When Amir Ramses decided to shoot a documentary about the history of Egypt’s rapidly dwindling Jewish community, the filmmaker knew he could be stirring up a hornet’s nest.

“People in Egypt have conspiracy theories about Jews,” Ramses told The Daily Beast in Cairo this week. “When you say the word ‘Jew,’ people automatically relate it to Israel.”

Problems began earlier this month when Egypt’s Censorship Bureau, which operates under the Ministry of Culture, told Ramses it would not be issuing a permit to allow the film to be released. Speaking shortly afterward, censorship chief Abdel Sattar Fathy explained to a local newspaper that the film had been marked up by State Security as unsuitable for public showing.

But following an outcry from free-speech advocates and fellow filmmakers, officials eventually backed down. And this week the documentary, which presents an unprecedented account of Jewish Egyptian life in the 20th century, finally went out on general release.

According to 33-year-old Ramses, the reaction from preview screenings he conducted before the film’s premiere was “weirdly positive.”

“We expected people to go into this kind of topic with hostile preconceptions,” he said. “But actually there was really good feedback.”

Rights groups and activists, although welcoming the eventual decision to issue a permit for Ramses’s documentary, criticized the earlier attempts by the nation’s deeply entrenched State Security services—weaned on anti-Zionist antipathy and reared under the shadow of successive wars with the Jewish state—to torpedo his film.

“It implies that the same laws used by the old regime are still being used by the current regime,” said Emad Mubarak, director of a free-speech NGO that had been helping Ramses prepare legal action against the Egyptian authorities.

The documentary, titled Jews of Egypt, certainly marks a daring watershed in Egyptian cinema.

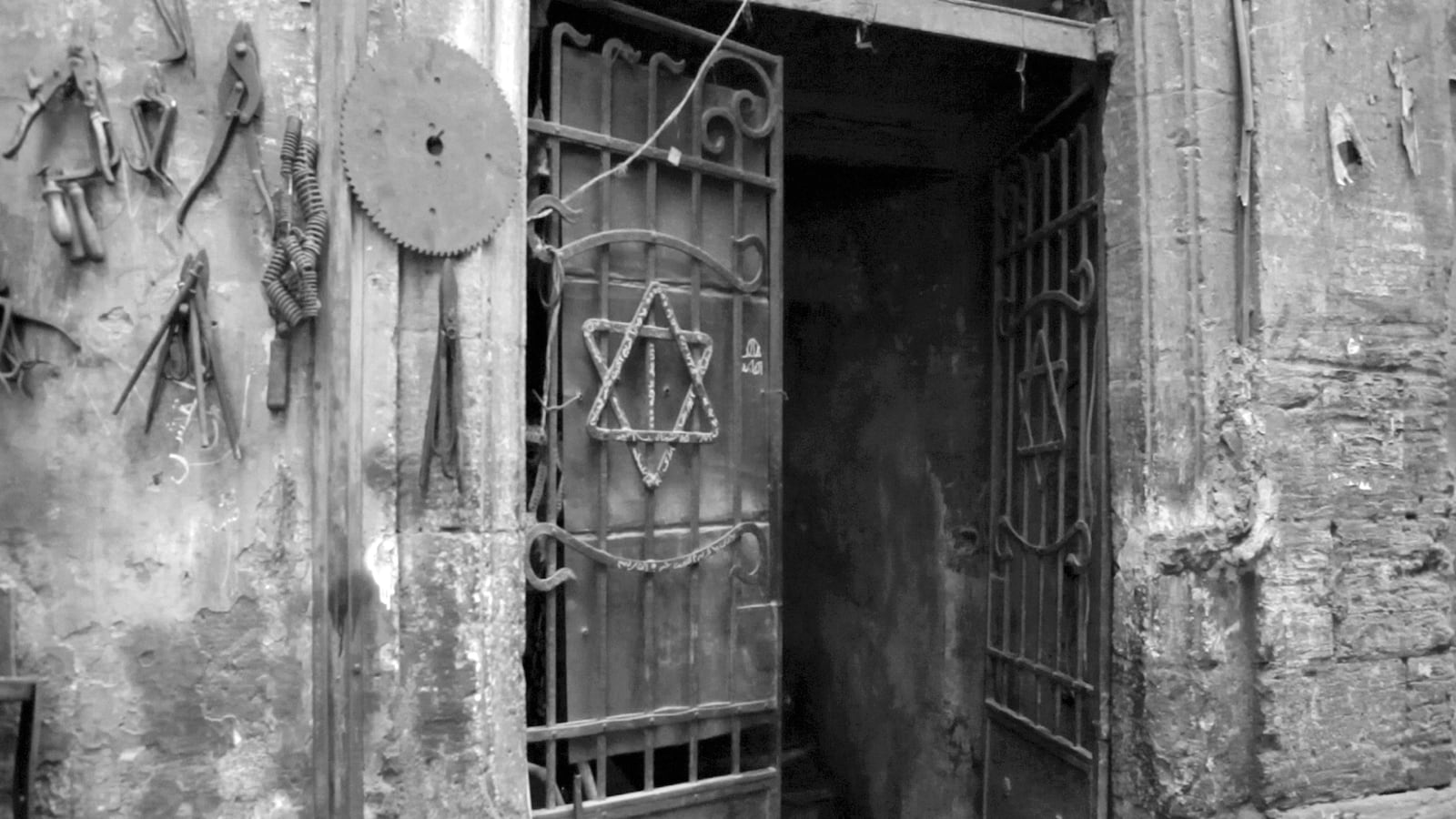

Described on its website as an attempt to find out why the country’s once-thriving Jewish community went from being “partners in the same country to enemies,” it represents the first time any serious attempt has been made to document the collective experience of Egypt’s 20th-century Jewry for a mainstream film.

Numbering up to 100,000 at their peak following the Second World War, the Jewish presence in Egypt stretches back more than 3000 years to the time of Ramses II.

Despite constituting only a fraction of the Egyptian population, many rose to positions of the highest prominence. The great medieval Jewish polymath Maimonides was at one time chief physician in the court of Saladin, the great Crusader foe of the English king, Richard Lionheart.

More recently, in the first half of the 20th century, King Fouad’s chief speechwriter was a Jew, as was his minister of finance.

Many who lived in Egypt during the twilight of Britain’s fading influence as a colonial power gaze back longingly to a cosmopolitan country where they say Italian and Greek merchants lived peacefully alongside their Jewish neighbors—albeit in a society where plurality was often underpinned by British bayonets.

Roger Biboul, an Egyptian Jew now living in the U.K. after being expelled from his homeland in the 1950s, told The Daily Beast that his childhood growing up in the Mediterranean city of Alexandria was a “glorious time.”

“It was a very multicultural environment where people from different religions and nationalities got on with each other,” said the 72-year-old. “We had a very nice, blessed type of existence.”

But problems began when Gamal Abdel Nasser took power in 1954. After a high-profile Israeli spy ring was uncovered that same year, popular attitudes against Jews hardened.

In the wake of the Suez Crisis of 1956, when Israel helped Britain and France invade Egypt to reclaim the Suez Canal, the government ordered a wave of expulsions. Over the following years, tens of thousands more left, joining the other foreigners who were fleeing Nasser’s nationalist revolution.

The current size of Egypt’s Jewish community now numbers no more than a few dozen.

The youngest member of the mostly female community is older than 50, while most of those who remain have married Muslim or Christian men, meaning that Egypt’s Jewish culture is likely to die out within the space of a generation.

“I think in Egypt you could question whether there is any future left in the Jewish community,” said Rabbi Andrew Baker, an American who has been trying to help establish a fund to preserve the country’s Jewish heritage.

Those who remain live in a society, that, over the years, has become steadily more hostile toward Israel—a hostility that occasionally bubbles over into outright anti-Semitism.

Although the Egyptian government has carried out high-profile restorations of synagogues over the years, members of the Egyptian Jewish Diaspora complain that officials often seem ambivalent about the projects.

In one telling scene from Jews of Egypt, an elderly man is filmed telling an interviewer how much he likes the famed Egyptian singer Leila Mourad. After being told that she was Jewish, he then changes his mind.

“I did this film because I’m very concerned about where we are going as a society,” said Ramses. “My utopia was Alexandria in the 1940s. But I feel a depression about where we are now.”