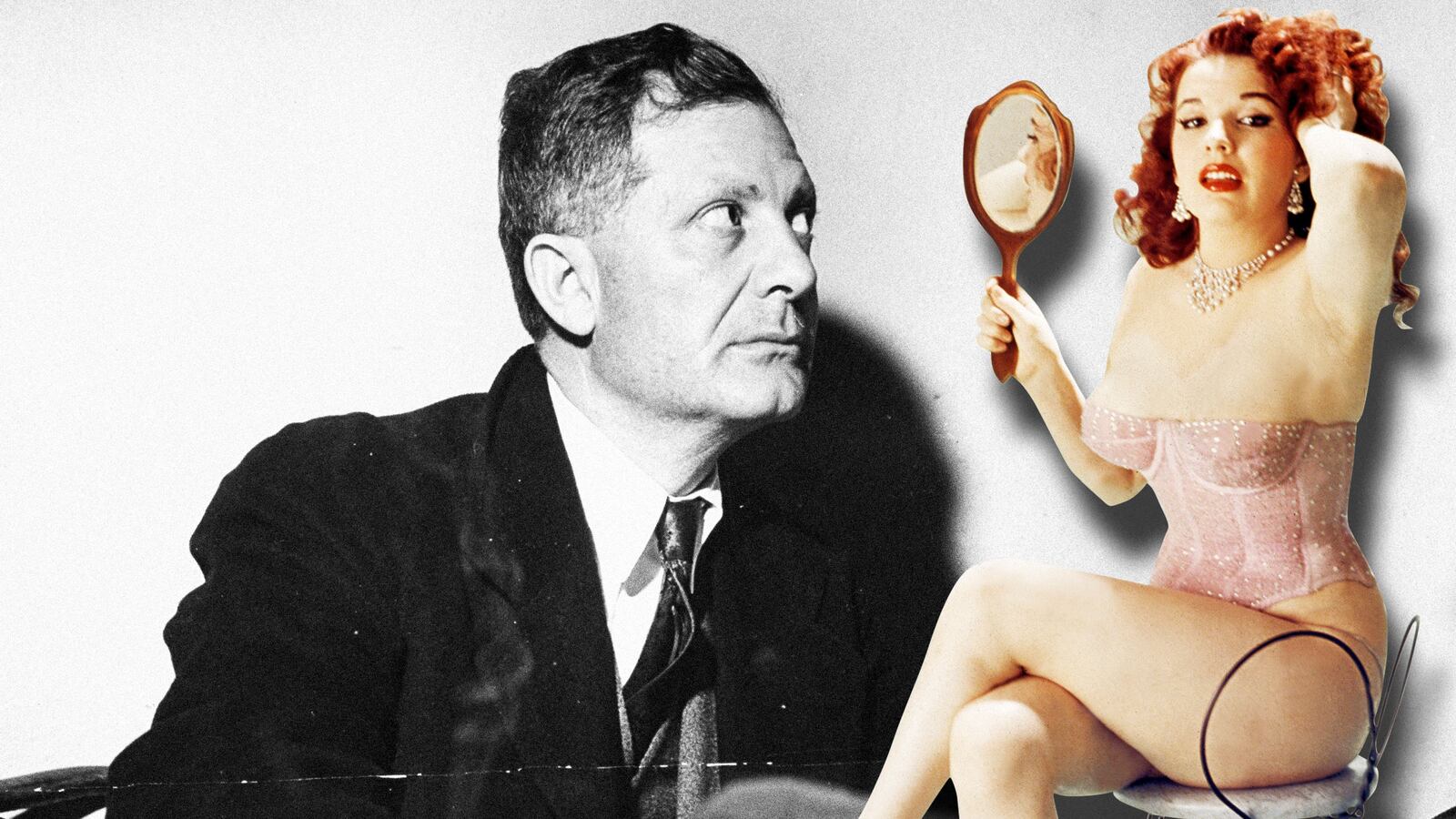

Heard the one about the stripper and the politician? No, not that one.

Long before Donald Trump ever set his sights on Stormy Daniels from across a golf course, the nation collectively leered at the affair of Louisiana Gov. “Uncle” Earl Long and Baltimore burlesque queen Blaze Starr, aka “Miss Spontaneous Combustion.”

In 1959, Earl K. Long was in his third term as governor and planning to run for a fourth by circumventing a law against consecutive terms. He was popular, especially among poor whites and blacks, and he’d worked hard at politicking to emerge from the jowly shadow of his older and more famous late brother Huey.

Long bore little resemblance to Trump in policy: he taxed oil and gas companies to pay for new roads, bought textbooks and hot lunches for school kids, built universities, and worked to enfranchise thousands of black voters in Louisiana (cynical vote-hunting, but unique among southern politicians of the day.) He was, however, notorious for his eccentricity, his ability to exploit loopholes, his rewarding of loyalty, his foul language, his aggressiveness with women, and his knack for patronage (a reporter asked him how many people worked in the capitol building and the governor replied, “about half of them.”)

The FBI kept an open file on his ties to mobsters and he had a combative relationship with the press, blasting the “lying newspapers” for being unfair to him while manically courting them for publicity. He called the Times-Picayune the “Times Pick-on-you,” and once invited friends over to watch him spit on a newspaper. For graft he was legendary. One friend recalled Long lying in his underwear on a couch in the Roosevelt Hotel; for hours politicians, pimps, bookies, and lobbyists walked in and dropped wads of cash onto the prone governor. When it was over he said, “I’ll bet that’s the most expensive suit of clothes you ever saw.”

Long loved a good striptease, and frequently caroused the fleshpots of Bourbon Street when he needed rest from pumping hands and pocketing cash. This election was his toughest yet, and he was keeping long hours, fueling his 63-year-old body with fried steaks, Coca-Cola, whiskey, cigarettes, and Dexedrine. Seeking respite one January night, the governor and his bodyguards stopped at the Sho-Bar on Bourbon to see the new girl.

Blaze Starr was the most famous exotic dancer in America, partly thanks to an Esquire profile, but also thanks to her bouffant of red hair and her size 38DD breasts. One journalist remarked that “her face, sandwiched between her hair and bosom, is sometimes missing.” She was—with the possible exception of Gypsy Rose Lee—the first nationally famous adult entertainer in America. She was a local institution in Baltimore, where Johns Hopkins fraternity pledges had to ask her her measurements as part of their initiation. Starr was a hard-working woman, earning her reputation as a first-class performer with her wit and sensational stage shows. In one act, she trained a panther to peel off her clothes by attaching pieces of steak to the straps. In her signature bit, she built a mechanical chaise lounge on which she’d bump and grind. At the climax, she’d lay back and flip a switch: lights flashed, a fan blew red streamers, and smoke erupted from between her legs.

That night at the Sho-Bar, while performing the couch routine, a man in a suit and some police officers walked in and sat down at a table. Starr had been arrested for indecency before, recently in Philadelphia, where she’d wiggled her way out of trouble by seducing Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo, who’d had an eye on her ever since her panther had escaped her hotel room.

But this time there was no arrest. Backstage the manager told her that the governor wanted to meet her. She didn’t believe him, but soon she was sitting and having a drink with Earl Long, governor of Louisiana. The two immediately hit it off, bonding over their country roots. Starr was raised in an Appalachian hollow in West Virginia where her twelve-toed grandpa made moonshine, the folks played clawhammer banjo, and the local recreation was plugging your neighbor full of buckshot if he broke the commandments about coveting your wife or livestock. The Longs came from Winn Parish, Louisiana, where Earl occasionally returned to his “pea patch” farm to slaughter hogs, eat huckleberry pie, and otherwise commune with nature.

Both were born fighters. Starr survived violent assaults from other strippers and multiple rape attempts. Long had spent a lifetime in some of the dirtiest and hardest-fought political campaigns in the country, coming to blows with opponents on no fewer than nine recorded occasions. Starr was going through a divorce and separation from her husband, who couldn’t take the strain of her touring. Long and his wife “Miz” Blanche were increasingly estranged, with her worried about his erratic and self-destructive behavior.

Starr says they fell in love, claiming in her autobiography that Long proposed to her, showing her a fake ring in case she said no and then pulling out a bigger one when she said yes. However, the words “a novel” were quietly added to the cover of the book’s paperback edition, possibly to prevent legal action for implying that Blanche Long was poisoning her husband’s food. Blanche and others later insisted that his affair with Starr didn’t meant anything, but Starr maintained that it was a passionate romance, with her dining in his hotel suite, and him visiting her frequently during his campaign to make love and talk in confidence.

She says that the two went picnicking in the swamps, and that he occasionally brought her to the rural stump speeches he gave in which he’d unfailingly show up late, having stopped to buy enormous quantities of hams, potatoes, alarm clocks, earthworms, candy and cigarettes which he distributed to the crowds. Earl would mount the stage, remove his shiny mohair suit jacket, roll up his sleeves, and speak extemporaneously, snapping his red suspenders, telling earthy jokes, hollering about the plight of the common man, occasionally dousing a handkerchief in Coca-Cola and mopping his sweaty brow with it, and demonstrating his facility for insulting his opponents, using nicknames like “Slippery Sandlin,” calling one “smooth as a peeled onion,” and saying of another: “that man is a confirmed alcoholic. He’s a wife-beater… and,” he added for good measure, “he has diabetes.”

Long may have needed Starr’s affection. In addition to tensions between him and his wife and being investigated by the IRS (“I’m the most investigated man in history”), Long was fighting a tough campaign. Long was just as racist as the next chap, but he knew segregation would end—he just wanted it to go peacefully. In private he spoke southern treason: that the Civil War was a mistake and Abraham Lincoln was right. In public, he was a staunch segregationist, denouncing both white supremacists and the NAACP as equally radical rabble-rousers—hatred and bigotry on many sides. His opponents cited his popularity among blacks and his opposition to purging black voters from the rolls. This was no subtle dog-whistling: One rival said “don’t wait for your daughter to be raped by these Congolese.”

Worn out, paranoid, mastered by booze and speed, Long lashed out, delivering a raging, profanity-laced speech to the legislature. He was rambling, semi-coherent, and furious, mouthing an infamous phrase to an opponent wearing a Confederate flag necktie, perfectly expressing Long’s untenable middle path: “niggers is human beings!” The next day his office prepared an apology which he promptly threw on the ground before bursting into another accusatory tirade, sweating and pausing only to guzzle vodka and grape juice from a Coke bottle.

Following these outbursts Blanche, already furious about Long’s affair with Starr, had him forcibly committed to a mental institution in Texas, where he told a reporter that “there never has been a man brutalized and handled—governor or no governor—like I’ve been handled.” He was released after threatening to charge his wife with kidnapping, but once brought home with the promise of freedom, he was thrown, violently fighting, into another asylum. When Long told a fellow patient he was the governor of Louisiana, the man replied, “I used to think I was Dwight Eisenhower.” The hospital director introduced himself as Dr. Belcher. Long replied: “The hell you are. You were Dr. Belcher.”

Long made good on the threat. In a cunning maneuver, he fired the director of the state hospital board and replaced him with an ally who in turn fired Dr. Belcher and replaced him with a loyal puppet who immediately had Long released. One of his first visitors was Blaze Starr, who ran from her car to his motel hiding her face with a handkerchief.

The damage to Long’s reputation was extensive. Newspapers and magazines played up the mad hillbilly. Blanche betrayed him further by recounting the episode for Life, published under the headline: “A Portrait of Earl Long at Peak of Crack Up.” When Earl was told that she’d received $5,000 for the article, he opined that he should get half. Time wrote: “The fact was clear: Earl Long had just gone plain crazy.” Long hit them with a $6 million libel suit.

Rather than rest, Long decided to continue his campaign after a madcap vacation, bringing along several friends and a psychiatrist, to prove he wasn’t sick. Starr claimed that he invited her, but that she declined for appearance’s sake. He lost thousands of dollars at racetracks throughout the Southwest, visited Mexican brothels, and bought cowboy boots by the score. He ate and drank until he began to regain the weight he’d lost, and he tried to discourage the paparazzi by wearing a pillowcase with eyeholes over his face. None of this helped his “I’m not crazy” case, but it made for great copy.

Long returned to Louisiana and lost the election. Starr said he threw one last party at the Governor’s Mansion with her and other strippers who got naked, drank champagne, and packed up the china. He and Blaze stole the show at the inauguration of Long’s successor: she stunning in an uncharacteristically demure lace hat and candy-striped pussy-bow blouse, him looking undefeated, shaking hands, joking, and hogging the spotlight. The two took turns filming each other with a portable movie camera.

Long immediately threw his hat into a House race, and Starr went home to Baltimore as he began another grueling campaign. The “Committee to Save Louisiana from National Embarrassment” ran ads featuring Starr and Long with the pillowcase on his head. On election day Long was in bed with severe chest pains, refusing to get help, fearing that news of him in the hospital would scare off voters. He won, and ten days later he died. Among the mourners at his funeral was a beautiful redhead who paid her last respects by pulling a single red rose from her ample cleavage and placing it in the casket. As A.J. Liebling of The New Yorker noted: “she had been on his side when a lot of the political mourners weren’t.”

Blaze Starr was an ambitious woman, and the affair was fuel for her fame. She made no secret of this, dancing for audiences who came to “see what the governor saw.” When one woman heckled her with “How did old Earl look laid out in his casket?” Blaze’s two sisters—also strippers—dragged the woman from the bar and thrashed her. Starr wrote her autobiography, unashamedly cashing in on the story of her sensational affair, and it was ultimately turned into a highly-fictionalized movie, Blaze, starring Paul Newman as an implausibly handsome Earl Long. Starr also bought and ran the 2 O’Clock Club in Baltimore where she remained the star attraction well after the rest of the clubs had gone to seed.

Blaze Starr died on June 15, 2015, one day before Donald Trump declared his presidential candidacy. The Advocate in Baton Rouge wrote: “Blaze Starr…should best be remembered for pioneering what’s now become a celebrated American art form: the use of scandal for fun and profit.” It’s true that Starr capitalized on her affairs—she claimed to have once had a quickie with JFK in a closet and would have gone a second round with him in 1962 if the Cuban Missile crisis hadn’t interrupted them—but to her there was no scandal, and besides, her dear Uncle Earl was never shy of a little publicity.