As the doomed Titanic began its final countdown before disappearing under the sea 107 years ago Monday, there was a last gasp of activity on the deck.

These scenes have become well known thanks to big-screen adaptations of the disaster: the rush to load the few remaining life boats with women and children, the brave musicians who took up their instruments for one last concert, the tilt of the deck as the ship began to tip into the ocean.

Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson knew these final moments all too well—he experienced them first hand. His life was saved at the last minute by a frantic leap into a nearby lifeboat as the Titanic began to sink, but 1,517 passengers and crew were not so lucky. Nor was his prized possession, an oil painting by the renowned 19th century French painter Merry-Joseph Blondel.

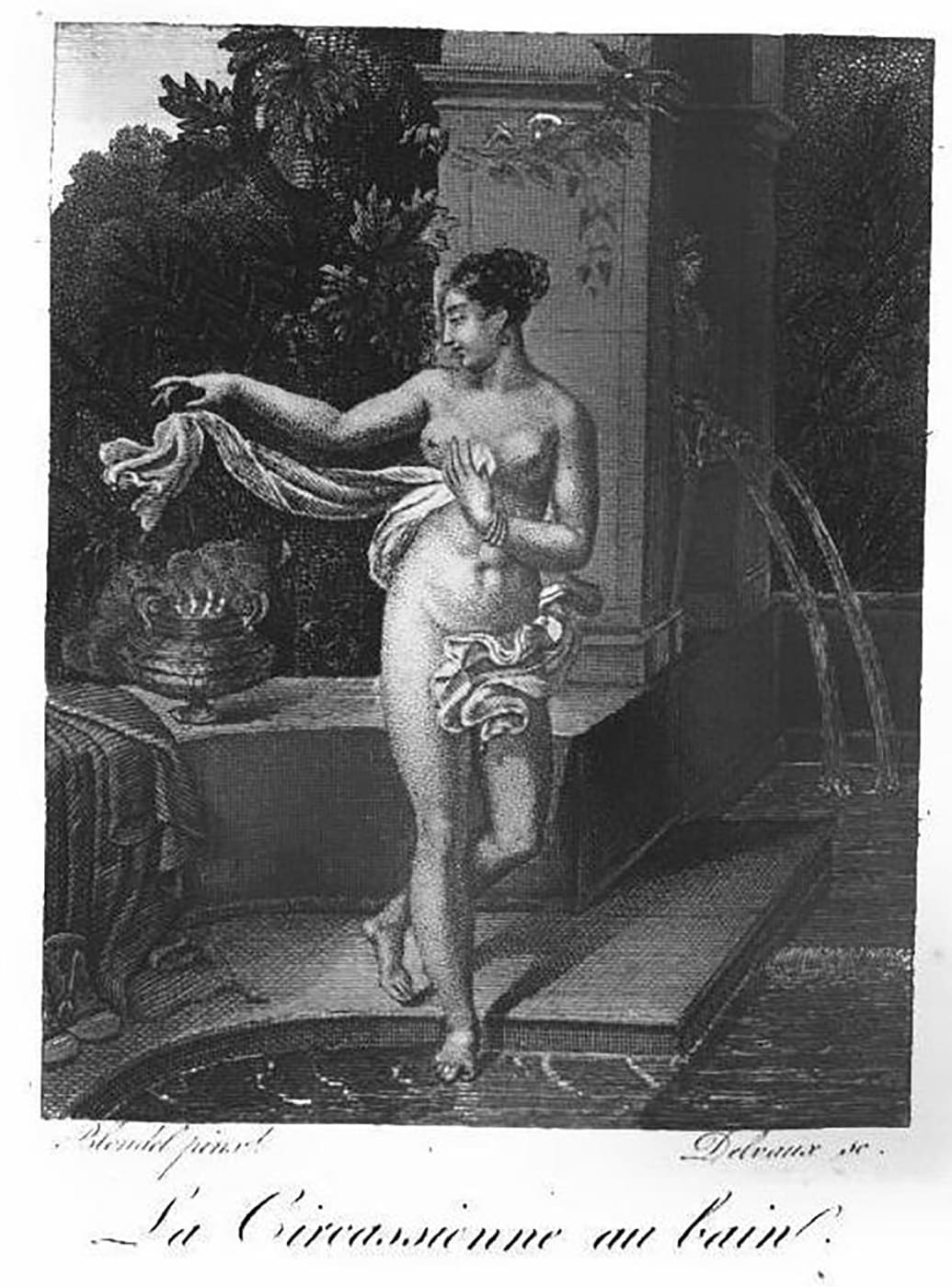

“La Circassienne au Bain,” also known in its early days as “Une Baigneuse,” made its debut at the Paris Salon of 1814 just as Blondel’s career was beginning to take off, though it took a few years before the critics warmed up to his bathing Circassian woman.

But in 1912, it reached its pinnacle of fame when it became the most expensive piece of property buried with the Ship of Dreams, at least according to the claims filed.

Starting in the late 17th century, the annual Paris Salon was the place for artists to exhibit their work in France. The state-sponsored Salons were where new artists were discovered, where established artists solidified their reputations, and where the public was invited to join in the cultural conversation.

Blondel would eventually become one of France’s esteemed neoclassical painters. Throughout his long career, he was the recipient of public art commissions that continue to decorate some of the most important buildings in France including the Louvre and the Palace of Versailles; he was awarded some of the top honors of his day, namely the Prix de Rome in 1803 (courtesy of Louis XVIII) and the Légion d’Honneur two decades later (with thanks to Charles X); and he was named to prestigious academic positions.

But early in his career, in 1814, he was surely delighted when four of his works were accepted for exhibition in the Louvre rooms at the annual Paris Salon. “La Circassienne au Bain” was among them.

Initially, the historical loss of this work on the Titanic was near total. Not only did the actual painting perish at sea, but there was little information left behind as to what it once looked like—few descriptions existed and there were no reproductions or photographs of the original, only one engraving.

But in the early 2010s, an artist working under the pseudonym “John Parker” conductive extensive research on Blondel’s lost work and created a reproduction of “La Circassienne au Bain” that was auctioned off by Plymouth Auction Rooms in 2016 for £2,700. (The artist did not respond to an interview request sent via the auction house, which also declined to comment for this piece.)

Parker’s reproduction shows a classical setting of an open-air bath in which Blondel painted a nude Circassian woman stepping into the water with one foot, the other balanced behind her resulting in a figure arranged in the traditional Greek contrapposto style.

The woman’s emerald green robe is thrown over the short concrete wall behind her. She looks off to the side towards it as her arm extends out, both showing off her figure and in a gesture to remove the remaining transparent silk scarf that provides her with just a touch of modesty.

Despite her nudity, the woman’s hair remains in an elaborately braided updo and her ears are garnished with appropriately dazzling baubles. Lush trees and foliage hover beyond the open walls of the bath.

When Blondel showed this work in 1814, he had only been back in France for a few years after his stint studying art in Italy. Three years later, he would win a gold medal at the Salon, but in 1814, at least one of the four paintings, the one that was doomed to a watery grave a century later, did not receive overwhelming praise.

“His design and color lack truth and finesse, and we can say nothing in favor of this work, except that it is executed by a very skillful artist in practice,” French artist and art critic François Séraphin Delpech wrote of “La Circassienne au Bain” in his review of works at that year’s Salon.

Delpech’s pronouncement was representative of the critical response to the piece: “meh.” But that allegedly changed a few years later after Blondel’s star had risen higher. When the public took a shine to the nude bather, the critics decided it wasn’t so bad after all. If not his most famous work, “La Circassienne au Bain” became well regarded.

Fast forward nearly a century and hopscotch a few European countries north, and Mauritz Håkan Björnström-Steffansson enters the tragic story of “La Circassienne au Bain.”

In 1912, Björnström-Steffansson was the 28-year-old son of a Swedish pulp baron, and he was preparing to travel to the U.S. to further his studies. As was only natural for a prominent young lad in that year, he had secured passage on the inaugural voyage of the Titanic, the ship being hailed as the largest and grandest to ever sail the seas.

Before he left, Björnström-Steffansson purchased a masterpiece—the famed French painter Merry-Joseph Blondel’s early work “La Circassienne au Bain”—to take with him.

What drew him to this piece, what he paid for it, or why he decided to purchase it before traveling to America to start a new life is unknown. What is known is that when Björnström-Steffansson boarded the Titanic on a first-class ticket, the Blondel was with him.

During the early days of the voyage, Björnström-Steffansson fell in with a group of other first-class passengers including the English businessman Hugh Woolner. It is from the testimony of Woolner during a U.S. congressional inquiry into the disaster that we know the details of what Björnström-Steffansson experienced on that fateful night.

On the evening of April 14, Woolner and Björnström-Steffansson were in the smoking room when the Titanic struck an iceberg. “We felt a sort of stopping, a sort of, not exactly shock, but a sort of slowing down; and then we sort of felt a rip that gave a sort of a slight twist to the whole room,” Woolner testified.

After retrieving life jackets from their respective quarters, Woolner said the two men met up back on deck and began assisting women and children into the lifeboats. They also came to the aid of First Officer Murdoch when a group of men tried to swarm one of the starboard-side boats.

When most of the boats had been filled and dispatched, the two friends decided to go to the A deck one story below to make sure all of the passengers had evacuated to higher quarters. Woolner said it was completely empty of people.

“It was absolutely deserted, and the electric lights along the ceiling of A deck were beginning to turn red, just a glow, a red sort of glow. So I said to Steffanson [sic]: ‘This is getting rather a tight corner. I do not like being inside these closed windows. Let us go out through the door at the end.’ And as we went out through the door the sea came in onto the deck at our feet.”

Woolner testified that they then went out onto the gunwale to prepare to dive into the ocean to escape being drowned in the enclosed A deck.

Once outside, they happened to notice that one of the last lifeboats was still being lowered into the water. There was a little bit of room left in the boat, so the men decided to make a jump for it. (The authors of On a Sea of Glass note that the duo probably knew that this boat was still making its way to the sea when they went downstairs, and also that jumping into it from below would be their only shot at survival.)

“[Björnström-Steffansson] jumped out and tumbled in head over heels into the bow, and I jumped too, and hit the gunwale with my chest, which had on this life preserver, of course and I sort of bounced off the gunwale and caught the gunwale with my fingers, and slipped off backwards.”

By the time they were both safely inside, the Titanic was rapidly sinking. The lifeboat was quickly paddled away from the doomed ship, and Woolner estimated they were about 150 yards out when the Titanic disappeared under the water. Both men were saved.

Nearly a year after the Titanic sank in the early hours of April 15, 1912, The New York Times reported that claims for more than $6 million had been filed against the White Star Line for loss of life, personal injury, and loss of property. In the later category, there were claims for jewelry, rare books, cars, a set of bagpipes, and a signed picture of Garibaldi.

But the most expensive claim of all was by Björnström-Steffansson who requested $100,000 (or the equivalent of over $2 million today) in compensation for the drowning of “La Circassienne au Bain.”

It’s unclear how much money Björnström-Steffansson received. In the end, White Star settled all of the claims for a total of only $664,000.

There was one bright spot for the Swedish businessman, who ended up making the U.S. his home.

Five years after the sinking of the Titanic, he married a woman to whom he was introduced by a fellow Titanic passenger, one he and Woolner had helped to save. The Björnström-Steffanssons remained married for the rest of their long lives.