When Georgia Republicans signed a sweeping election overhaul into law in the spring of 2021, Democrats sounded the alarm over a number of provisions that they said would significantly suppress voter turnout.

But it turns out that one of the law’s least noticed changes—cutting the length of runoff election campaigns in half—could end up having the biggest impact on the outcome of the 2022 election in this battleground state.

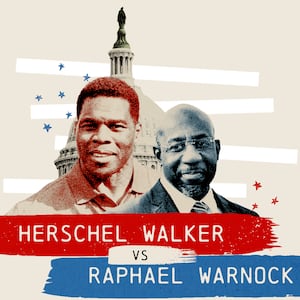

On Wednesday, multiple news outlets projected that the battle between Sen. Raphael Warnock (D-GA) and Republican candidate Herschel Walker would go to a runoff election, after both failed to surpass 50 percent of the vote in the general election.

But instead of a nine week runoff campaign—like in 2020, when Warnock and Sen. Jon Ossoff (D-GA) both defeated GOP incumbents and flipped the U.S. Senate—this showdown will last only four weeks, with Election Day on December 6.

Democrats see the GOP’s move to slash the runoff campaign as a tactic to prevent a repeat of their 2020 losses. The change, said Democratic state lawmaker Teri Anulewicz, is “going to have the most tangible impact on what happens with Georgia’s Senate delegation” than any other element of the GOP’s new voting law.

Not only will the runoff reforms shape the parameters of the battle between Warnock and Walker, the new rules could help determine which party controls the U.S. Senate. As of Wednesday afternoon, if Republicans and Democrats split the two uncalled races—in Arizona and Nevada—then the Senate majority will rest on Georgia.

For Democrats, one of the most concerning changes to the runoff system has to do with voter registration. In 2020, 78,000 people registered to vote in the Senate runoff who were not registered to vote in the general election, following an intense drive from Democratic-aligned organizations to generate as much turnout as possible for the January 5 election.

In 2022, new voters won’t be a factor at all. Under the GOP voting law, the deadline to register for the runoff was the day before the general election. Given the narrow margins of the last election—Ossoff won by 55,000 votes—that change alone could prove “decisive,” said Charles Bullock, a longtime professor of politics at the University of Georgia.

Anulewicz said that so many new voters registered in the run-up to this year’s general election that it’s hard to say how much of an impact the runoff changes could have. “At the same time, when we’re talking about races this close, any potential impact can’t be understated,” she told The Daily Beast.

Beyond voter registration, the newly abbreviated runoff timeline means that people who vote by mail—a largely Democratic group—will have less time to return those ballots. In 2020, absentee ballots began going out to voters about two weeks after Election Day, and then voters had some six weeks to mail them back. The turnaround will be much tighter this time around, even if ballots are mailed out quickly.

A shorter runoff period also means fewer days of in-person early voting. In 2020, voters could cast their ballot that way over a three-week period. Now, the in-person early voting period will only last for five days. Fair Fight, the voting rights group founded by Stacey Abrams, estimated that 1.38 million Georgia voters, roughly one-third of the runoff electorate, cast their votes during the weeks that were later cut from the campaign.

In the aftermath of Warnock and Ossoff’s upset victories in January 2021, Republicans were furious, and some immediately called for changes to the runoff election structure. Ironically, Georgia’s runoff structure has historically helped keep Republicans in power. Before 2020, Democrats performed worse in the runoff than in the general election all but once in the nine previous runoffs, with Black turnout tending to drop significantly.

After the June primary, Georgia elections officials had their first taste of dealing with the shortened runoff period, and some publicly vented that it did not give them enough time to administer another election. Even supporters of SB 202 acknowledged that administering the election in such a tight timeframe was challenging.

The way counties administered the new rules also gave Democrats and voting rights advocates concerns about voter access. For example, SB 202 allows counties to allow early in-person voting as soon as they can, but only 10 of Georgia’s 159 counties did so before the mandatory deadline.

With potential control of the Senate on the line, Democrats remain concerned about the new structure of the runoff. But the party’s strong voter turnout even given other restrictions under SB 202 makes Anulewicz optimistic.

“Having the shorter runoff period is a challenge,” she said, “but I think that, looking at the numbers, it seems we’ve demonstrated an ability to overcome challenges.”