The year is 2050. You’re prepping the house for another chaotic Thanksgiving with your kids, in-laws, aunts, uncles, cousins, and even a few friends. As you run through the recipe list for the big day, your heart jumps into your throat when it occurs to you: You forgot to buy the turkey.

But, the worry quickly dissipates and you roll your eyes at your own forgetfulness. After all, that’s not something you have to worry about anymore. In fact, no one has to worry about running out to grab a frozen bird from the grocery store—not since we started making turkey meat in factories.

That’s not just a sci-fi vision of a far-flung future either. The cultivated meat industry (also known as lab-grown meat) continues to grow as the world comes to terms with the public health, climate, and ethical consequences of eating animals. Companies like Upside Foods, Wild Type, Finless Foods, and Meatable have been developing and producing chicken, seafood, beef, and pork all from a laboratory.

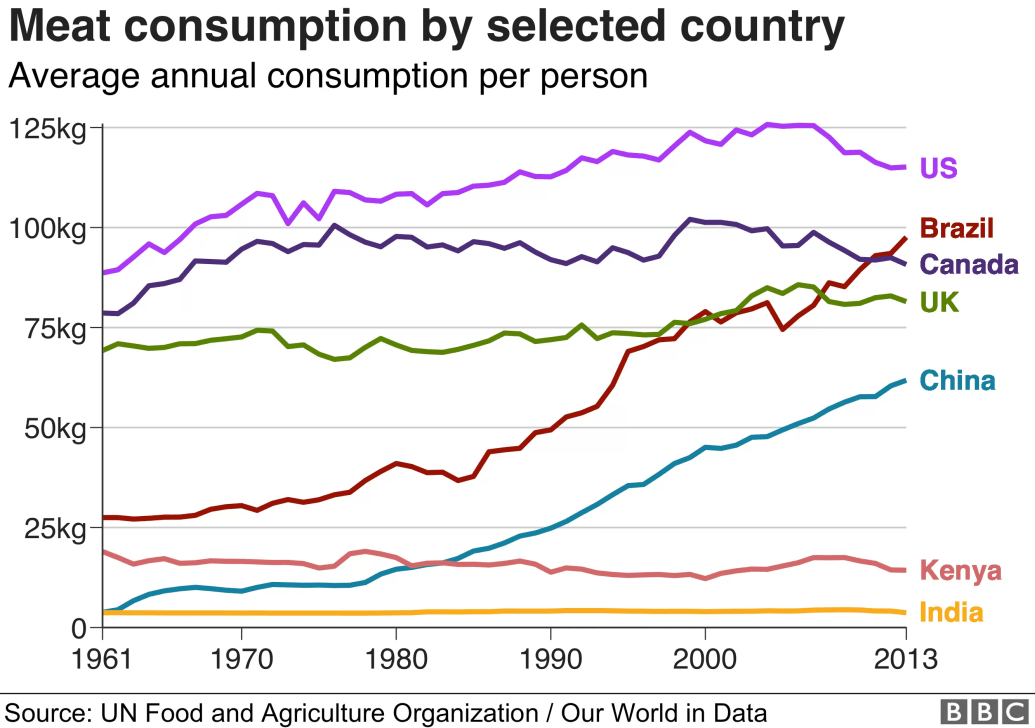

While it’s easy to brush it off as a flash-in-the-pan food trend, the rise of lab-grown meat is going to happen whether you like it or not. Developed nations consume the most meat overall. As more countries around the world grow and get richer, meat consumption is expected to rise with it.

And there are also environmental factors driving the development of lab grown meat too. Livestock production accounts for nearly 15 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, making it one of the primary contributors to global warming. One day, we might not have very much of a choice but to cut back from our meat eating habits.

“I think it's an inevitability,” Paul Mozdziak, a poultry scientist at NC State University, told The Daily Beast. For him, it’s not so much a question of if lab-grown meat will hit supermarket shelves on a wide scale, but when. “Is it gonna be in the next six months, or the next six years, or the next 50 years? I don’t know. That’s a great mystery.”

Courtesy of the BBC

Mozdziak has dedicated his career to researching the best ways to create lab-grown poultry—which can be replicated easier than beef or pork, he said. And there are actually a few different ways to create test tube meat, but it all boils down to getting cells from the actual animals and reproducing them in a lab.

The cells that Mozdziak has found success with in the past are called satellite cell platforms, which are stem cells that help repair your muscle if it gets injured. You can take these satellite cells from, say, a turkey and inject them into a cell culture in a Petri dish or test tube. Then these cells start to grow into brand new muscle cells and voila, you have lab-grown meat to feast on… kind of.

Cultivated meat often lacks a vital quality that sets normal meat from the test tube stuff: structure. Think about the specific texture that comes with a chicken breast or a good cut of steak. It’s chewy and distinct. Unfortunately, cultivated meat doesn’t necessarily come that way right out of the gate. Instead, much of the lab-grown variety grows like a mushy slurry a bit like ground beef or even soft-serve ice cream—which obviously isn’t the most appetizing thing out there.

Nuggets made from lab-grown chicken meat are seen during a media presentation in Singapore.

NICHOLAS YEO via Getty

However, there are workarounds. You can cook some of the meat as is à la sloppy joes or chorizo. But researchers are also working on creating “scaffolding” to help give the cultivated meat structure. For example, Harvard University scientists published a 2019 study in the journal Science of Food where they used gelatin to create scaffold fibers to recreate more familiar meaty textures.

That brings us to our future Thanksgiving centerpiece: test tube turkey. Based on his experience and research, Mozdziak said that the turkey satellite cell platform—which is one of the ways in order to create the alt-meat—is one of the best for creating meat. In fact, poultry as a whole offers a much easier way to replicate than beef or pork due to how much easier the cells are to control and because there’s less of a chance of contamination.

“I believe the avian meat is easier,” Mozdziak explained. “I get less contaminating cells that don’t form muscle, and the cells more easily differentiate in my hands than mammalian systems.”

Unfortunately, even though there is a relatively big market for cultivated chicken, the same can’t be said for Tom Turkey. Perhaps the biggest (and only) player interested in cornering the faux-turkey market is Blue Ridge Bantam from Whitesburg, Tennessee, which has consulted with Mozdziak regarding the in-vitro meat process in the past. The company has yet to put a product out to market.

Upside Food's first commercial product is going to be a chicken filet—with the potential of turkey in the far off future.

Courtesy of Upside Foods

Upside Foods, a much bigger startup in the alt-meat world, hinted that it would explore creating a whole turkey “if the demand is there,” a spokesperson told TechCrunch in 2016. Apparently, however, there hasn’t been much interest in the past six years; the company hasn’t worked on developing a turkey product (let alone an entire turkey) since then, primarily showcasing its alt-chicken product instead.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll never make turkey. “The first product we commercialize will be a chicken filet, but we are working on a variety of other products,” David Kay, the director of communications at Upside Foods, told The Daily Beast. “Ultimately, we are interested in producing all commonly consumed types of meat, including turkey.”

But even if there was more interest from consumers, the alt-meat industry has their work cut out for them in order to finally bring their product to the masses. Even though costs have fallen dramatically since cultivated meat came onto the scene (a single lab-grown burger cost $330,000 in 2013), these products will still be more expensive than the real thing, since there’s no current infrastructure to cultivate fake meat at a large scale akin to the livestock industry.

Moreover, alt-meat companies have consistently run into the maddening wall of bureaucracy. Upside Foods became the first cultivated meat company to receive FDA approval for its chicken filet product just this month. Even after clearing that hurdle, the company still need USDA approval in order to sell it to customers.

“With this evaluation by the FDA complete, we can now rapidly complete the remaining work of obtaining our grant of inspection and label—all of which is well under way,” Kay said. “Once we complete the remaining USDA steps, we will start commercial production and sales.”

On top of all that, there’s also competition in the alt-meat market from plant-based offerings like Beyond Meat. These companies could be viewed as holding an ethical high ground since they don’t need to obtain cells from livestock the way that cultivated meat does.

Of course, which fake meat option consumers choose will almost certainly come down to which one tastes the most like the genuine article—and that’s where cultivated meat might win out in the end.

But, like Mozdziak said, these are merely hurdles on the way to the inevitable. Companies like Upside Foods have even received funding and support from the likes of conventional food conglomerates like Tyson and Whole Foods, signaling that cultivated meat has the interest of traditional meat and grocery industries.

“It’s going to be really hard [to bring this to market], it’s going to take a long time, and it’s going to cost a lot of money, but we’re eventually going to get there,” Mozdziak said. “It’s possible to get something out in the market, but to get to the masses, it’s going to take some time. But are we gonna get there? Absolutely.”

So, while you’re carving into a juicy turkey this Thanksgiving, be sure to savor every moment. It might be one of the last ones you’ll eat—at least, one that didn’t come from a test tube.