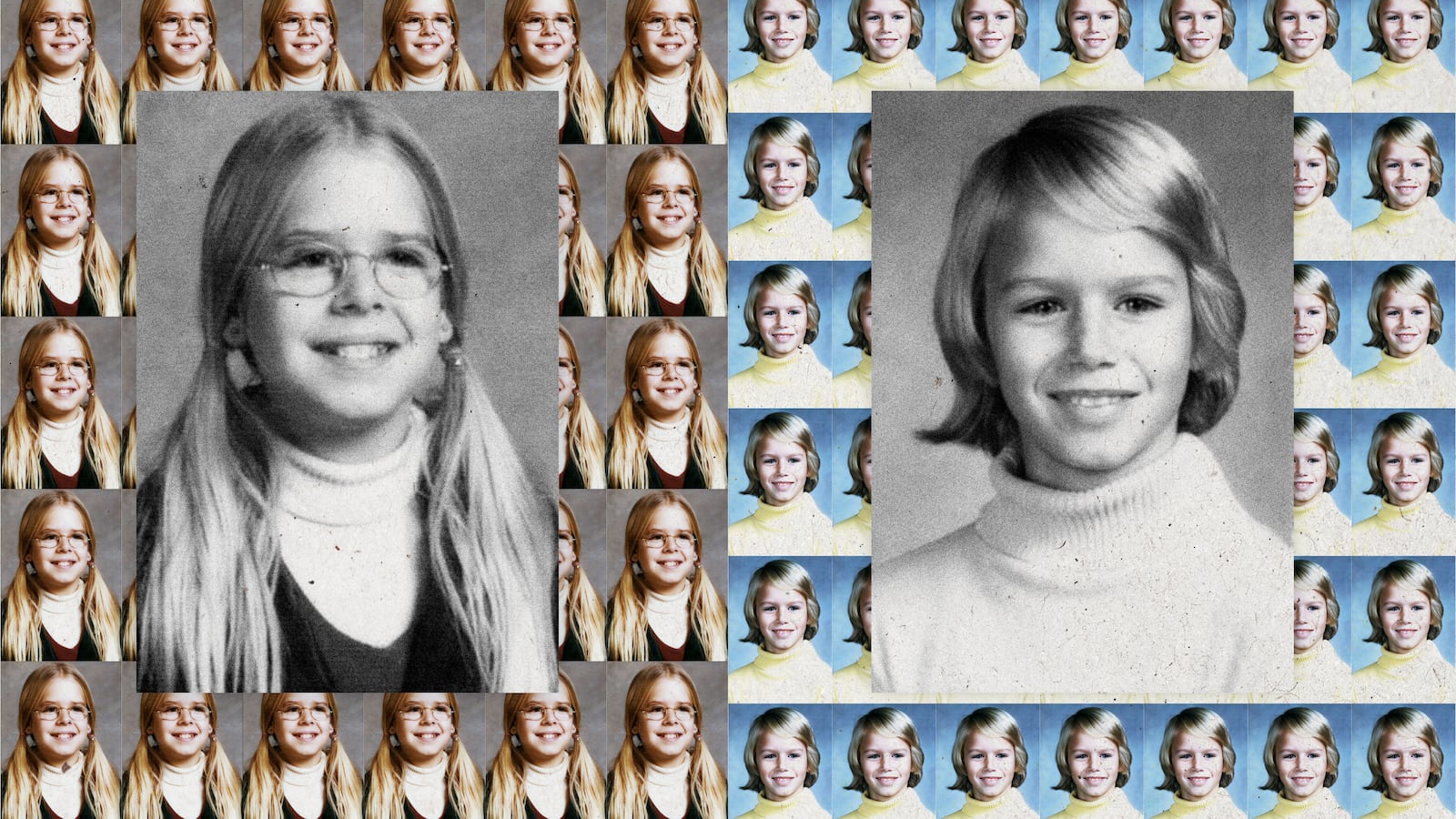

One was in fifth grade, the other seventh. Katherine Lyon and her older sister Sheila made the honor roll, kept spare change in piggy banks, and tacked posters of Kenny Loggins and John Denver to their bedroom walls. In the last week of March 1975, they vanished from a mall in Wheaton, Maryland, just north of Washington. Their disappearance transfixed the public and puzzled police. Weeks passed, and as it grew less likely that their daughters would be coming home, John and Mary Lyon grieved and wondered.

John Lyon hugs his wife, Mary, right, after a plea by Lloyd Lee Welch Jr., for the killings of their daughters Sheila and Katherine Lyon in 1975, in Bedford County Circuit Court in Bedford, Va.

AP/REX/ShutterstockMark Bowden, a rookie reporter with the Baltimore News-American, spent much of that spring writing about the missing Lyon girls. When the investigation came to a standstill, he and his colleagues moved on to the next story. He’s since published several nonfiction bestsellers, including Black Hawk Down and Hue 1968. The Lyon story has always bugged him, though. In 2015, the case resurfaced in the pages of the Washington Post, which reported that investigators in Maryland appeared to be closing in on a culprit. Bowden felt compelled to find out what was going on. “A story like that doesn’t really ever leave you,” he told me in a recent interview.

The result of his curiosity is The Last Stone, a gripping new book that seeks to differentiate itself amidst a surplus of true-crime titles, documentaries, and podcasts. Drawing on a deep cache of question-and-answer sessions between Montgomery County, Maryland. police and one of their chief suspects in the girls’ disappearance, Bowden gives us an eerily intimate look at what it can take to crack a cold case. It’s not the first time he has written about the interrogation of reputed criminals and terrorists. This time, though, he had access to dozens of hours of videotaped conversations.

Cold cases, Bowden writes, are often “defined by wasted effort,” as police duplicate the work of their predecessors, “pursuing leads so unpromising that others had long ago abandoned them.” Indeed, in the Lyon investigation, there was a notable lack of physical evidence. This meant that if officers were going to make an arrest, they’d have to get their information by repeatedly buttonholing witnesses and suspects—which is what they did with a convicted sex offender named Lloyd Welch.

Left, Montgomery County Police mugshot of Lloyd Welch in 1977 after Welch was arrested for a residential burglary near Wheaton Plaza. Right, Lloyd Lee Welch

Montgomery County Police Department; Bedford County Sheriff's OfficeOn April 1, 1975, less than a week after Katherine and Sheila Lyon were reported missing, Welch, 18, went to the mall where they were last spotted. He told a security guard, and then a police officer, that he’d seen the girls leaving with a sketchy older man. His story included strange details—he had a lot to say about the pinstripes on the car the girls purportedly rode away in—but ultimately, it was written off as unconvincing. The cops figured Welch was just trying to collect some reward money. A summary of his statement was set aside, Bowden writes, and Welch’s link to the case was forgotten. Decades passed.

In the 2010s, a Montgomery County officer, hunting for overlooked clues in the Lyon case, came across Welch’s report. Why hadn’t this guy—now nearing 60 and locked up for sexually assaulting a 10-year-old girl in Delaware—received more scrutiny? Shouldn’t they talk to him now, better late than never? So began a grim pas-de-deux, in which Det. Dave Davis met with Welch for a series of subtle, increasingly revelatory interviews.

The transcripts of these sessions, which make up much of the book, serve as a case study in the effectiveness of the Good Cop method of interrogation. Davis, often accompanied by colleagues, met with Welch 10 times over a year-plus, plying him with fast food, praising his intelligence, and feigning anger on his behalf when Welch claimed that he was being persecuted. Welch’s story constantly evolved. At first, he said he knew nothing. Later, he conceded that he talked to the girls, after which he admitted that he saw them being raped. In time, the officers “teased out the whole abomination,” Bowden writes, and in September 2017, he pleaded guilty to murdering Katherine and Sheila. Welch will never get out of prison.

Though he thought he was done with the Lyon story, Bowden says he decided to return to it after an informal chat with a new generation of officers tasked with solving the case. “They explained to me that the whole case rested upon this marathon interrogation of this guy,” he says. “I said, Do you have transcripts? And they said, No, we have video. I thought, Oh man, I’m going to have to look at all this.”

Bowden presents compassionate portraits of the victims, telling us about the girls’ respective personalities, what they did for hobbies and chores, how they decorated their rooms. But he can’t be accused of writing an opportunistic tearjerker. His interest, he says, “was primarily in the way that the case was solved.” Talking to Davis and other officers, “it was clear they had no physical evidence of any consequence. They had no witnesses other than, as it turned out at the end, a couple witnesses possibly seeing the bodies burned. The bulk of the case, from beginning to end, rested on these conversations with Lloyd Welch. I zeroed in on those because that’s where the work was done.”

Even some of the genre’s biggest devotees will admit that there’s a glut of true-crime content. We’re in an era of four-part documentaries inspired by 12-part podcast series. Bowden is aware of this overabundance, and he doesn’t want to add to it (a portion of the book’s proceeds will be donated to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. He wouldn’t “have gone back to write a book about the Lyon sisters and their disappearance,” he says, if he felt like he was just rehashing “the tragedy of it and the mystery of it… For me, that wouldn’t have been enough.” He needed a different angle. “The moment when I decided that I was going to start looking at it seriously, potentially as something book-like, was when I found out there was” so much interrogation video—about 70 hours.

On top of that, there were many hours of audio. It took months for Bowden to make sense of it all. “I remember my wife telling me how sick of hearing Lloyd Welch’s voice she was,” he says, “because I’d be sitting there with my laptop, watching hour after hour of interrogations.” Bowden’s patience, his willingness to listen to a monster tell his story, has yielded an unusual, compelling book, a worthy effort in a crowded field.