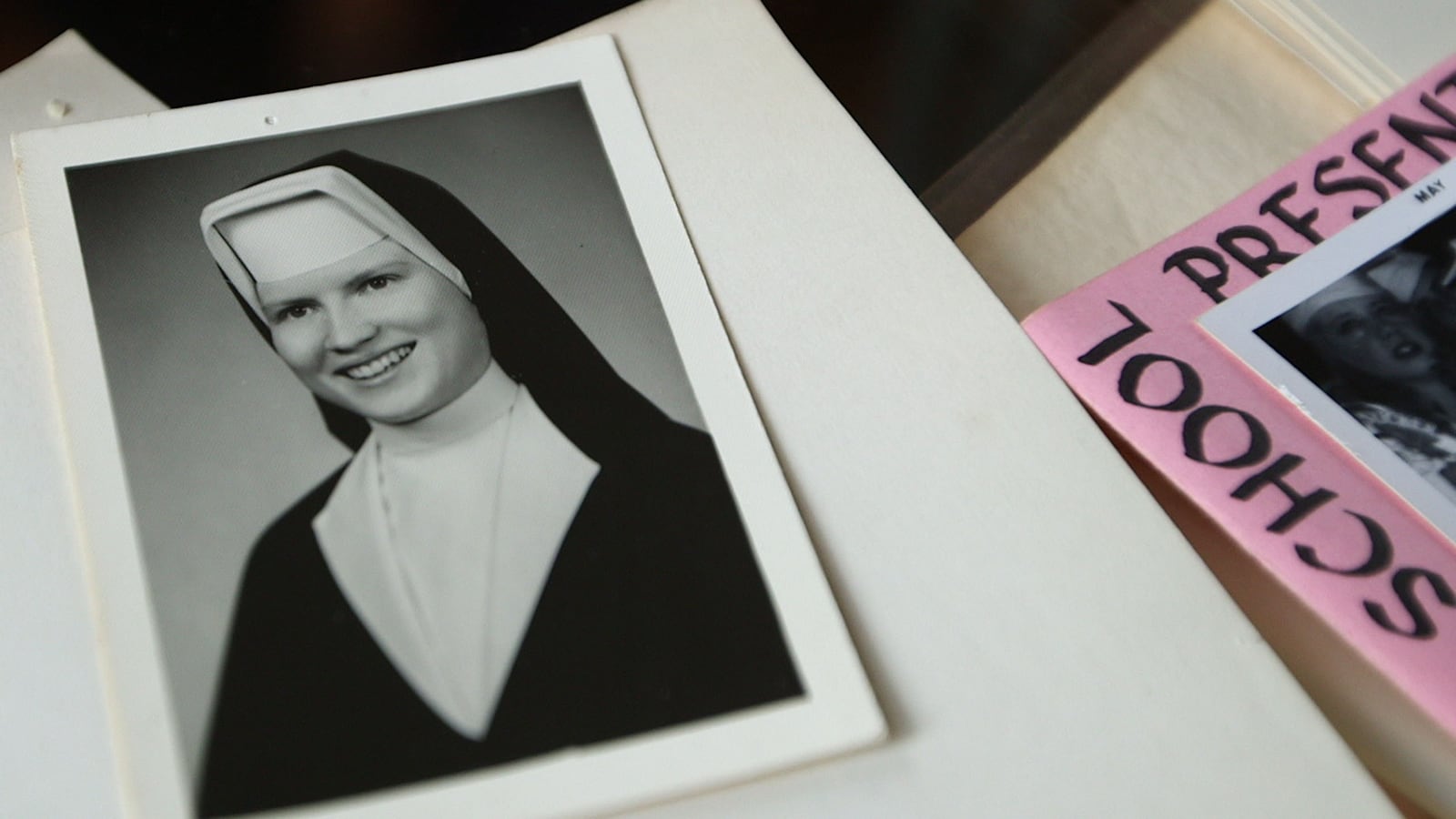

On Nov. 7, 1969, Sister Cathy Cesnik, a 26-year-old Catholic nun, vanished under what were immediately suspicious circumstances. Having recently left her job at the all-girls Keough High School in Baltimore in order to teach at a public high school alongside roommate Sister Russell Phillips, Cesnik departed her apartment on the night in question around 6:30 p.m. to go to the Edmondson Village shopping center to cash a paycheck, pick up some buns at the bakery, and buy an engagement present for her younger sister Marilyn. Hours later, her car was found—parked at an odd angle, a block away from her residence. There was mud on its tires, a twig near its steering wheel, and no signs of Sister Cathy. It would be two long months before her body was found at a remote garbage dump near Lansdowne.

The mystery of who killed Sister Cathy—a crime followed by the murder of a neighboring Catholic girl named Joyce Malecki—is the hook of The Keepers, Netflix’s new seven-episode series, premiering this Friday, May 19.

Following in the footsteps of Making a Murderer, HBO’s The Jinx, and the granddaddy of such true-crime investigations, Errol Morris’ 1988 documentary The Thin Blue Line, Ryan White’s multi-part documentary is, in one sense, an act of cinematic sleuthing, aimed at solving a cold case through rigorous reexamination of evidence and suspects. Yet what differentiates it from its ancestors is that the secrets it uncovers have to do with far more than a simple homicide. That’s because what White exposes, with heartrending clarity and empathy, is an honest-to-goodness conspiracy involving sexual abuse and the Catholic Church. It’s Spotlight redux, albeit with far fewer heroes, far more horror, and far too many unanswered questions.

Using archival photos, maps, dramatic recreations and interviews, The Keepers’ first episode sets the scene of Cathy’s disappearance in exacting detail. At the heart of this intro are Gemma Hoskins and Abbie Shaub, two Keough alums who adored Sister Cathy (a modern free spirit far removed from her elderly nun compatriots), and who are now determined to spearhead a social-media-enabled inquiry into what really happened to their former teacher. They’re amateur Nancy Drews, one the people person and the other the heavy-duty researcher, and both driven out of sheer altruism to figure out a mystery that’s plagued them their entire lives—as well as the lives of many others, including Sister Cathy’s clandestine boyfriend, Father Gerard Koob, and freelance journalist Tom Nugent, whose 6,000-word article about the case provides de facto narration in the early going.

It’s not until its second episode that The Keepers reveals its true scope. In 1994, a woman known only as “Jane Doe” came forward in the press to claim that, while she was a student at Keough, she had been the victim of terrible abuse at the hands of Father Joseph Maskell. And not just a casual victim: an innocent teenager who was perpetually molested, raped, and psychologically threatened and tormented by this man of the cloth and the numerous cops, businessmen, and other local leaders he allowed to assault her, in his own office and under his watchful eye. Moreover, “Jane Doe” asserted that Maskell had taken her to see the body of Sister Cathy, who—it turns out—had been approached by victims of Maskell about what was going on in the priest’s office. The implication is hard to miss, or dismiss: Sister Cathy was killed by Maskell (or someone working for him) before she could unmask him as a pedophilic monster.

“Jane Doe,” it turns out, is Jean Hargadon Wehner, and her saga is ultimately the heart and soul of The Keepers, whose whodunit detective work gradually comes to coexist side-by-side with a more expansive depiction of the immoral depths to which the Catholic Church has gone—and continues to go—to cover up its members’ atrocities.

In one horrifying account after another from Jean as well as Teresa Lancaster, a classmate who sued the Catholic Church as the “Jane Roe” to Jean’s “Jane Doe” in 1994, White plumbs an almost unfathomable well of depravity. Women forced to debase themselves via sickening acts that were cast in pious terms by (supposedly) holy perpetrators. Vile threats to family and loved ones. And most egregious of all (which is truly saying something), a concerted effort by the church to close ranks around its heinous clergymen and discredit anyone who dared speak out about their conduct.

The Keepers’ saga is far from a straightforward affair, thanks to all manner of complicating elements. Jean’s accusations come about after the re-emergence of her traumatic repressed memories, which leads certain people to call them into question. Gemma and Abbie pinpoint multiple suspects in the slaying of Sister Cathy, including Koob and two unrelated men whose respective nieces divulge shockingly similar stories about their possible culpability. Vital police records and evidence (including Maskell’s personal files, which he buried in a cemetery!) are missing or unavailable. Sharon May, head of the sex-abuse unit in the State’s Attorney’s Office, has unsatisfactory explanations for why Maskell was never prosecuted. The archdiocese comes after Jean and Teresa while refusing to answer questions on camera. Perhaps most problematic of all, most key players in this affair have long since passed away, making it next to impossible to corroborate various theories.

Throughout, White exhibits a firm grip on his convoluted multi-strand narrative. He clearly lays out the sordid network (church, government, business, law enforcement) that colluded on perpetrating such offenses, replete with the church moving Maskell from one post to another, to shield him from suspicion and prosecution. All the while, the director never loses sight of the complex—and almost unthinkable—ordeal suffered by Jean and Teresa as both kids and adults, not to mention the agony experienced by their spouses and children. “You see what happens when you say bad things about people?” Maskell told Jean after showing her Cathy’s body, as a means of scaring her into both silence and submission.

Yet as demonstrated by the fact that Baltimore detectives just exhumed Maskell’s body in order to obtain DNA evidence ahead of the Netflix show’s premiere, The Keepers is gripping and heartening proof that, in the quest for justice, there’s no greater virtue than people (and series such as this) asking difficult and courageous questions about very bad people.