The nearly two weeks of protest in Baltimore—which culminated last Friday when the city’s prosecutor, Marilyn Mosby, charged the six police officers involved in the death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray—brought a spotlight to the intense troubles faced by the residents of the West Baltimore neighborhoods where Gray lived. These neighborhoods, overwhelmingly African American, have incredibly high rates of unemployment and poverty. The median income is about the same as the poverty line for a family of four (around $24,000). Row after row of boarded-up vacant houses are visible almost the minute one pulls off the highway—they make up 13 percent of the housing stock.

Another grim statistic in which West Baltimore ranks high is in rates of incarceration and ex-offender status. More than half the prisoners who are released to the state of Maryland every year return to the neighborhoods of West Baltimore where they’re from. In late 2013, I spent more than three months in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood at the center of the recent riots and I came to know many of the men who’d come out of prison. As young men, they accumulated arrest records filled with minor drug charges and a few convictions like Gray’s, largely because the drug trade is the primary economy there. The men I knew struggled to get jobs and housing and to reconnect with their families after their release, all of which slowed their reintegration into society.

But there’s a bigger, more obvious barrier preventing them from feeling like full and active members of society again. They can’t vote.

Felony disenfranchisement has a long tradition. The idea that someone loses his right to vote when he is sent to prison for a serious crime (in the United States, a felony) is something we inherited from England. But in most of the democratic world, such laws were struck down or relaxed in the last few decades, viewed as a violation of internationally recognized human rights. Indeed, in many countries, including in South Africa and much of Europe, some or all prisoners can vote while they are still incarcerated. In a European Court of Human Rights decision striking down a blanket ban against prisoners voting in the United Kingdom, the court ruled that disenfranchisement was so severe a penalty it shouldn’t automatically be applied simply because someone was convicted of a crime: “Nor is there any place under the Convention system, where tolerance and broadmindedness are the acknowledged hallmarks of democratic society, for automatic disenfranchisement based purely on what might offend public opinion.”

The United States stands out because its felony disenfranchisement laws are among the strictest and because we have such a high incarceration rate. Nearly 6 million adults in the United States have currently or permanently lost their right to vote. And because African Americans are so much more likely to be convicted of a felony in this country, disenfranchisement falls disproportionately on them. Three in 10 black men can be expected to lose their right to vote at some point in their lifetimes.

The laws vary by state, but only two states, Vermont and Maine, allow prisoners to vote. Eleven still prevent people with felony convictions from voting even after serving their sentences. The rest restore the right to vote once offenders complete their full sentences, which in 31 states, including Maryland, includes parole and probation. Being on probation and parole means that these people are back in their communities, are expected to have jobs, pay child support, and obey the laws (plus the conditions of their release) under supervision of the criminal justice system—but they still can’t vote. “Some people can live in supervision for very long periods of time, for decades,” says Nicole D. Porter, of The Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy organization.

On April 9, before Gray’s death, the Maryland legislature passed a law that would restore the right to vote to people on parole or probation. It remains on Governor Larry Hogan’s desk, awaiting his signature or veto. It would expand the right to vote to an estimated 40,000 people. Similar legislation is being considered in Minnesota. But even if the laws change, it doesn’t mean people will be fully informed or understand that they can actually vote once they leave prison after a felony charge. “There’s a misunderstanding people have and what the laws are,” Porter says. “The collective consciousness is that if you have a felony conviction that you don’t have the right to vote.”

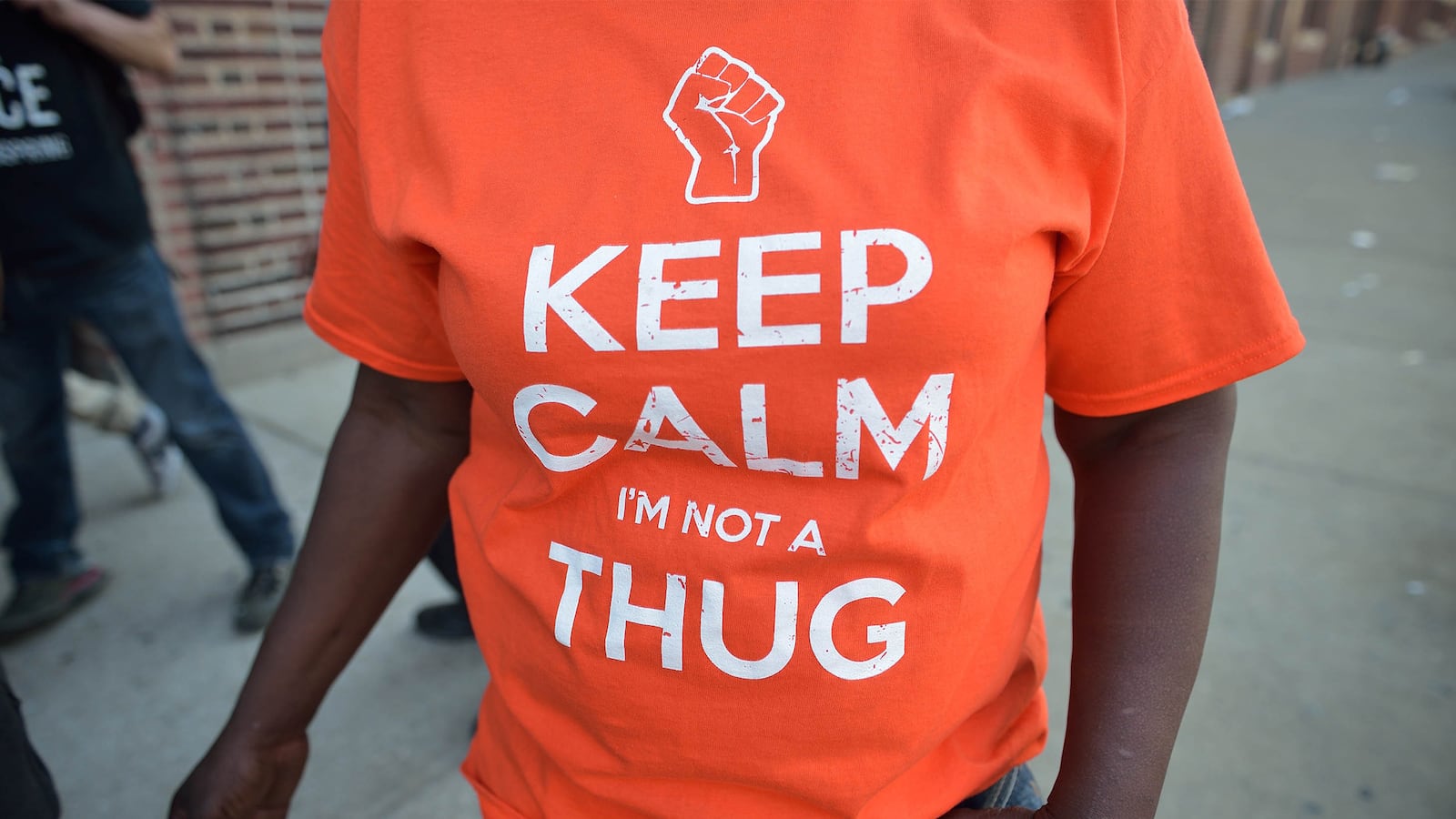

Why does it matter? Because so many of the men and women of West Baltimore and neighborhoods like it have almost no say in who represents them and what laws affect them. From a public safety perspective, one study has found that ex-offenders on probation and parole were less likely to re-offend if they were able to vote, although more study is needed.

More important are the questions of fairness and citizenship. Perry Hopkins, a 54-year-old ex-offender who is now a community organizer in West Baltimore, told me he got the first voter registration card of his adult life last week. The first presidential election he will be able to vote in is 2016. “I can’t tell my kids that when we had our first African American president, I voted for him,” he said. “I had to witness history. I couldn’t be a part of it.”

The men he meets in West Baltimore often have little or no hope in their futures, and he believes letting them have more of a say in their city, state, and national governments could restore some of it. “Everybody needs to have a stake in the community, a stake in the country,” Hopkins says.