The late middle ages in western Europe were dominated by the Hundred Years War, which raged between England, France, and their various allies (including Castile, Navarre, Burgundy, Flanders, and the city states of northern Italy) from 1337 until 1453. They included many famous land battles—Crecy, Poitiers and Agincourt among them—but what is less well known is that some of the most vicious fighting took place at sea.

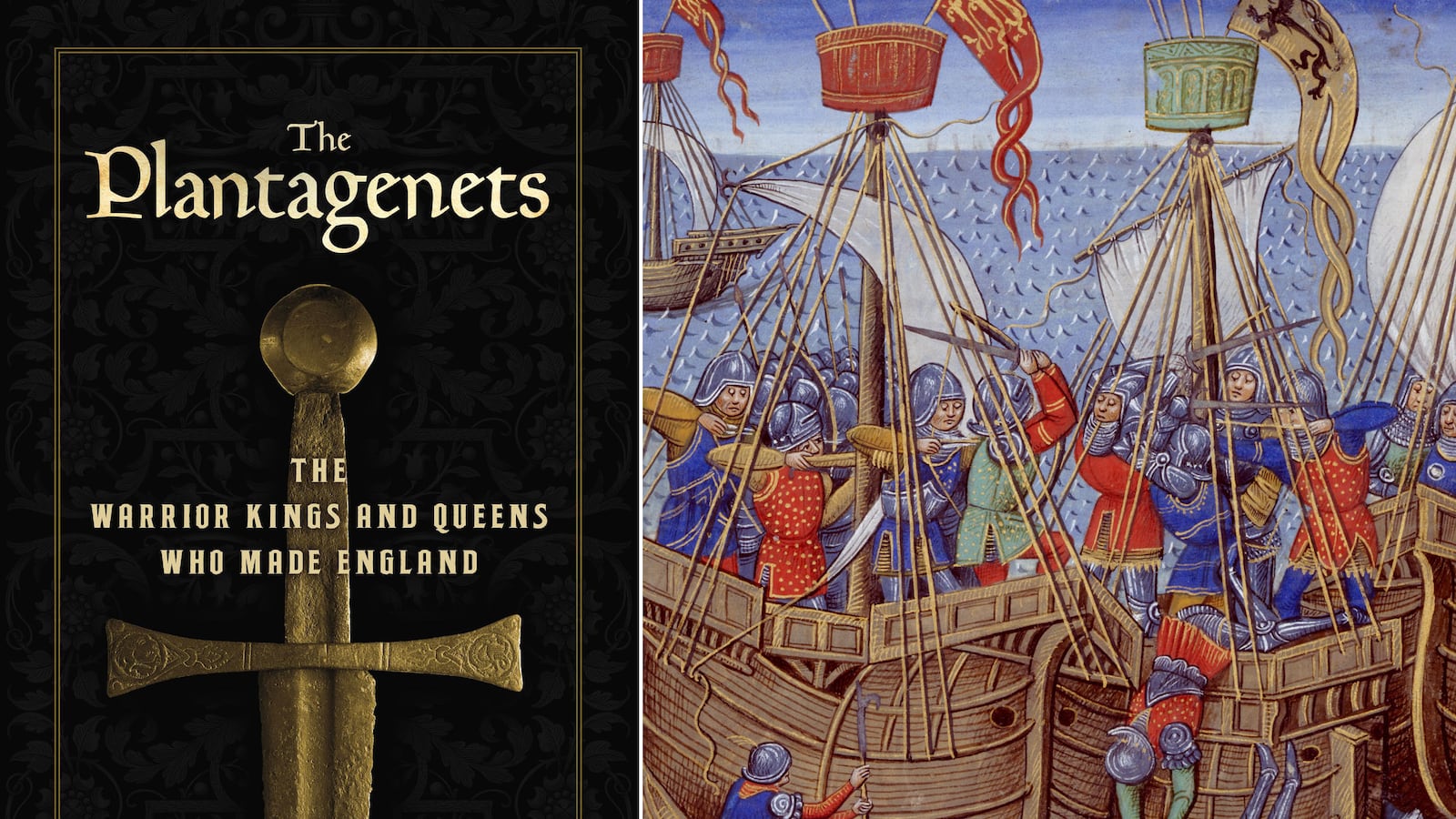

The battle of Sluys in 1340 was one of the first serious engagements of the war, when English ships under King Edward III attacked the French fleet of Philip VI off the coast of Flanders (today a part of Belgium). It is described in this excerpt from historian Dan Jones’ new book, The Plantagenets: The Warrior Kings And Queens Who Made England.

Readers may notice a similarity between the battle of Sluys and a more famous sea engagement: The Battle of Blackwater, the crowning moment of season two of Game of Thrones. Where do they get this stuff from? Well, now you know.

Edward at Sea

As dusk approached on the evening of June 24, 1340, six months after he had declared himself king of France as well as England, Edward III stood aboard his flagship, the cog Thomas, a large merchant-style vessel with a single square sail, and watched the sea off shore from Sluys, in Flanders, churn with the blood of tens of thousands of Frenchmen. He was wounded in the leg, but the injury was worth the pain. A fierce battle raged before him between the 213 French and Genoese ships of Philip VI’s Great Army of the Sea and around 120 and 160 English sails, which had left East Anglia under Edward’s personal command two days previously. The English were murderously, brilliantly winning.

Edward had crossed the Channel to put an army ashore in Flanders. It was a desperate action dictated by extreme circumstance. Two months earlier his friends and allies the earls of Salisbury and Suffolk had been captured while fighting outside the town of Lille. Flanders was overrun by the French, and Queen Philippa had been taken hostage in Ghent. The Channel was patrolled by French ships that threatened to ruin the English wool trade, and for two years the southern coast of England had been plagued by French pirates, who had reduced the town of Southampton to little more than a smoldering shell.

Edward had been planning a large military invasion for some months. Inevitably, word of the preparations had reached Philip, and a huge French fleet, detailed to blockade the ports and prevent the English army from landing, had been gathered from the coasts of Normandy and Picardy. Now, looking toward the coast, Edward saw that the French were ordered in a tight position, their vessels anchored and chained together in three lines across the mouth of the river Zwin.

After a night spent anchored within sight of the intimidating masts and armored prows of the French fleet, Edward had directed his ships to approach the mouth of the Zwin at around 3:00 p. m. They came up from the southwest, with the sun and the wind behind them. As he moved into view, he must have felt a pang of anxiety, even fear. He was about to fight one of the largest naval forces ever assembled in the Channel. Failure would mean utter ruin.

In the first line stood some of the largest ships ever launched into the Channel, cogs carrying hundreds of men with crossbows bristling, including the Christopher, a giant ship stolen from the English some months earlier. Behind them bobbed the smaller ships; in the third line were merchant boats and the royal galleys.

The English attacking force at Sluys had sailed to France against the pleas and warnings of Edward III’s ministers, led by Archbishop Stratford of Canterbury, who had warned him that the size of the French fleet meant certain death and destruction to the smaller English armada. Edward, stubborn and determined, had set out from the mouth of the river Orwell in East Anglia, leaving his advisers stung by a harsh rebuke: “[T]hose who are afraid can stay at home.”

A medieval sea battle was much like a land battle. There was little maneuver or pursuit. When two navies came together, it was a collision, followed by boarding and a desperate, bloody fight at close quarters. Although some large weapons like catapults and giant crossbows were carried on board, by and large it was bolts and arrows and the violent smash of men-at-arms’ maces and clubs that did the damage. “This great naval battle was so fearful,” wrote the chronicler Geoffrey Baker, “that he would have been a fool who dared to watch it even from a distance.”

The French, commanded by Hugues Quiéret and Nicolas Béhuchet, were undone by their decision to shackle their ships together in three ranks across the mouth of the Zwin, thereby sacrificing all mobility for what seemed like the security of close ranks. The two rows of vessels behind the front line were barred from fighting by the ships in front of them, and as the English attacked, the French found it impossible to evade a head-on assault.

The air filled with the blast of trumpets, the throb of drums, the fizz of arrows, and the splintering sound of huge ships smashing into one another. The English fleet attacked the French in waves. Each ship rammed into an enemy vessel, attaching itself with hooks and grappling irons as English archers and French crossbowmen traded hailstorms of vicious arrows and bolts. The bowmen took up high vantage points, either on the raised end-castles of the boat or on the masts, and when they had killed enough of the defenders, men-at-arms clambered aboard the enemy ship to mete out death and destruction at close quarters.

The French were trapped and slaughtered. “It was indeed a bloody and murderous battle,” wrote Jean Froissart, the French poet and chronicler, whose account of the Hundred Years War was one of the great works of contemporary history in the fourteenth century. Froissart noted that “sea fights are always fiercer than fights on land because retreat and flight are impossible. Each man is obliged to hazard his life and hope for success, relying on his own personal bravery and skill.” Between sixteen thousand and eighteen thousand French and Genoese were killed, either cut down on deck or drowned. Both French commanders died: Quiéret was killed as his ship was boarded, and Béhuchet was hanged from the mast of his ship.

The battle of Sluys was one of the greatest early naval victories in English history. The English and their Flemish allies cheered and celebrated the victory in disbelief. Almost the entire French fleet had been captured or destroyed, eliminating at a stroke much of the danger to English merchant ships in the Channel and Philip’s ability to blockade the Continental coastline. The death toll alone on the French side was shocking. The English monastic chronicler Thomas of Burton wrote that “for three days after the battle in all the water of the Zwin . . . there seemed to be more blood than water. And there were so many dead and drowned French and Normans there that it was said, ridiculing them, that if God had given the fish the power of speech after they had devoured so many of the dead, they would thereafter have spoken fluent French.”

Centuries later the Elizabethans and Jacobeans thought of Sluys as a historical precursor to the Spanish Armada. The sixteenth-century writer of the play Edward III (likely co-written by Shakespeare, although the following passage is not thought to be his) imagined the aftermath:

Purple the sea, whose channel filled as fastWith streaming gore, that from the maimed fell,As did her gushing moisture break intoThe crannied cleftures of the through shot planks.Here flew a head, dissevered from the trunk,There mangled arms and legs were tossed aloft,As when a whirlwind takes the summer dustAnd scatters it in middle of the air.

Thus the battle of Sluys was later immortalized in English maritime history.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from The Plantagenets by Dan Jones. Copyright © 2013 by Dan Jones.