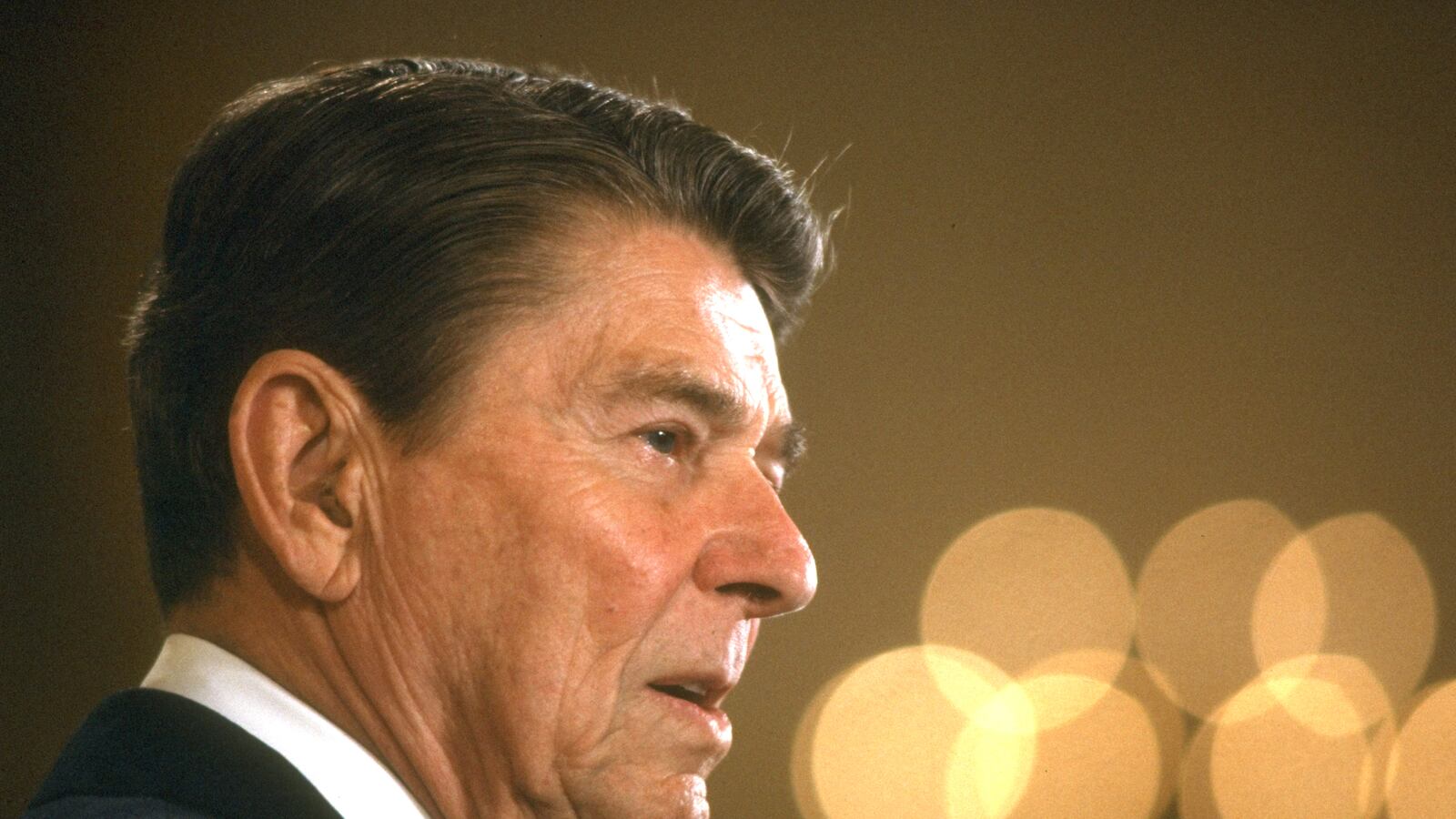

It was a Republican-led U.S. Senate that stood up and defied President Reagan in October 1986, voting to override his veto of a sanctions bill that had passed both House and Senate with bipartisan support. Despite aggressive lobbying by the White House, 31 Republicans joined all 47 Democrats for a final tally of 78 to 21, 12 more than the two-thirds needed and a significant blow to Reagan, the first president in the 20th century to have a veto overturned on a matter of foreign policy.

That his own party delivered the winning votes added insult to injury for Reagan, who was two years into his second term. “The veto [override] was a political symbol that things were changing very dramatically and that accommodation had to be made,” says Edward Djerejian, a former ambassador to Syria and Israel who worked alongside chief of staff and then secretary of state James Baker on foreign policy in the Reagan administration.

It’s hard to comprehend today, when partisanship in Congress seems to trump everything, but in Reagan’s time, on foreign policy both parties generally adhered to the belief that “politics ends at the water’s edge,” a phrase coined by Sen. Arthur Vandenberg (R-MI), chairman of the Foreign Relations committee in the late 1940s, defending the bipartisan consensus he achieved with President Truman.

Reagan is lionized by conservatives today, who credit him with moving the GOP to the right. The party Reagan headed in the ’80s had a lot more moderate to liberal senators, including William Cohen of Maine, who would serve as defense secretary in the Clinton administration, Richard Lugar of Indiana, defeated last year by a Tea Party challenger, even Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, then a freshman, who explained his vote to override Reagan’s veto this way: “In the 1960s, when I was in college, civil rights issues were clear,” he said. “After that, it became complicated with questions of quotas and other matters that split people of good will. When the apartheid issues came along, it made civil rights black and white again. It was not complicated.”

Republican Nancy Kassebaum of Kansas was one of only two women in the Senate at the time. She chaired the subcommittee on Africa and as a legacy Republican, the daughter of Alf Landon, the 1936 Republican nominee against FDR, her pedigree and her quiet intelligence carried moral authority. The Kansas City Star had likened her to an “injured wren” when she stepped into her first race in 1978, but she proved herself a relentless inquisitor when needed, becoming one of the first in her party to push publicly for sanctions against the apartheid regime.

Six Republicans who initially supported sanctions switched their votes under White House pressure. They included former Senate majority leader Bob Dole and Sens. Orrin Hatch of Utah and Thad Cochran of Mississippi, who are still in the Senate today.

Reagan actively lobbied, taking to the airwaves to deliver a speech on the importance of rejecting sanctions and calling members individually to make his case. One of his favorite arguments was that more blacks in South Africa owned cars than there were cars in the Soviet Union, proof in his mind of the evils of communism. The administration’s policy was grounded in the Cold War view that the all-white government in Pretoria was a bulwark against communism. “He was very attached to the policy of constructive engagement. He believed in it,” says Djerejian.

Even before the Iran-Contra scandal tarnished Reagan’s second term, he was leaking political capital, says Jack Pitney, professor of American politics at Claremont-McKenna College. With the exception of tax reform, the president didn’t have much of an agenda, and public opinion was changing on South Africa. “Members of the Senate were reading the polls,” says Pitney. “No one realized in 1986 how rapidly the Soviet Union would fold, but the Cold War was coming to a close.”

That November, the Republicans lost the majority in the Senate they had held since Reagan’s election in 1980. Weaker senators elected on Reagan’s coattails were swept out, among them Paula Hawkins of Florida and Jeremiah Denton of Alabama, a former prisoner of war. The tax overhaul the White House thought would be a winner at the polls turned out to be a wash, while a 1985 vote on Social Security left an indelible impression with voters. Democrats wheeled in California Sen. Pete Wilson on a stretcher the day after his emergency appendectomy to vote against the measure. Reagan’s reform package, which cut benefits, passed 50 to 49, with Vice President George H.W. Bush breaking the tie, a result that made House Republicans nervous. They bailed, leaving Senate Republicans to defend a damaging vote that would cost them their majority.

Even so, there were more profiles in courage then in both parties than we see today. Reactionaries such as North Carolina’s Jesse Helms and South Carolina’s Strom Thurmond commanded their share of headlines, but more often than not they were seen as caricatures, “holdovers from the days of segregation, so they represented a political generation that was fading into the past,” says Pitney, assigned then as a congressional fellow in the office of Sen. Al D’Amato (R-NY). “He is remembered for other things,” says Pitney of his former boss, “Senator Pothole,” a master of political stunts who when waging a filibuster once read the D.C. phonebook. There was lots of conservative bluster, “but his voting record was moderate to liberal,” says Pitney. D’Amato was among the Republicans who defied Reagan.