The wildly popular videogames Doom and Quake have been accused of everything from preaching Satanism to inspiring the Columbine school shooting. By comparison, the latest game from one of the original Doom and Quake designers could be found guilty of nothing worse than inspiring children to set up lemonade stands.

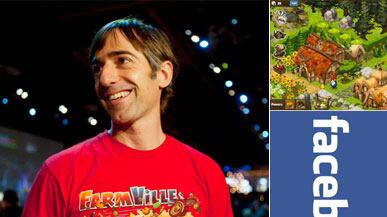

If John Romero's earlier games were marked by gore, his Ravenwood Fair is as clean as a Singapore sidewalk. In Quake, gremlins feasted on corpses. In Ravenwood Fair you guide a raccoon or bear around a forest, felling trees and erecting carnival attractions in the clearings. Should you encounter a monster, you simply scare it off with a few mouse clicks. But though Ravenwood Fair lacks the bluster of Romero's early shooters, it is on pace to become his most popular game to date. In the two months since its launch, it has attracted more than 4 million monthly players — in large part because you play it on Facebook. Facebook and its 500 million users make up the largest potential gaming platform ever—a fact that has not been lost on entrepreneurs. The founder of Farmville company Zynga, Mark Pincus, is on pace to be Silicon Valley's next billionaire, and even traditional gaming companies are getting in on the action, with Electronic Arts buying Playfish for $400 million last year.

Despite their profitability, Facebook games have always lacked respectability from traditional gamers—"Skinner boxes" is the common put down. Now that may change, as industry pioneers like Romero, who co-founded a Facebook gaming company called Loot Drop, are increasingly winning their bread on the social network. In fact, the lead designers of three different Civilization titles, among the most-beloved PC games of all time, are now working on Facebook games, including Sid Meier himself, who kicked off the series in 1991.

Beyond potentially reaching millions of users, many videogame pioneers enjoy the particular back-to-basics design challenge that Facebook presents. During the 1980s, when the videogame industry was still in its infancy, designers worked individually, or in small teams, with tight deadlines and tiny budgets.

But the rise of 3D graphics changed that equation. As the graphics grew more complex, gaming companies began investing hundreds of millions of dollars in their development, with design teams swelling to hundreds of people. On such large teams, it became impossible for any individual designer to own more than a handful of features in a game. "I was starting to feel like there were whole months going by when I wasn't doing actual game design," laments Brian Reynolds, chief game designer at Zynga. (During an earlier era, he coded Civilization II almost single-handedly in a London apartment.)

If John Romero’s earlier games were marked by gore, his Ravenwood Fair is as clean as a Singapore sidewalk.

Videogame design suddenly resembled a Hollywood production. Romero, for one, recalls working with 75 people for four years on a game, before it was finally canceled. Or as Soren Johnson, who led the Civilization IV design team and now works on a Facebook game for Electronic Arts, puts it: Involvement in a big console game "was almost like a degree program."

Facebook games, on the other hand, are more like sped-up seminars. Because they're played in a Web browser, with millions of alternative distractions just a mouse click away, users won't wait too long for them to load, taking complex 3D graphics—and the large design teams needed to support them—off the table. And Facebook gaming companies like to get the games out speedily so that they can analyze user behavior and refine the designs. As a result, Facebook games rarely take more than a few months to develop, with the projects hardly ever employing more than a few dozen people. Johnson, for example, is working with about 20 people on a Facebook version of Dragon Age—a small fraction of the people plugging away at Dragon Age 2 for the consoles. The games themselves are quite different than what the designers are used to, as the average Facebook gamer— a 43-year-old woman—doesn't have much in common with your typical hardcore gamer kid. "A lot of unlearning needs to be done with the Facebook stuff," says Romero. For example: When typically designing a AAA game, you offer in-game items as rewards for accomplishing difficult tasks; on Facebook, however, almost everything is available for purchase the moment you load the game. "They want to buy things in the store immediately," Romero says. "Even though the game lets them get stuff over time, people want a short cut."

Some players go overboard, blowing through hundreds or thousands of dollars. Such players are, in fact, the core of a Facebook's gaming-company business. "There are certain industries in which the majority of revenues come from the minority of the customers," game designer Ian Bogost told Gamespot last month. "When you have a game that does not have a spending cap and the vast majority of revenue is coming from a minority of players, 10 percent of players generating 90 percent of revenues, how do we feel about that?"

Most Facebook game designers contend that Facebook is in fact preferable to the retail market, where players must fork over $60 for a game they've never tested. "To me it feels like a much more fair business model to the player in that they're only paying for things they see value in versus going to a store and looking at a box and really hoping that it's good," says Romero.

Still, despite the creative freedom of the Facebook platform, a player forking over $60 for a premium title would seem to have a larger variety of choices than a player logging onto Facebook. Nearly all of the most popular games on Facebook follow the same formula: Players create a digital property—a farm, a fair, a castle—and show it off to their friends. The similarity of the games explains, in part, the reluctance of other traditional gamers to sign up for Facebook, even as Facebook brings games to new swaths of the population.

The uniformity of Facebook games is probably a sign of the genre's infancy. It is in part for this reason that gamers eagerly anticipate what Meier will do with Civilization for Facebook. On Facebook, Meier says, "We can emphasize other parts of the game that we don't emphasize with the single-player game." In some ways, it's the perfect platform for the subject: "Civilizations, by definition, are groups of people working together." Fans of the Civilization games have typically favored competition and combat, but the Facebook game, Meier says, will emphasize "needing to work together with other people, creating strategies together, and having an important role on the team." (Combat will still play a role: "All the things that you love about Civilization, you'll find in Civilization for Facebook," Meier says.)

Romero, for his part, plans to work within the established Facebook formulas. He doesn't plan to bring the violence of Doom and Quake to Facebook. "I've done every kind of game pretty much," Romero says. "The shooter stuff was just in the '90s."

Ben Crair is the Deputy News Editor of The Daily Beast.