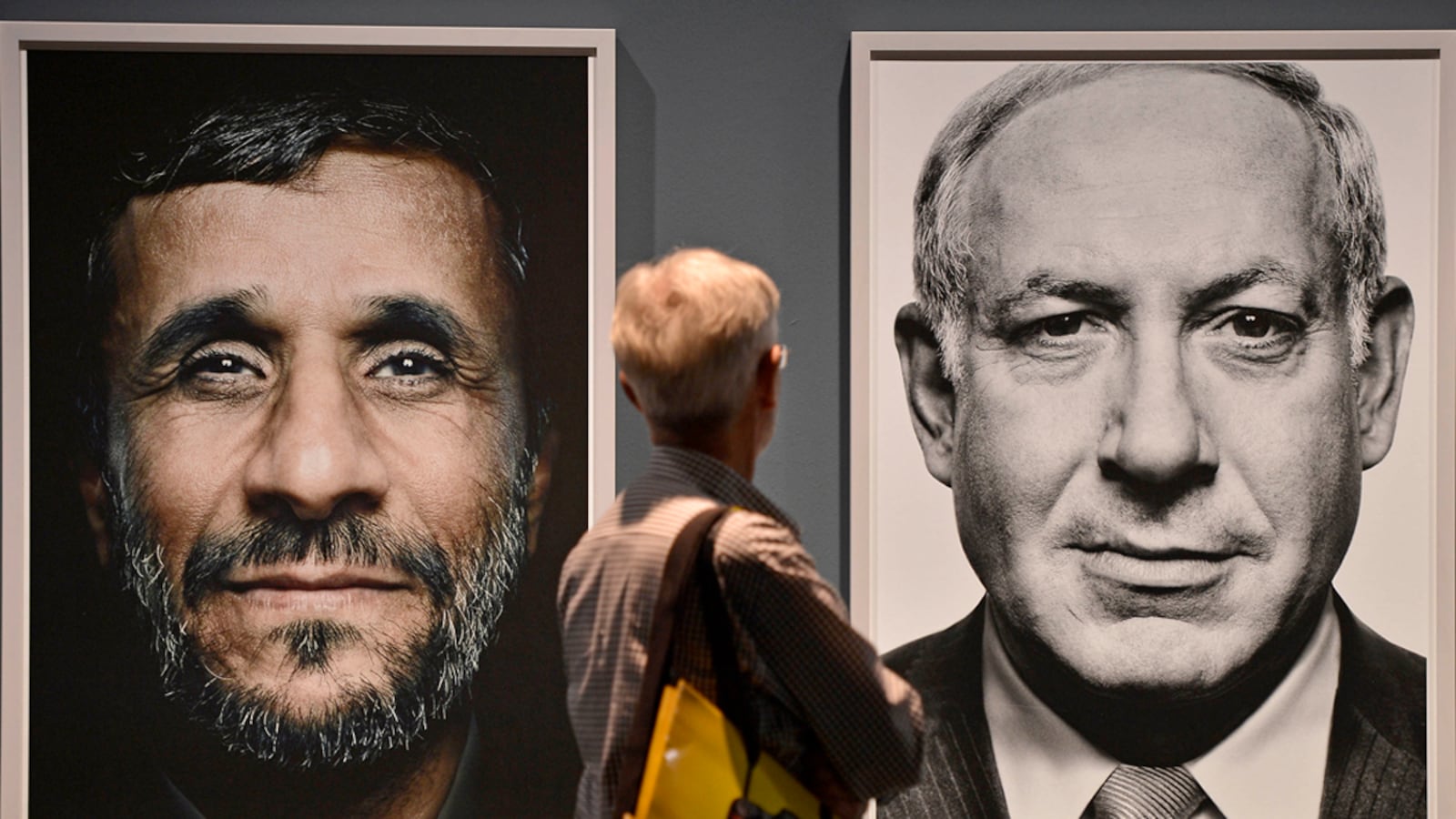

One of the most curious features of Israel's just-passed elections was the utter absence of the issue which for two years has dominated Israel's interactions with much of the outside world: Iran. Wrangling over the coalition only begins now, but already many see the second place party, Yair Lapid's Yesh Atid, joining the winner Benjamin Netanyahu's likely next government. That could bode well for mending fences with the U.S. over the issue of Iran—a point of much tension between Netanyahu and the recently re-inaugurated Barack Obama—but smoother cooperation doesn't necessarily mean Israel would be pushing any less of an aggressive line. That's especially true if the super-hawkish Naftali Bennett gets a hold of a foreign policy portfolio: Bennett's been even more confrontational with the U.S. on Iran than Netanyahu, and said on Fox News 11 months ago, "Over the next twelve months, the world has to act." He added, "How can we not do it?" One can almost hear the sighs of relief from the administration that Bennett didn't fare as well as expected at the polls. But the surprise star Lapid might come with his own baggage.

Unlike Netanyahu, who was and remains focused on Iran, Lapid mostly ignored the issue during the campaign. His most detailed invocation of Iran came in an October interview with the Jerusalem Post that was heavy on the criticisms but also hinted at some relatively important policy positions. For one, Lapid called for some deference—at least publicly—to the U.S. "Netanyahu made two big mistakes on the Iranian issue," Lapid said. "The first was instigating a conflict with the U.S. administration, betting on the wrong pony"—a reference to Netanyahu's nearly overt and much-criticized support for Mitt Romney. The result, Lapid said, was that Netanyahu squandered the attention he'd brought to the Iranian issue by making Israel a central player in what should be a global concern. In this vein, the rising centrist star blasted Netanyahu for trying to push the U.S. into war and threatening to launch his own prematurely: "It is hubris to give an ultimatum to the U.S. People tend to forget that the plane Netanyahu is sending to bomb Iran is an American plane," Lapid told the Post. "He thinks he can drag America to do what it doesn’t want to do. He is leading Israel to war too soon, before it’s necessary." This will sound familiar to those who think Netanyahu's been bluffing about an attack all along to spur the U.S. into harsher measures against Iran.

But for all his criticisms of Netanyahu on this front, Lapid was out of step with—and out front of—the U.S. In the Post interview, he called for regime change—"There is only one way to end the Iranian nuclear threat: the fall of the ayatollahs"—adding that more sanctions can accomplish this goal. Only that's not what the U.S. is after, in terms of policy aims: U.S. pressure is meant not to topple the government but to change Iran's nuclear behavior. That's why U.S. officials don't talk about regime change and instead speak of a diplomatic deal as the "best and most permanent way" to end the standoff. That encapsulates nicely a yawning gap between the views outlined by Lapid and the Obama administration, albeit not as great as that demonstrated by Netanyahu's overt pressure. Yesh Atid candidate Yaakov Peri, during the campaign, also hinted at these contradictions: "Concerning Iran, the U.S. should lead the military option, not Israel," he said. That tracks with Lapid: conciliatory to the U.S. but with precisely the hawkish overtones—regime change and attacking—that created rifts with Netanyahu in the first place.

Whether or not Lapid or another Yesh Atid candidate achieves a prestigious posting at the Foreign Ministry, the interplay between Israel and U.S. over Iran will be fascinating to watch. It seems most likely, especially given Yesh Atid's rise, that Netanyahu will maintain pressure but give up on his politically costly public confrontations with Obama. That should be welcome news for those hoping for a little space, despite Iran's recalcitrance, to forge a durable deal to avert the U.S. having launch a war that, as Lapid notes, it doesn't want to get into.