Just before 8 p.m. on Oct. 8, 2020, a 911 dispatcher in Sanders County, Montana, received a strange phone call. The woman on the other end said she was calling from a gas station in Hot Springs—a tiny, rural town located on the Flathead Indian Reservation. Her voice was shaky, her delivery broken. She could not give her exact address. But one thing came through loud and clear: “I need the police,” she said. “...I killed someone.”

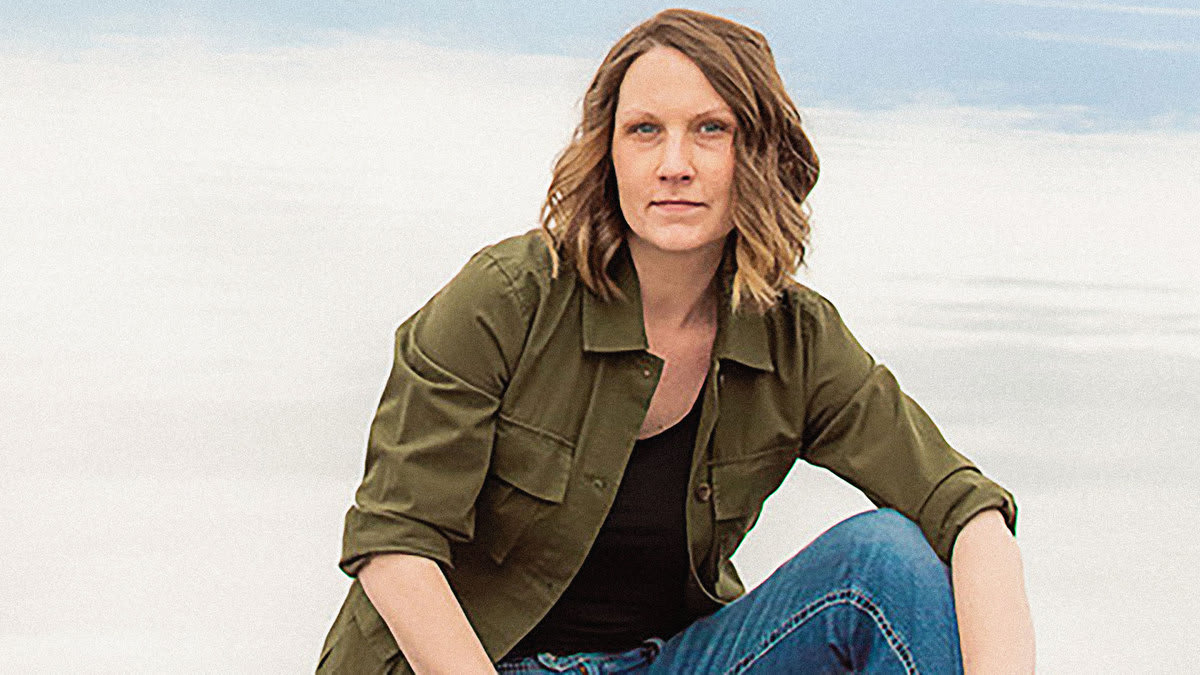

The woman on the phone that night was Rachel Bellesen, the 38-year-old coordinator at the nearby Abbie Shelter for domestic violence survivors. The shelter director, Hilary Shaw, described Bellesen as a "powerhouse" and a natural caretaker, one of her most talented shelter employees but also one of the quietest. Bellesen once sewed her mother-in-law a quilt out of her grandchildren’s old t-shirts, Shaw said. When a friend was having trouble conceiving, she volunteered to carry her twins.

Bellesen was also a survivor of domestic violence herself—the victim of a years-long cycle of physical abuse that propelled her toward the night in question, standing at a swimming hole outside Hot Springs, alone with her ex-husband and a Glock26 in her hands.

And Shaw is one of several advocates now pressuring prosecutors to turn from tradition and clear Bellesen of her crime—completely.

“An injustice has been done,” Shaw told The Daily Beast in an interview last week. “A mistake has been made. And the right thing to do is to fully vindicate Rachel."

Bellesen did not have an easy upbringing. Growing up in Washington State, she lived with an alcoholic mother and a rotating cast of father figures—one of whom Bellesen says sexually abused her until she was 15. When she became pregnant by another man at age 16, her mother moved to Montana and refused to take her pregnant daughter with her. She says her mother told her: “We’re not taking pregnant kids to Montana.”

The man who impregnated Bellesen was Jacob Glace, a local drug dealer who lived down the street from her in Leavenworth, Washington. The day they met—when Glace came to her friend’s house to sell them weed—he was 23, and she was 15. The pair began dating quickly thereafter, and she was pregnant with her first child in less than a year. When her mom left for Montana, the now-homeless 16-year-old moved in with Glace. She had her second child one year later.

Bellesen says Glace was routinely abusive. In 2004, court records show, a neighbor called 911 to report that Glace had dragged Bellesen out of her apartment by her hair and thrown her to the ground. When police arrived, according to an incident report, they found Glace “extremely intoxicated” and the door to the apartment splintered. Bellesen told officers she was trying to separate from Glace but that he wouldn’t leave her alone. The officers documented redness on the left side of her face and scratches up her arm; she presented them with a tuft of hair she said he’d pulled out. Glace pleaded guilty to fourth-degree assault and the couple divorced later that year.

Without Glace, who she says always controlled the couple’s finances and social life, Bellesen struggled to take care of two young children on her own. She grappled with alcoholism—a common response to domestic violence—and was briefly homeless. As a result, she lost custody of her two children. With nowhere else to turn, she says, she reached out to her mom, who offered to help her relocate to Montana. At age 21, she got on the train with nothing more than a backpack of belongings and settled in the small mountain town of Whitefish.

But Glace would not leave her alone. Although he had full custody, he let Bellesen take the children and came to Whitefish often to visit them. In 2009, he moved to Montana full time, to a tiny town an hour and a half south of where she lived. Bellesen said he continued to harass her from there, constantly threatening to take away the kids if she didn’t do what he wanted. She continued to struggle with alcoholism, and says she “basically lived day to day,” working entry level jobs and entering into even more unhealthy relationships with men.

By 2012, Bellesen says she was determined to turn her life around. She was working on staying sober and had enrolled in a college program to become a substance abuse counselor. That was also the year she met Corey Bellesen, her husband of nearly a decade, on Match.com. (They were married in December of that year, she said, “which many might think was rather fast, but he is my best friend and I can't imagine life without him.”) She started volunteering at the Abbie Shelter and quickly found herself drawn to working with other domestic violence survivors. The shelter hired her on full-time in 2018—the same year she completed her bachelor’s degree.

Though Bellesen was sober, stable, and in a job and relationship she loved, she says Glace continued to exert control over her life—mostly through their children. On the night of Oct. 8, according to her attorney, Bellesen agreed to meet with Glace outside of his home because of a threatening comment he had made about their son. She was hoping to smooth things over without anyone getting hurt, but when she arrived, she says, Glace attacked her and attempted to rape her, ripping her clothes and leaving scratches and bruises across her body.

In the heat of the moment, she says, it felt like the last 16 years had never happened; like she was a teengaer again, and he was finally going to kill her. She pulled out her handgun and shot him.

There are no national statistics on how often women successfully cite self-defense in the murder of their abusive partners, but the numbers surrounding it paint a grim picture. Nearly 60 percent of people in women’s prisons have a history of physical or sexual abuse, according to the ACLU; as many as 90 percent of those incarcerated for killing a man say they were previously been abused by him. Feminist legal scholars argue that self-defense law is biased toward men, favoring cases of one-off attacks by strangers when most violence against women is perpetrated by someone they know.

In 2006, Cyntoia Brown, a 16-year-old from Nashville, Tennessee, was convicted of first-degree murder—for killing an older man who’d picked her up for sex when she thought she saw him reaching for a gun. At the time, Brown was in an abusive relationship with a drug dealer who forced her into prositution; she spent 15 years in jail before being granted clemency in 2019. That same year, in upstate New York, Nicole Addimando was convicted of second-degree murder for killing the husband she said sexually and physically abused her for years. Brittany Smith, a young woman in Alabama, tried to use the Stand Your Ground law as a defense after killing her alleged rapist in 2018. Sexual assault examiners found 33 injuries on her body—consistent with being held down, strangled, and raped—but a judge ruled against her, saying she doubted Smith had reason to believe she was in serious danger when she pulled the trigger.

On Oct. 8, 2020, after Bellesen made her 911 call, police arrived and took her to a nearby hospital. She told two nurses that her ex-husband had attempted to assault her; officers there collected her clothes and took pictures of the injuries to her body. When they asked to question her further, she invoked her right to have a lawyer present. But her husband told officers she had given him the exact same story when he arrived to help her that day: There was a struggle, Glace tried to rape her, and she shot him in self-defense.

The next day, the county attorney charged Bellesen with deliberate homicide.

One thing we do know about domestic violence is that abusers are often repeat offenders. One study of nearly 700 British men arrested for domestic violence found that half of them were involved in at least one more incident in the next three years. Nearly one in five re-offended with a different partner than the one they initially abused.

In the years after Bellesen and Glace divorced, Glace was charged three more times with domestic violence. In 2010, shortly after moving to Montana, he was found guilty of partner or family member assault after he pushed his new wife to the ground and choked her. In May 2020, he was charged with the same crime in another county after he allegedly screamed at a different partner and attempted to rip the phone out of her hands when she called 911. The month before, he had been charged with assault in yet another county, after allegedly hitting his girlfriend in the face, smashing a chair, and slamming her into a wall when he barged into the bedroom, yelling.

“He was very abusive across the board, sexually, physically, emotionally and financially,” the third woman told the Daily Inter Lake newspaper at a court hearing, adding that the two had lived together until Glace hit her in front of her kids.

Bellesen was in jail for three weeks before prosecutors lowered bail enough for her to get out. For the next several months, Bellesen says, she was too traumatized to leave the house. She had panic attacks just thinking about going to the grocery store; loud noises and close contact with others terrified her. The county, meanwhile, had called in a state assistant attorney general and a private attorney from Missoula to aid in the prosecution. (The private attorney, former county prosecutor Thorin Geist, previously won a “dishonorable mention” from the ACLU of Montana for refusing to let a pregnant woman change her hearing schedule to attend drug treatment. A week later, he charged her with criminal endangerment of a fetus for testing positive for narcotics.)

Bellesen eventually secured the help of a pro-bono defense attorney, Lance Jasper, who told The Daily Beast he was convinced of her innocence after one conversation. He was so convinced that the state had no case, in fact, that he made them an offer he’d never attempted in more than 20 years in practice: He told the state he would show them his full case file—the entirety of Bellensen’s defense—and would give them a full year to prosecute if they still wanted to do so. After that, the case would be dismissed with prejudice—meaning they would not be able to take it up again, and Bellesen’s record would be cleared.

The prosecutors refused. Instead, on April 9, three months before the case was supposed to go to trial, the state filed a motion to drop the case without prejudice. They claimed they were still waiting on the results of forensic tests and needed more time to decide whether or not to proceed. Bellesen’s name would not be cleared; she would instead have to wait until an unspecified “later date” to know if she would have to stand trial.

Prosecutors do not usually drop such cases with prejudice. Karla Fischer, an attorney and consultant who has worked on more than 200 self-defense cases in which domestic violence was involved, said she can remember two in which the charges were dropped at all—never mind with prejudice. Prosecutors are often under pressure from the deceased’s family to seek justice, or from the community to seem tough on crime, she said. Often, they will offer battered women a plea deal to a lower charge, but rarely will they drop the charges completely.

“I think he’s done the right thing,” Fischer said of the prosecutor in this case. “After he gets more information, and if he still doesn't have the evidence to prosecute, then he should do the right thing and dismiss them with prejudice.”

But Bellesen’s advocates are not satisfied. Shaw, the director of the Abbie Shelter, argued that the charges should never have been filed in the first place, and would hang over Bellesen for her entire life if they were not dismissed entirely. Dismissing them without prejudice, she said, “is not acknowledging the harm that has been done” by the prosecution. “It really just seems like we’re being told we should be happy with what we’ve got, and we aren’t,” she said.

Jasper, meanwhile, said he felt the charges were riddled with sexism. If a man had shot another man in rural Montana after an attempted rape, he said, prosecutors would never have charged him with murder. “If this was flipped around any other way, they would have thrown her a parade,” he told The Daily Beast.

Even Fischer said she was happy Bellesen had advocates pushing for her full vindication.

“Victims—especially those who have lived in a chronic violence situation for a long time—they’ve never had a chance for it to be over,” she said. “Something that is final, that means this is really over, would mean so much to her psychologically.”

“The definition of advocacy is to push for something that’s really premature,” she added. “We want to push for something better and I think they’re right to push for this to truly be over for this woman.”

Jasper says he plans to oppose the state’s motion at the next hearing on May 25. Bellesen, meanwhile, is working from home, helping out the Abbie Shelter as best she can from behind the scenes and completing an internship with a food magazine. (She has always been an avid baker.) She says the behavior of prosecutors in her case, along with her work at the shelter, has opened her eyes to the injustices of the legal system and emboldened her to speak out. Despite her shyness, she is talking occasionally to the media, and has even allowed a camera crew to follow her around for a possible TV episode.

“Instead of continuing to hide and feel shame for the abuse that I have suffered, I am empowered to stand up and speak out against what has happened to me.” she told The Daily Beast. “The problem is so much bigger than just my case.”

Shaw, who has launched a public pressure campaign to get the state attorney general to drop the charges with prejudice, said it is just this transformation that makes Bellesen’s case so tragic.

“She's the success story,” Shaw said. “She survived an extremely challenging childhood with great risks, survived this horrible, abusive relationship, met her husband, had this thriving marriage, and created this really wonderful, thriving life.”

“She made it to the other side and Jake could not leave her alone,” she added. “That's why this case is so painful, is he is still abusing her from the other side of the veil.”