This summer the Red Hot Chili Peppers played tribute to their founding guitar player, the late Hillel Slovak, on the 29th anniversary of his death with a cover of Jimi Hendrix’s iconic “Fire.” It was a song that Slovak was known to make his own back when the California funk-rock quartet, one of the most long-lasting and popular bands of the past 30 years, were filling America’s club circuit with sweaty energy and shirtless bravado.

The Peppers have performed this tribute to Slovak on several occasions, but there was something special about that June night. For one of the first times since Slovak’s death in 1988, the band were joined by another founding member, their original drummer Jack Irons.

Judging by the look on bassist Flea’s face, it was a powerful and emotional moment for the band. And for their longtime fans, or anyone with an interest in the rise of American alt-rock, it was an unexpected but welcome sign that Irons, one of the world’s greatest drummers, was now actively taking control of his legacy.

It’s hard to argue that someone who was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame could ever be considered underrated. But in Irons’ case, it’s true. Once is just not enough. After all, he was instrumental in the creation of not one, but two, of America’s most influential and beloved rock bands: the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Pearl Jam.

As Flea noted while introducing Irons’ opening set at their Madison Square Garden show, the man otherwise known as Michael Balzary first met Irons in the sixth grade. They went on to form the Red Hot Chili Peppers with Slovak and their Fairfax High School classmate Anthony Kiedis. The group was famously conceived as a goof, with their friend Anthony rapping his poem “Out in L.A.” while the band improvised a groove. But the chemistry was undeniable, and they were an immediate live hit in the Los Angeles scene. But Flea, Irons, and Slovak were already committed to their primary group What Is This?, and when the Red Hot Chili Peppers unexpectedly gained a local following, both Slovak and Irons had signed a record deal, and weren’t available to play on the Chili Peppers’ 1984 self-titled debut.

After What Is This? began to fizzle out, both Slovak and Irons eventually rejoined the Chili Peppers. (Cliff Martinez, the drummer who played on the Chili Peppers debut and the 1985 follow-up Freaky Styley, would go one to be an innovative film composer with a focus on synth-soaked dread, scoring Sex, Lies, and Videotape, The Neon Demon, and Drive.)

1987’s The Uplift Mofo Party Plan is the only album to feature all four founding members of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and their only official album that Irons ever played on. It’s also the best album from their pre-breakthrough ’80s period. Before the Chili Peppers would mature into songwriters that contemplated mortality and the cost of Los Angeles’ seedy glamour, they were all about forward motion, spastic rhythms, and sex. And though they were led by an embryonic Kiedis who was still uncomfortable with melody, Irons’ hard swing made sure the Peppers’ music had punk’s visceral impact and funk’s buoyant bounce; even at their most frantic, Irons maintained a steady groove.

(Though it should be noted that the album’s pro-”real instruments,” anti-hip-hop jeremiad “Organic Anti-Beat Box Band” hasn’t aged well at all, but this was all when rockism was a thing people cared about. They’ve toured with enough rap acts since then to have surely gotten over any dated ideas about genre “authenticity.”)

The Uplift Mofo Party Plan was an underground hit thanks to songs like “Fight Like a Brave,” but during the tour to support it, both Kiedis’ and Slovak’s drug addictions increased. Shortly after Slovak was sent home from tour in 1988, he was found dead of a heroin overdose.

Irons was devastated by Slovak’s death and quit the Chili Peppers, saying that he didn’t want to be in a band where his friends were dying. He suffered a mental breakdown and became clinically depressed, eventually admitting himself into a psychiatric hospital, where he was diagnosed with bipolar manic depression.

Irons eventually returned to playing music, joining the band Eleven alongside his former What Is This? bandmate Alain Johannes and keyboardist Natasha Shneider. In 1990, he ran into his friend Michael Goldstone, an A&R man whom he knew from his What Is This? days, at a party in San Diego, and learned that his services were requested.

Mother Love Bone, the promising and heavily hyped group that Goldstone had signed, had just lost their charismatic lead singer Andrew Wood to a drug overdose, and were looking to rebuild. They’d already picked a new name and added a guitar player, and now they needed a new singer and a new drummer. Would Irons be interested in joining Mookie Blaylock?

Irons famously turned down the offer, but told Blaylock members Jeff Ament and Stone Gossard that he would pass along the demo to a local musician he knew, a surfing buddy named Eddie Vedder.

A name change as well as a massive sea change in American rock music would follow. And after Vedder and the rest of the group recorded their world-conquering debut Ten, Irons asked his old bandmates in the Chili Peppers if they would take this new band Pearl Jam on the road with them, ensuring them vital early exposure.

But not only did Irons start one world-conquering band and help create another—which is more than enough for any resumé—he later helped Pearl Jam find footing during a precarious moment in their career.

In 1994, the band fired drummer Dave Abbruzzese during the making of their third album Vitalogy, as Abbruzzese’s embrace of the spoils of the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle put him at odds with Vedder’s distrust of the trappings of fame.

By that time, Pearl Jam were unquestionably the biggest band in the world, but their swift rise had taken a toll. They were dazed by their sudden popularity and wounded by accusations of careerism and insincerity. Vedder was dealing with a stalker and guitarist Mike McCready was struggling with substance abuse, and the entire band was reeling from a protracted legal battle with Ticketmaster that had made their tours a logistical nightmare. Irons arrived right in time. In a 1997 Spin cover story on the group, the band members called him a grounding presence who helped center the fractured group.

“Jack’s personality, maturity, and generosity have really helped us communicate with each other,” says Gossard. ”It feels like this is how it was intended to be,” marveled Ament. “This should have been the band from the beginning,” stated Vedder. Irons gently downplayed his own role as peacemaker. “It’s just a new relationship,” he demurred. “It’s just one of life’s adjustments.” He knew then how easy it is to get sidetracked by extracurriculars. “The whole point is that we’re making music,” said Irons, echoing the now-familiar mantra. “We’re actually feeling something. And people can sense that.”

That article followed the group while touring behind 1996’s No Code, an album that found the band consciously trying to expand their sound and pare their audience down to something more manageable and less scarily mammoth. Irons pushed the band to embrace layered polyrhythms, jazzy meters, and Eastern-influenced song structures, most notably on “Off He Goes” and “Who You Are.” While many casual fans were befuddled by the turn away from their bombastic anthems, the album remains a favorite of many of the band’s still-diehard fan base, who love it for revealing how exploratory and contemplative the band could get.

When Pearl Jam decided to embrace straightforward anthems again with 1998’s Yield, Irons gave songs like “Given to Fly” his signature muscle, but his time in the group would come to an end a few months after the album was released.

He dropped off the tour, and later went public in an interview with Modern Drummer about his ongoing battles with manic depression. “We did fine musically and I think I played well,” Irons said of the the shows in which he performed, ”but the internal problems I’d experienced before, this inner life, still existed. It didn’t go away; it doesn’t go away with success. And when we came back from the tour, I was at my old point again, just mentally collapsed and exhausted.”

Irons pursued music in a more low-key fashion after leaving Pearl Jam, fearful that working on a larger scale would again take a toll on him. He rejoined Eleven for one more album, a few years before Schneider died from cancer. He did one-offs and sessions work with everyone from Hole to the Les Claypool to Perry Farrell, briefly joined the Wallflowers, and quietly released three solo albums that found him pairing soothing, new age-like synth meditations with his most complex and relentless drumming—proving that he hadn’t lost an inch of skill and was content to just make music for himself and whoever felt like listening. Even Vedder’s cameo on a cover of Pink Floyd’s “Shine On You Crazy Diamond” is just too abstracted to come across as a capitulation to the marketplace.

Irons never seemed to hold any grudges against the Red Hot Chili Peppers for continuing on without him, once telling Contact Music that “what happened to Hillel still haunts me today. I was devastated, torn apart and totally wrecked emotionally. I’m still suffering depression and still being treated for it. It was like my world was shattered too when he died and the dreams we dreamed died with him,” he said. “But I’m overjoyed by the band’s success today. What they’ve achieved is a massive tribute to Hillel. Had he lived, he would undoubtedly have become one of rock’s legendary guitarists.”

The drummer seemed content, for a while, to live a quiet life far apart from the bands he helped turn into household names, unconcerned whether their legions of fans were aware of his role in their beginning.

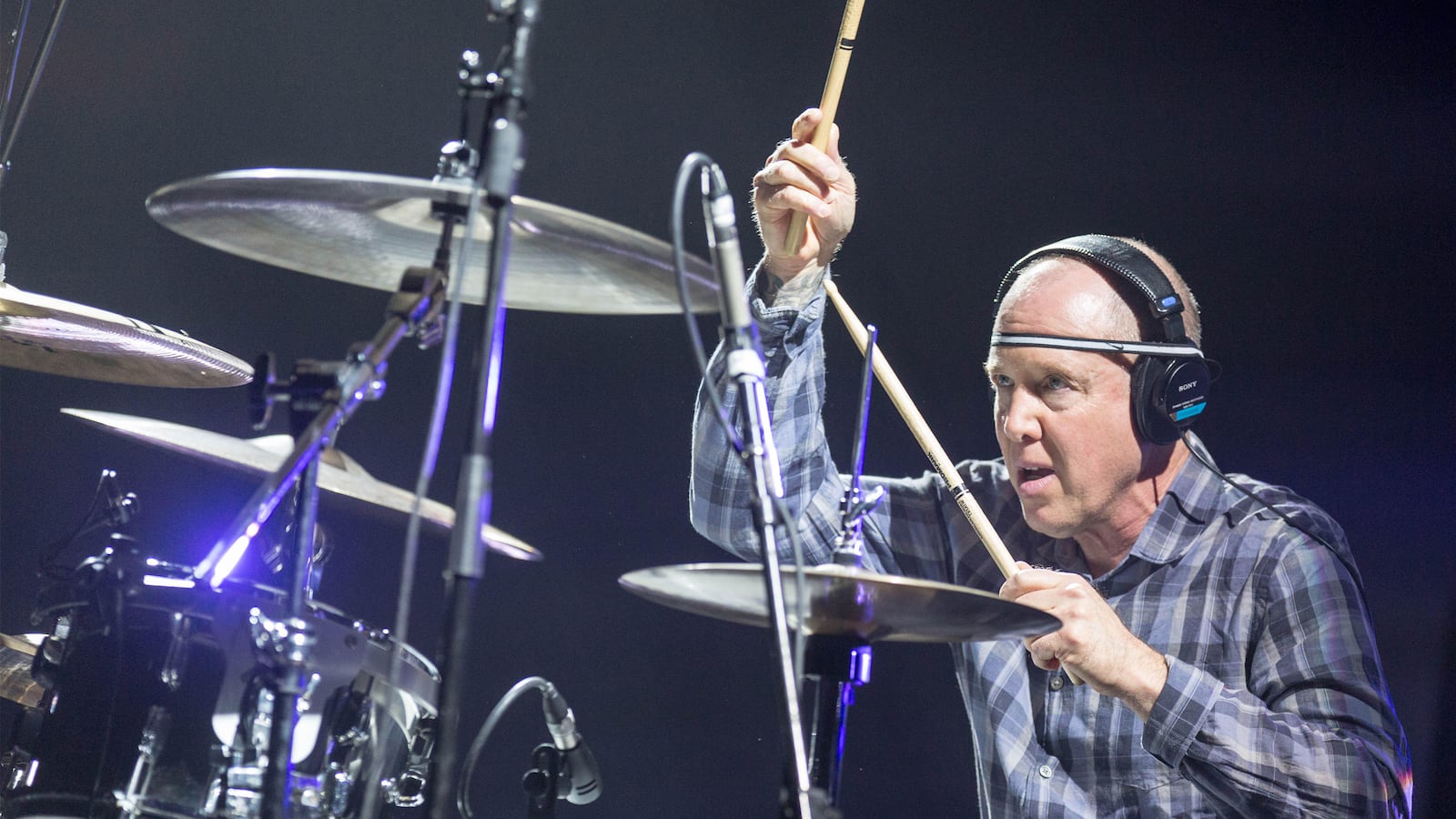

But in 2017, it seems, Irons has seemingly felt healthy enough to remind the music community of his impact. He opened for the Red Hot Chili Peppers this year, holding down his set with just his drum kit and synth-triggers, and the occasional vocal cameo by guitarist Josh Klinghoffer on “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.” It was an unusual sight under any circumstance, and certainly as the opening slot on an arena tour for mainstream hitmakers, but Irons had the resolve and fortitude to make the situation work.

Though Irons was oddly, and unfairly, not inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Pearl Jam (only the group’s first drummer, Dave Krusen, and their current drummer Matt Cameron were inducted; whereas Irons was inducted as a member of the Chili Peppers), he attended the ceremony as guests of Pearl Jam and joined in the set closing jam through of Neil Young’s “Rockin’ in the Free World.”

It’s unclear whether Irons’ recent activity can be attributed to old friends making a public showing of unity, or if he has plans to more actively play music publicly. (Through his manager, Irons declined an interview with The Daily Beast.) If he chose to play out more often, we’d all be the richer for it, and any band would benefit from his skills. But if he continues to live a mostly quiet life, he’s earned the right, and has already given us more than enough. And not just musically. He’s shown great bravery in talking openly about his struggles with depression for several decades.

Conversations about mental health are still woefully rare today, and were, sadly, practically unheard of in the 1990s—especially in the too-often macho rock music world.

If his honesty about his struggles with depression, and how therapy has helped him cope encouraged any of the devoted fans of his music to know it’s OK to ask for help, that’s a legacy that one of rock’s most underrated icons can be proud to claim.