What is it with Iran? I’m speaking, of course, about its role at the vanguard of postmodern cinema.

Just take measure of its masters: Abbas Kiarostami, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and Jafar Panahi. Their films’ bare, neorealistic adornments are only matched by the intricacies of their conjuring, with some springing free of labels as half-documentaries and half-illusions (Close-Up, A Moment of Innocence, This Is Not a Film, Ten, Hello Cinema), some with narratives, characters, and time that fold upon themselves (Gabbeh, The White Balloon, Through the Olive Trees, Certified Copy), while some are spare studies surrounding one conceit that opens out to include much of politics (and political critique) and life (Taste of Cherry, The Mirror, The Circle, Where Is the Friend’s Home?, Life, and Nothing More…), and almost all are about the subject of filmmaking (Shirin, Once Upon a Time, Cinema, Actor). Where did these great movies come from? Was Kiarostami the decisive figure, or did the country’s oppressive regime help fire the imaginations of world-class talents?

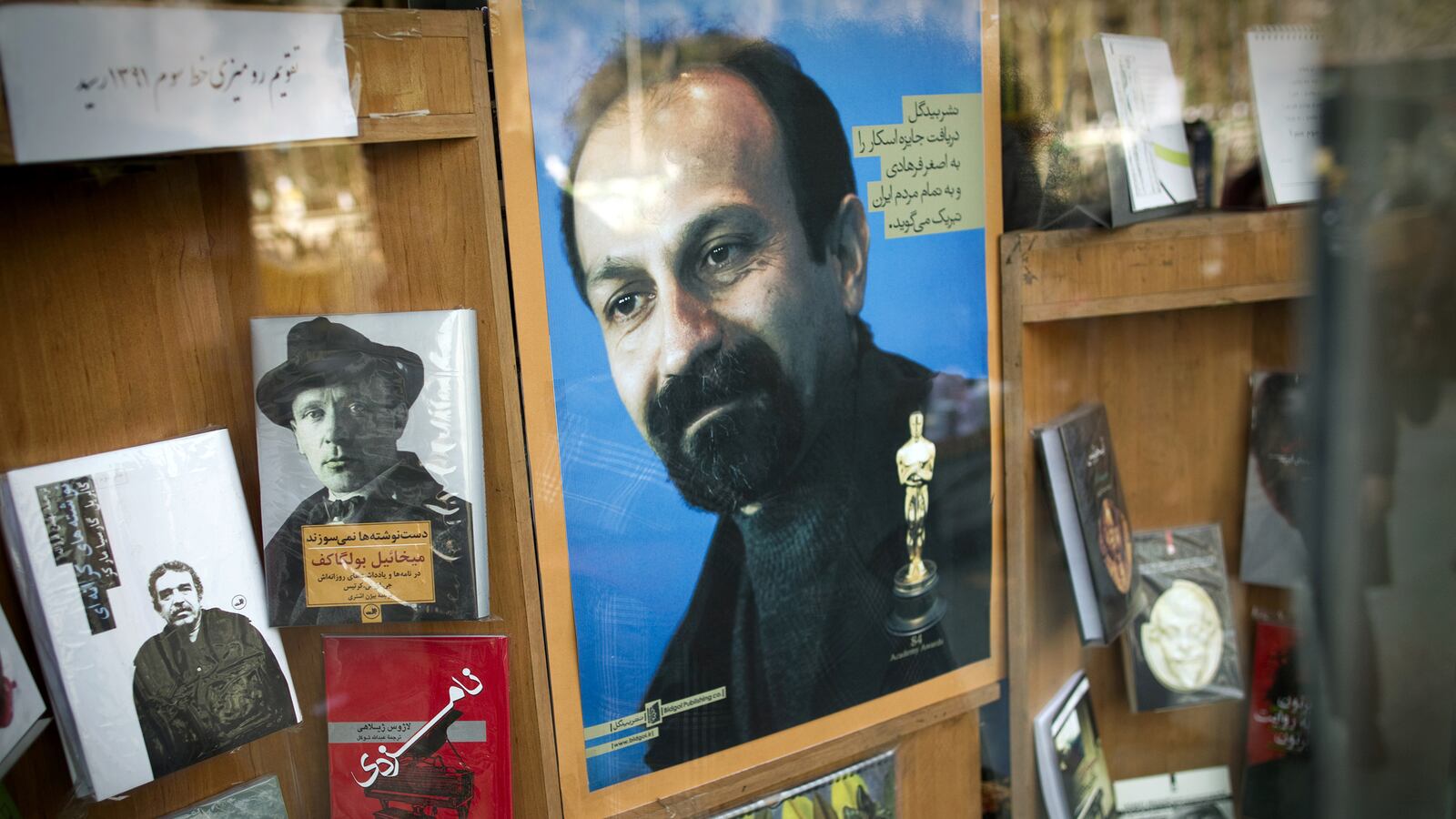

Whatever the answer is, change is underway. With Kiarostami working overseas, Makhmalbaf in exile, and Panahi under house arrest, the improbable figure of Asghar Farhadi has appeared to come to save the day. Improbable, yes, because Farhadi’s searching, earnest affairs about family and relationships buck the trend. There’s no trickery in his works, and he rarely bothers with overt political statements. But with 2009’s About Elly, 2011’s A Separation, and now, The Past, Farhadi’s explorations of moral dilemmas and airing of family grievances hint at a departure from Kiarostamian narrative playfulness. He has little ties to Kiarostami and his followers, and he hasn’t ventured into documentaries. He deals in melodramas, but lifts them into a higher plain, and they end up structurally controlled and gorgeous. Last week, The Past failed to make the shortlist for the Academy Award for best foreign film, which A Separation won in 2012. There was only a slim chance that Farhadi would be honored again so soon, but The Past is not an inferior film, whereas it even expands upon the formalistic beauty of its predecessor.

The form of The Past happens to be circular, and Farhadi opens with a woman calling out to a man—but he can’t hear her. The woman is Marie, played by Bérénice Bejo—or, if you prefer, the at last colored-in leading lady from The Artist. She’s at the Paris airport to pick up her ex-husband, Ahmad—and yes, they’ve already undergone a separation. But Marie’s asked him to return to Paris from Iran so they can obtain an official divorce. Ahmad finally notices her through the glass that separates them, and they scramble into the car while thunder and rain pour on them. As they go on their way, the windshield wipers screech away the film’s title, and if you’re familiar with A Separation, you’ll know to brace yourself and sit tight, in trepidation. Just when you think that the divorce will be the central battle to be fought over, Farhadi pretty much closes the book on the matter by the half-hour mark. As writer Sebastian Faulks said about reading a Penelope Fitzgerald novel, the experience is like being taken for a ride in a top-quality car, only to find that after a mile or so, “someone throws the steering wheel out of the window.” Welcome to a Farhadi domestic drama.

What’s left for the film to resolve? Everything else. First, there is the matter of whether Ahmad should really be staying at Marie’s cramped little maze of a house in the Paris suburbs during his visit. Anyone could have shouted, “Are you joking?” at the estranged couple, but the matter is once again left up to poor communication over a few botched emails. Then there is the small problem that Marie has failed to tell Ahmad that her boyfriend, Samir, has also moved in, along with his son Fouad. Before you know it a mini crisis breaks out over where Fouad is to sleep while Ahmad is visiting, and the long-suffering boy screams about wanting to go home. Ahmad tries to calm him down, and if the urgent messes had stopped there, The Past would resemble something like one of John Updike’s Maples stories. No luck there.

That’s because while Marie’s youngest daughter, Lea, loves having Fouad around as a playmate, the elder daughter, Lucie, a teenager, finds the idea of her mother marrying Samir nonnegotiable. Exactly why this is we don’t know, and Ahmad has been tasked to find out, which he does, sort of, after many twists and turns. Ahmad seems like the most sensible one at first, which is a nice gesture, since he’s played by Iranian actor and filmmaker Ali Mosaffa, the real husband to Leila Hatami, who played a similarly witting role in A Separation. He’s the outsider dropped into the middle of a web, but the lines of communication that he has to decipher are filled with so many secrets and obscured truths—often caused by missed phone calls, hacked emails, mistaken identities, as well as outright lies—that all he can do in the end is to go back outside, into the rain and back to Iran. Marie is on her own to navigate the fraught relationships she has with Lucie and Samir, and Bejo looks every bit as desperate as a woman who’s worn out by such demands would be. Oh, did I mention she’s pregnant?

On top of everything, there is Samir’s wife, who is in a coma. Everyone from Ahmad and Marie to Lucie are trying to figure out whether she ever found out about Samir and Marie’s affair. They all have a horrible secret to reveal, and The Past becomes a kind of whodunit filled with a series of devastating little aftershocks, much in the way that About Elly was. Samir pretends to not care, and as he is played by Tahar Rahim, looking even more wounded than he did in A Prophet, he again proves to be the one with oracular vision, knowing how ugly the truth can be and bewildered that nobody can see it. There’s been so much talk, but some things are better left unsaid.

Once more, as it was with A Separation, it is the children who hold the key to the adults. Just listen to Fouad and Lea’s assessment, as they roll their eyes and wonder whether the grownups can ever make up their minds about anything. Indeed, you might wish the plot were a little simpler, the feelings of everyone a little clearer, or that their frazzled nerves don’t come down to whether they are guilty for the state of a ghostly figure who’s haunting everything. But the miracle of Farhadi’s family dramas is their difficult journeys. The genre began with probing sonatas like Murnau’s Sunrise and Vigo’s L’Atalante, and reached its apotheosis with the saturated tearjerkers of Douglas Sirk. They were never so stylized after that, and although great performances would rescue some enterprises like Kramer vs. Kramer, melodramas have lately been awashed in either earnest or ironic homages to Sirk (The Ice Storm, American Beauty, Far From Heaven). How do you rescue a form from pastiche? As Marx said, history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. The third time, the past comes back as tragedy again, and what Farhadi has done is to take viewers on a knotty itinerary, only to bring them back home.

Hence the final shot of The Past, as you see Samir hold his comatose wife’s hand—silence, as with the first shot, but now the connection is transferred from one troubled couple to another. A man is reaching out to get through to a woman. Does he succeed? The film does not say, and it won’t provide you with relief. Nor should it—after all, we’re very much on our own. The past, Faulkner would say, is not dead. It’s not even past.