one of the fleeing Spaniards. An exultant Roosevelt later wrote a friend, “Did I tell you that I killed a Spaniard with my own hand…?”

After taking Kettle Hill, Roosevelt received permission to lead a charge against one of the two blockhouses on San Juan Hill. It was another footrace as Roosevelt and several hundred men ran down Kettle Hill under a withering fire and up the steep slope of San Juan. Between gasps for air, Roosevelt turned to his orderly and shouted, “Holy Godfrey, what fun!” One Rough Rider recalled the charge as “just a mob that went up a hill. If the Spaniards had been able to shoot, we’d never have made it to the top.”

They did make it, but not without heavy casualties. Out of 490 Rough Riders who had entered the battle, Roosevelt reported that he had 86 killed and wounded with a half dozen missing. Almost 40 of his men were prostrated by the stifling heat. As it turned out, the Rough Riders suffered the highest casualty rate of all the cavalry regiments at San Juan, and there was talk of a Medal of Honor for Roosevelt, although some wondered whether he would live to see it. “If there is another battle as hot as the last,” one trooper wrote his parents, “and he exposes himself again as he did then, I look for him to fall.”

There would not be another big battle. The American forces, now in possession of the high ground above Santiago de Cuba, laid siege to the city and the Spanish army holed up there. Sixteen days later, the Spaniards formally capitulated. During the surrender ceremony, Roosevelt gave the command “Present arms!” and his men flawlessly swung their carbines forward in front of their chests in a salute. At the completion of the ceremony, a proud Roosevelt went up and down the line congratulating his Rough Riders. “By George, men, you did that well!” he said, his teeth flashing. “This is a great day in American history—a much greater day than any of us can at the present moment realize.”

But the American army in Cuba still faced another deadly enemy, one they were unprepared and ill equipped to fight: disease. Malaria and yellow fever were the worst. The field hospitals became so overcrowded with fever patients that the surgeons refused to admit any soldier with a temperature of less than 104 degrees.Incredibly, Theodore Roosevelt, who as child had suffered terrifying asthma attacks and other debilitating ailments, remained fit as a fiddle, although he did lose a good 20 pounds because of the heat and poor rations. Concerned about the health of the American forces, Roosevelt lobbied in the press for their return to the States to recuperate, which infuriated the secretary of war and likely cost Roosevelt the Medal of Honor his commanders had recommended for him. (Roosevelt would receive the award posthumously in 2001.)

The United States’ war with Spain ended shortly before the Rough Riders arrived at Montauk Point, New York, in mid-August to a heroes’ welcome, and the regiment was mustered out of the service the next month. But the attention given the Rough Riders and its charismatic leader, media darlings from the very beginning of the conflict, was hardly going away, much to the chagrin of the thousands of Regulars and volunteers who had also fought at San Juan Heights. Judging by all the souvenir paraphernalia, it seemed that Roosevelt and his men had fought the war singlehandedly.

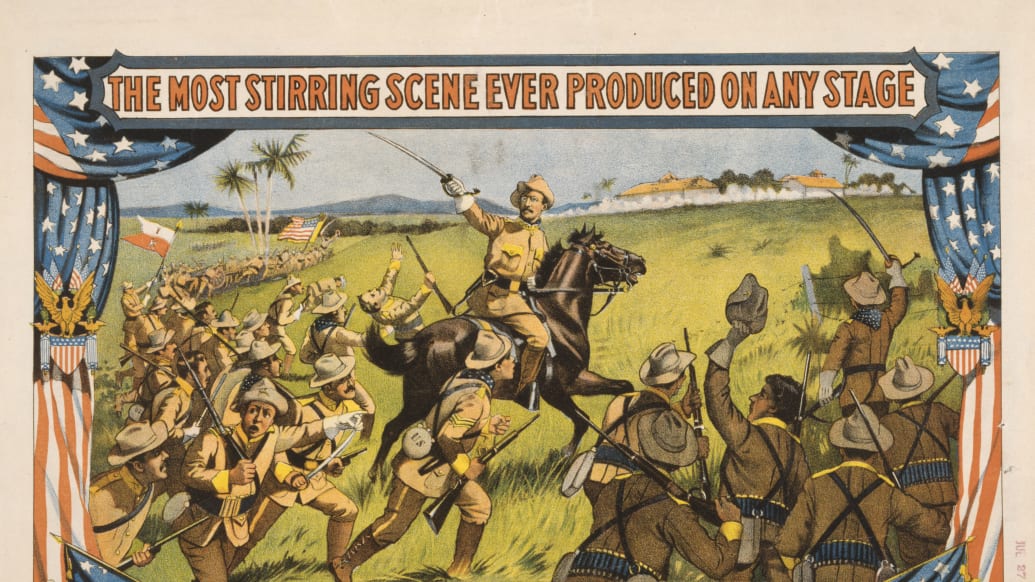

Garish color lithographs and engravings by the score pictured Roosevelt charging up San Juan Hill, artillery shells exploding overhead. Music publishers rushed out sheet music with titles such as “The Charge of the Rough Riders,” and “The Brave Rough Riders.” Children played Rough Rider-themed card and board games. Their fathers smoked Rough Rider-brand cigars while their mothers cooked in the kitchen with Rough Rider Baking Powder. And there were the books on the Rough Riders, including one written by Roosevelt himself, which was a tremendous bestseller.

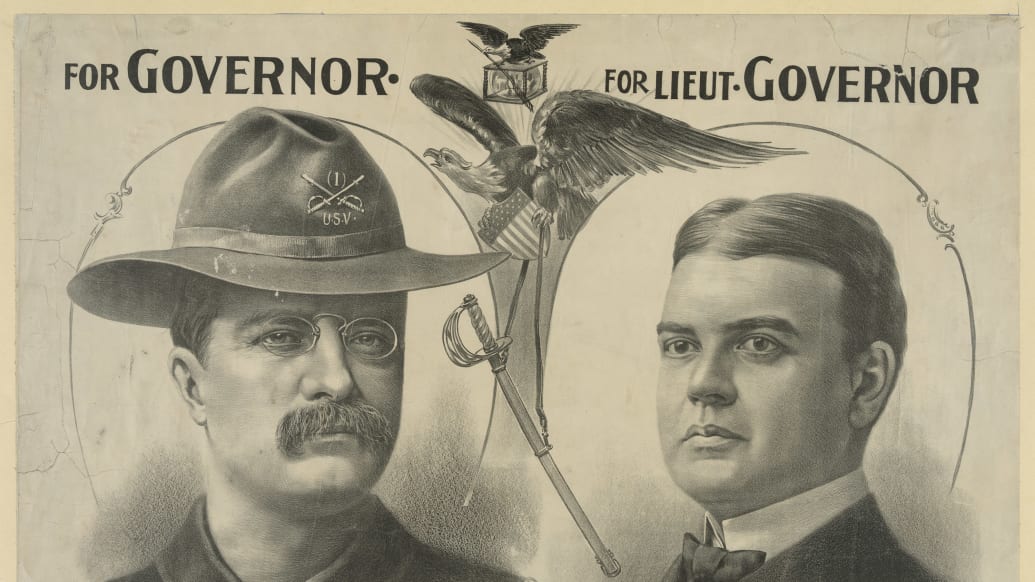

Roosevelt had been suggested as a candidate for governor of New York while he was still in Cuba, and Republican Party bosses lost no time in courting him once he arrived home to Sagamore Hill. Voters sporting campaign buttons picturing Roosevelt wearing his Rough Rider Stetson ushered him into office that November. A year later, with the death of Vice President Garret Hobart, President William McKinley suddenly needed a running mate for the 1900 presidential election. Roosevelt accepted his party’s nomination and was elected with McKinley in a landslide that fall. In September of 1901, however, McKinley was felled by an assassin’s bullet. “That damned cowboy,” as one less-than-charitable politician referred to Roosevelt, was now the president of the United States. Only three years earlier, Roosevelt had stood on the crest of San Juan Hill looking down upon the tiled rooftops of Santiago.

As president, the same qualities that had stirred his men at San Juan also inspired the American people, which is not to say Roosevelt didn’t have his detractors. Divisiveness was as much a part of politics then as it is now, and Roosevelt could be, shall we say, overly assertive. But when he ran for reelection in 1904, he received 56 percent of the popular vote and captured a whopping 336 of 476 electoral votes. He remains today one of our most beloved presidents (and let’s not forget that his 60-foot-tall granite likeness is one of just four on Mount Rushmore). Even President Barack Obama is a “TR” fan.

The National Park Service is this year celebrating its centennial. Roosevelt left office seven years before the NPS was established in August 1916, but no one man did more to shape what our system of national parks, monuments, and other federal lands would become. He created no less than five national parks with a flourish of his presidential pen, and he signed into law the 1906 Antiquities Act, which he then freely used to establish an astounding 18 national monuments during the remainder of his presidency. Several of these monuments were later elevated to national park status, not the least of which was the Grand Canyon.

In addition to these presidential acts, Roosevelt was able to instill in many Americans the hearty respect, passion, and love he had for the country’s natural and historical wonders. In a justly-acclaimed speech at the Grand Canyon in 1903, he remarked, “We have gotten past the stage, my fellow citizens, when we are to be pardoned if we treat any of our country as something to be skinned for two or three years for the use of the present generation, whether it is the forest, the water, the scenery. Whatever it is, handle it so that your children’s children will get the benefit of it.”

Not all of our presidents fulfilled the promise they had shown as leaders on the battlefield (see U.S. Grant), but there is no question Theodore Roosevelt did. His conservation efforts are just one example of his many accomplishments, which are surely daunting to all those who take up residency in the White House. But Roosevelt’s accomplishments, like the open skies and wondrous vistas of our national parks he helped save, should continue to serve as inspiration also. Our children’s children will be the better for it.

Mark Lee Gardner is an award-winning author and historian whose latest book, Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment, and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill, was recently released by William Morrow/HarperCollins.