When Pedro Nava arrived in Rio de Janeiro in August 1918, he was 15 years old. He had come to live with his “uncle” Antonio Ennes de Souza in the smart neighborhood of Tijuca, in the north of the city. Ennes de Souza was actually a first cousin of Nava’s father, José, but José had died in 1911, leaving his family in straitened circumstances and forcing them to leave the city. When the time came for Nava to study seriously, his mother sent him back to Rio, into the care of Uncle Ennes de Souza.

He was immediately entranced by his elegant and vivacious Rio relations, and by one visitor to the house in particular—a niece of “Aunt” Eugenia named Nair Cardoso Sales Rodrigues. Describing the radiant Nair in his memoirs more than half a century later, he compared her to the Venus de Milo—with her “lustrous complexion, her red petal-like lips, her wonderful hair”—and recalled with perfect clarity the night they both heard about the epidemic known as espanhola.

It was late September, and as usual in the Ennes de Souza household, the papers were read aloud at the dinner table. They contained a report of 156 deaths on board the ship La Plata, which had sailed from Rio, heading for Europe, with a Brazilian medical mission aboard. The sickness had erupted two days out of Dakar on the west coast of Africa. But Africa was far away, and the boat was heading farther still. What concern was it of theirs? Not reported that night—perhaps due to censorship, or perhaps because the press did not consider it sufficiently interesting—was the progress of a British mail ship, the Demerara, that had stopped in Dakar on its way out to Brazil. It had arrived in the northern Brazilian city of Recife on September 16, with cases of flu on board, and was now heading south towards Rio.

After dinner, Nava went to sit by an open window with his aunt, whose back he obligingly scratched. Nair sat with them, and as she contemplated the tropical night, he contemplated her. When the clock struck midnight, they closed the window and left the room, but Nair paused to ask if they should be worried about the “Spanish’”sickness. Years later, Nava recalled the scene: “We were standing, the three of us, in a corridor lined with Venetian mirrors in which our multiple reflections lost themselves in the infinity of two immense tunnels.” Eugenia told her there was nothing to worry about, and they parted for the night.

The Demerara entered Rio’s port in the first week of October, without encountering any resistance. It may not have been the first infected ship to reach the capital, but from at least the time of its arrival, the flu began to spread through the poorer bairros or neighborhoods of the city. On October 12, a Saturday, a ball was held at the Club dos Diàrios, a favorite haunt of Rio’s coffee barons and other powerbrokers. By the following week, many of the well-heeled guests had taken to their beds. So had the majority of Nava’s fellow students. When he turned up at college on Monday morning, only 11 of the 46 students in his year were present. By the end of the day, the college had closed indefinitely. Nava, who was told to go straight home and not to dawdle in the streets, arrived at his uncle’s house, 16 Rua Major Ávila, to find that three members of the household had fallen ill since morning.

The city was totally unprepared for the tidal wave of sickness that now overtook it. Doctors kept up punishing schedules and returned home only to find more patients waiting for them. “Agenor Porto told me that in order to have some rest, he had to lie hidden inside his landaulet [car] covered with canvas sacks.” Food, especially milk and eggs, ran short. Cariocas—as inhabitants of Rio are called—panicked, and the newspapers reported the deteriorating situation in the city. “There was talk of attacks on bakeries, warehouses and bars by thieving mobs of ravenous, coughing convalescents . . . of chicken-stuffed jackfruits put aside for the privileged—the upper classes and those in government—being transported under guard before the eyes of a drooling population.”

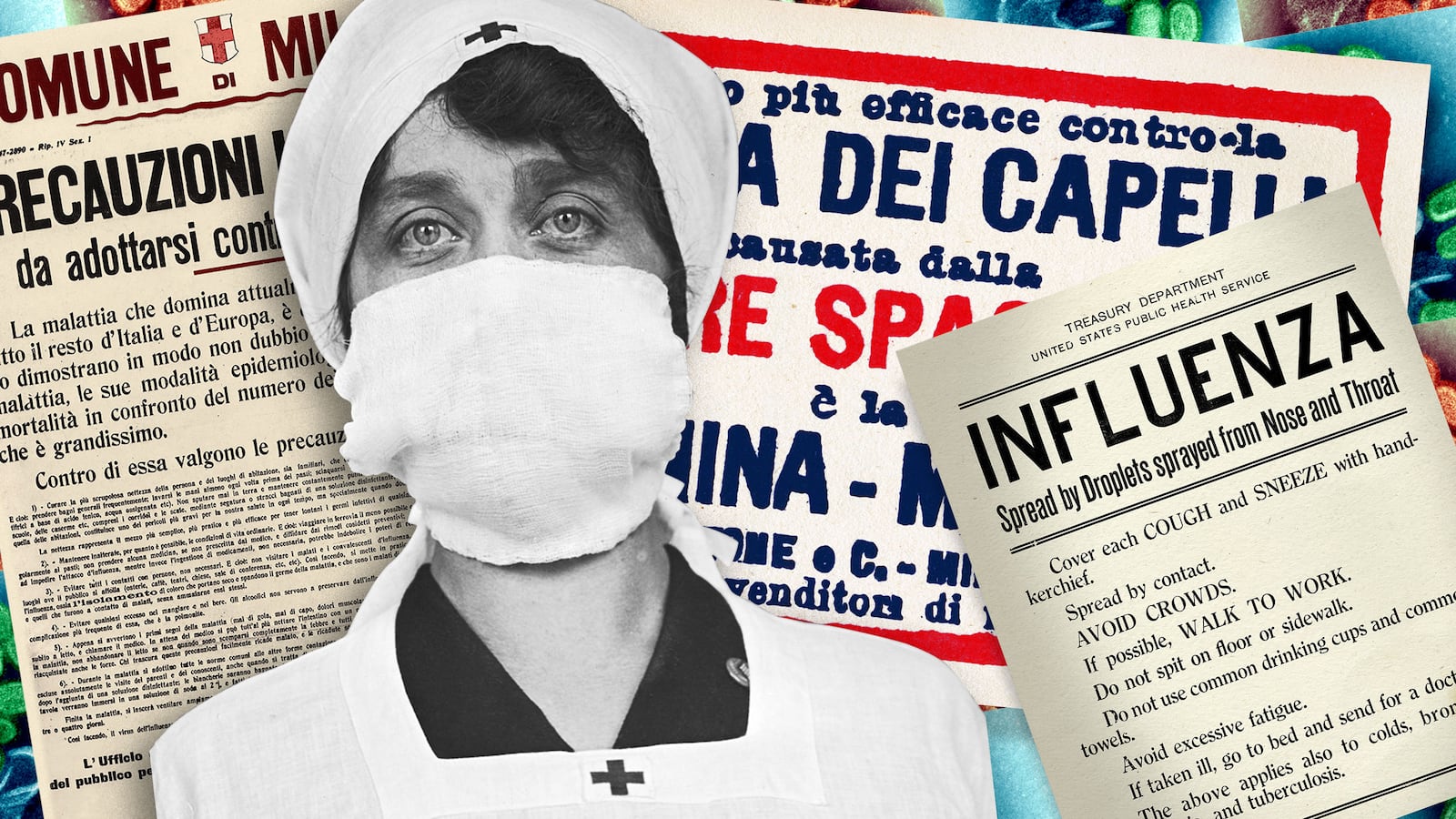

Warehouses were converted to keep people infected with the Spanish Flu of 1918 quarantined.

Universal History Archive/UIG via GettyHunger invaded the house on Major Ávila. “I got to know that drab companion,” Nava wrote. “After one day on thickened fish stock, another on beer, wine, spirits, and the dregs of olive oil, I can still remember the dawn of the third day. No breakfast, nothing to eat or drink.” Ennes de Souza, aged 71, donned a wide-brimmed hat, took up a defensive stick and a wicker basket, and accompanied by his convalescent nephew Ernesto, “pale with an unkempt beard,” went out to see what he could procure for his famished family. “After many hours they came back. Ernesto was carrying a bag full of Marie biscuits, some bacon and a tin of caviar, his uncle ten tins of condensed milk.” These precious stocks were strictly rationed by Aunt Eugenia, “as if the house on Major Ávila were Géricault’s raft after the shipwreck of the Medusa.”

One day, while out in the city, Nava recalled looking up at the sky and seeing a pumice-grey dome in which the sun appeared as a dirty yellow blot. “The sunlight was like sand in the eyes. It hurt. The air we breathed was dry.” His intestines rumbled, his head ached. Falling asleep on the tram home, he had a nightmare that the staircase on which he was standing was falling away beneath him. He woke up shivering with a burning forehead. Once home, he gave himself up to the sickness. “I kept on rolling down those stairs . . . The days of hallucination, sweat and shit had begun.”

At the time that Nava fell sick, Rio was the capital of a young republic, a military coup having brought the reign of Emperor Dom Pedro II to an end in 1889. Thirteen years later, when President Francisco de Paula Rodrigues Alves came to power, he set out to rid the city of infectious diseases, and in this he was aided by a doctor, Oswaldo Cruz. In 1904, as head of the General Board of Public Health, Cruz ordered a campaign of compulsory vaccination against smallpox. At the time, the vast majority of Brazilians had no grasp of germ theory. For many it was their first experience of state intervention in public health, hence something extraordinary, and poor cariocas rioted. The “Vaccine Revolt,” as it was called, was about more than one perceived violation, however. It was an expression of a broader class struggle over whom the city should serve—the Brazilian masses, or the European elite.

A decade later, vaccination had been accepted by most Brazilians, but Cruz’s unpopularity survived his death in 1917, and it was this legacy that shaped cariocas’ response to the new disease threat in 1918. On October 12, the day that the flu spread through the elegant guests at the Club dos Diàrios, the satirical magazine Careta (Grimace) expressed a fear that the authorities would exaggerate the danger posed by this mere limpa-velhos—killer of old people—to justify imposing a “scientific dictatorship” and violating people’s civil rights. The press portrayed the director of public health, Carlos Seidl, as a dithering bureaucrat, and politicians rubbished his talk of microbes travelling through the air, insisting instead that “dust from Dakar could come this far.” The epidemic was even nicknamed ‘Seidl’s evil.” By the end of October, when half a million cariocas—more than half the population—were sick, there were still those among Rio’s opinion makers who doubted the disease was flu.

By then, so many corpses lay unburied in the city that people began to fear they posed a sanitary risk. “On my street,” recalled one carioca, “you could see an ocean of corpses from the window. People would prop the feet of the dead up on the window ledges so that public assistance agencies would come to take them away. But the service was slow, and there came a time when the air grew filthy; the bodies began to swell and rot. Many began throwing corpses out on the streets.”

The bell at the gate of the São Francisco Xavier Cemetery in Cajú, in the north of the city, would not stop tolling, driving those who lived nearby almost mad. Gravediggers couldn’t dig fast enough; a thousand bodies awaited burial. To save time, they dug shallower graves. “Sometimes the ditch was so shallow that a foot would suddenly bloom on the earth,” recalled the writer Nelson Rodrigues. Amateur gravediggers were hired at advantageous prices. “Then came the prisoners,” wrote Nava: “Mayhem.” The convicts were enlisted to clear the backlog. Talk of horrors spread: of fingers and earlobes severed for jewels; of the lifting of the skirts of young girls; of necrophilia; of people buried alive. In the hospitals, it was said, at the same hour every night, “midnight tea” was served to those who were beyond help, to speed them on their way to the “holy house”—as coffin sellers euphemistically referred to the cemeteries.

Were the rumors true, or were they some kind of collective hallucination, one city’s imagination let loose by fear? In the end, Nava concluded, it didn’t matter, because the impact was the same. Terror transformed the city, which took on a post-apocalyptic aspect. Footballers played to empty stadiums. The magnificent Avenida Rio Branco was deserted, and all nightlife ceased. If you caught a glimpse of a human being in the streets, it was fleeting. They were always running, black silhouettes against a blood-red sky, their faces contorted in a Munch-like scream. “It just so happens that the memories of those who lived through those days are colorless,” wrote Nava, who may have experienced that strange distortion of color perception reported by other patients, too. “No trace of early morning tints, shades of blue in the sky, twilight hues or moonlight silver. Everything appears covered in an ashen grey or a rotten red and brings back memories of rain and funeral rites, slime and catarrh.”

When he rose from his sickbed, thin and weak, a servant told him that the girl he idolized, Nair, was now seriously ill. Struggling up the stairs, he peered around her door and was shocked by what he saw. Gone was the radiance, gone the lustrous complexion. Her lips were chapped and livid, her hair dull, her temples bony and concave. “She was so changed it was as if she had turned into another person, as if some kind of demon were haunting her.”

Nair died on November 1, All Saints’ Day, by which time the epidemic was receding and life in Rio was returning to normal. Nava’s enduring image of her was of “a marble bride” in a white dress, lying in a white coffin that the Venetian mirrors at 16 Rua Major Ávila reflected ad infinitum, her lips parted in a sad smile. “She belonged to the past now, as distant as the Punic Wars, as the ancient Egyptian dynasties, as King Minos or the first men, errant and miserable.” From over fifty years’ distance, the retired doctor bade her farewell: “Sweet girl, may you rest in peace.”

Excerpted from Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World by Laura Spinney. Copyright © 2017. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.