With Democrats invoking the so-called “nuclear option” on Thursday, Washington was aglow with partisan vitriol as by a simple majority vote, Democrats forced the most significant change to Senate rules in decades.

As a result of the vote—attached as a procedural motion to the nomination of Patricia Millett to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals—debate on presidential nominations to any office, save the Supreme Court, can be ended by a simple majority vote.

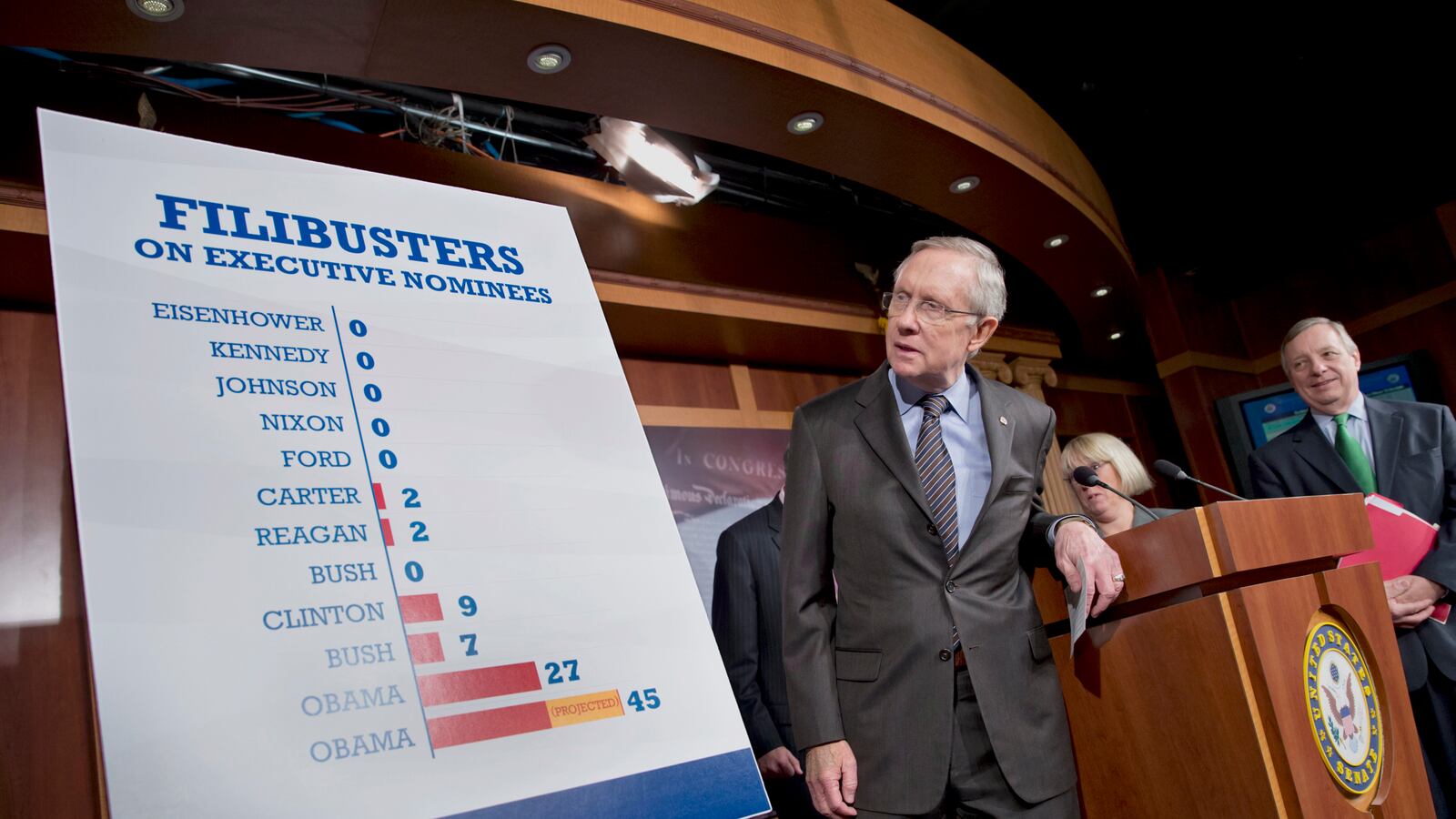

The landmark change came amid increasing frustration among Senate Democrats that Republicans were blocking an inappropriate number of presidential nominees by not supporting motions to end debate or cloture, which had previously required a 60-vote threshold. (Ending debate on legislation will still require 60 votes; the rule change only applies to nominations.)

Reid’s maneuver was called the “nuclear option” because it flouted precedent. Traditionally, under Senate Rule 22, a two-thirds majority is required to end debate on any decision to change Senate rules. However, during frustration over Democratic filibusters in 2005 during the Bush administration, when there was a Republican majority in the Senate, then-Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist (R-TN) established the idea of having the presiding officer of the Senate rule that only a simple majority was needed to end debate. This sparked outrage among Democrats, who first gave it the nuclear label. A major political standoff was only adverted when a bipartisan group of senators known as the Gang of 14 negotiated a compromise.

Since then, using the nuclear option to fix the filibuster has repeatedly been pitched as a possibility, particularly by a group of recently elected progressive Democrats, most notably Jeff Merkley (D-OR), but had been opposed within the Democratic caucus by many veteran senators like Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and Pat Leahy (D-VT).

However, as Feinstein said outside the Senate chamber Thursday, the level of obstruction posed by the GOP recently was unprecedented. “It’s never, ever, ever been like this” Feinstein told The Daily Beast. “You reach a point where your frustrations just overwhelm and things have to change.”

Other senators thought Reid had made a rash decision and thrown away an opportunity to compromise. Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) said that a group of senators were working to come up with yet another compromise and bemoaned the fact that they were not given “the time to try to come up with something that might have produced a different ending.” Collins said that her group, which was “a subcommittee” of the bipartisan group of senators that worked on the shutdown, had “met Monday night for dinner and talked about this issue.” In the opinion of the moderate Maine Republican, Reid “made a terrible mistake, contrary to not only the longstanding rules of the Senate but our tradition of respecting minority rights.”

Proponents of filibuster reform like Merkley disagreed. In their opinion, the change in Senate rules had already happened in 2005. Merkley said that the power of minority to obstruct judicial nominations had really been ended in that standoff. The Oregon Democrat thought the precedent had already been set and had no illusion that if Democrats had not changed the rules, Republicans would the next time that they had the opportunity.

Of course, the big question facing many senators was what would happen if Republicans took control of the Senate after 2014 elections—if not sometime further in the future. Apparently, one McConnell aide jibed, “I’m looking forward to President Rubio stacking the courts.”

Democratic supporters of the move were more sanguine. Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), who had supported filibuster reform since he was first elected in 2010, felt confident that if Democrats were in the minority, “We can block an antithetical or abhorrent nominee based on the merits of the nominee without needing to resort to obstruction.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) warned that the presidential nominees for judgeships would be more ideological and more partisan in the future and that process would be more like nominees for the State Department. In Graham’s opinion, the filibuster was a powerful check to prevent the government from passing bad legislation. “Just think of the nutty ideas we had that they stopped and nutty ideas that they had that we stopped” said Graham. Now, the South Carolina senator thought there were no more checks to keep the level of partisan influence on the Senate from “going through the roof.”

Graham’s warnings of increased partisanship though paled compared to those of John McCain who warned apocalyptically, “When you change the rules with a simple majority, there are no rules and that’s the way it’s going to be.”