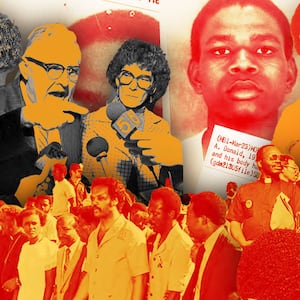

There are two tragedies in The People v. the Klan, CNN’s four-part docuseries premiering on Sunday, April 11. The first is the brutal lynching of 19-year-old Black teen Michael Donald on March 21, 1981, which shattered his family in Mobile, Alabama, and went unsolved for more than 18 months, until it was finally determined that the Ku Klux Klan had been behind it. The second is the fact that this crime didn’t occur in a vacuum but, rather, was part of a long legacy of racial terror—especially in the American south—which continues today in metastasized form, as evidenced by the recent killings of, among others, Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

Produced by horror maestro Jason Blum and directed by Donnie Eichar, The People v. the Klan is a story about a fight for justice that resulted in triumph, and at its center is Beulah Mae Donald, Michael’s courageous mother.

On the evening of March 20, 1981, Michael left the family home to buy a pack of cigarettes at a nearby gas station. When he didn’t return home, his mom and siblings—including sister Cecelia Perry, who speaks candidly and at length in the docuseries—became concerned. Their worst fears were realized the following morning, when news arrived that Michael had been found hanging from a tree on Herndon Ave., his body badly beaten and his throat slit. The discovery of his wallet helped police identify him, and three suspects were quickly arrested. Yet when it became clear that they had been wrongly accused, the investigation ground to a halt, much to Beulah Mae and company’s chagrin.

Their frustration, anger and anguish was exacerbated by the context in which Michael’s murder had taken place. The police had deep, enduring ties to the Klan, and the detective in charge, Wilbur Williams, had been peripherally involved in a prior 1976 incident involving a number of cops detaining Glenn Diamond in order to beat him and hang him by a noose—albeit not fatally, since they claimed it was a “prank.” Furthermore, Mobile had just hosted the headline-making trial of Josephus Anderson, a Black man accused of killing a white police officer in Birmingham, which ended in a mistrial. And of course, there was the lengthy history of racist murder throughout the South, most infamously of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old boy lynched in Mississippi in 1955, as well as of four young girls who perished in the 1963 bombing of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church.

The fifth victim of that bombing, survivor Sarah Collins Rudolph, participates in The People v. the Klan, as do a host of talking heads, including former Mobile Mayor Sam Jones, district attorney Chris Galanos, former NAACP President and current Harvard Kennedy School professor Cornell William Brooks, and then-U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama Jeff Sessions, who confidently states, “I wanted the African American community to know that the United States Attorney’s Office in Mobile, Alabama, was not going to back away from tough civil rights cases.” Let’s just say that many others weren’t as convinced of Sessions’ dedication, especially attorneys Michael and Thomas Figures, the latter of whom later testified before Congress (when Sessions was nominated for a federal judgeship in the 1980s) that Sessions had initially attempted to dissuade him from taking Michael Donald’s case.

Sessions denies such accusations with offputtingly cheery bluntness, claiming, “I tell the truth, and someone else can write the history.” The real focus of The People v. the Klan, however, is the many men and women who wouldn’t let Michael’s killers get away. Thanks to the efforts of Michael and Thomas Figures, Galanos, FBI special agent James Bodman, investigator Bob Eddy, attorney Doug Jones and more, the cops’ original theory that Michael’s death was drug-related was exposed as a sham. Instead, Bodman learned that the street where Michael had been hung was home to numerous members of the KKK. Chief among them was Bennie Jack Hays, the second-highest-ranking Klansman in Alabama, and a nasty old racist who can be seen walking by Michael’s still-hanging body in a shocking archival clip and who in separate footage attacks a news cameraman outside a courthouse.

As with many television docs, The People v. the Klan likely could have handled this material in three episodes. And the greater saga of American racial hostility and unrest is a topic that requires more time and care than Eichar can grant it. Nonetheless, his series lucidly lays out the means by which Michael’s crusaders uncovered the plot to kill Michael, which was ordered by Hays and carried out by both his son Henry (who always sought his domineering father’s approval) and 17-year-old James “Tiger” Knowles. A new interview with Knowles, who flipped on his compatriots, is shot in darkness, as is one with his Klan buddy Frank Cox. Their input, as well as commentary from their picked-on Klan cohort Teddy Kyzar, helps provide a comprehensive overview of this heinous nightmare, revealing that Michael was selected at random during a hunt for a Black person to kill as payback for Anderson evading conviction.

For refusing to simply accept Michael’s execution as par for the Alabama course, for demanding an open casket at her son’s funeral (as was done for Till), and for eventually going after the United Klans of America organization in a civil trial (aided by Morris Dees’ Southern Poverty Law Center) that saddled the hate group with a crippling $7 million penalty, Beulah Mae Donald is venerated in The People v. the Klan as a member of a long line of Black mothers forced to seek justice for their slain sons. In doing so, the series highlights the sad familiarity of this story, both then and now, given that tales of woe like Michael’s have been far too common in America, including in this present moment. In his closing argument at the civil trial, future senator Michael Figures said that the judge had to send a message, or we’d never escape the question, “Who will it be tomorrow?” As Eichar’s history lesson elucidates, it’s something we’re unfortunately still asking today.