A Middle Eastern country covertly develops their nuclear program. Worried at the specter of losing its neighborhood nuclear monopoly, Israel pressures the U.S. to carry out a strike to destroy the nuclear reactor. When the U.S. balks, Israel goes it alone. And succeeds.

This is not the story of a future Israeli strike against Iran; this is Israel's attack on a Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007. This week in the New Yorker, David Makovsky leverages interviews with top Israeli and American officials to put together a granular account of the back and forth between Israel and the U.S. about what was happening at a suspected reactor site in the Syrian desert, and what to do about it. There is, however, an Iran connection: Makovsky tries to draw lessons for Iran from the Syria raid. But it doesn't pan out the way he might hope.

In Makovsky's story, he recounts a "key consideration" about whether to strike or not: the Israeli "desire to minimize the potential of a response from Damascus." The very secretiveness of the Syrian nuke program provided Israel an opportunity: if Syrian president Bashar al-Assad never had to directly confront the fact that he was doing covert nuclear work, he would not need to take a strong defensive posture against an attack. Assad has kept his borders with Israel quiet (like his father after the 1973 war)—an indication of not wanting a direct conflict with Israel. That meant if both Assad and Israel never acknowledged exactly what happened, things might not escalate.

Keeping a lid on the nuclear intelligence was essential, as was deniability for Israel:

Psychologists consulted by the I.D.F., who had profiled Assad for yeas, argued that Syrian retaliation might be avoided if Israel did not corner the President by publicly claiming credit for a strike, thus preserving what Israeli security officials called a "zone of denial."

Because the intelligence on the Syrian reactor was shared with the U.S., American officials too were asked to keep quiet about what happened in Syria. They acceded (over objections from Vice President Cheney).

The Israelis read it right, and the gambit paid off. Syrian officials, after the raid, gave various reasons for the giant explosion on their turf; none involved a successful Israeli raid or a nuclear facility.

"The pressing question today is whether the lessons of that success can be applied to Iran," Makovsky writes, going into a long, concluding section about Israeli positions and the potential threats posed by an Iranian nuke. But if the "desire to minimize the potential of a response" rested on providing Assad with a "zone of denial," then the only response to Makovsky's "pressing question" is a resounding "no": The lessons of the Israeli raid on Syria in 2007 can't be applied to Iran's nuclear program.

Unlike the Syrian nuclear program (or the Israeli one, for that matter), the Iranian nuclear program is not shrouded in complete secrecy. Far from a single reactor at a remote desert site, Iran has multiple nuclear facilities, all declared to U.N. authorities (the U.S. is "very confident that there is no secret site now," after past deceptions). How, then, if there were to be an explosion at a well known and declared nuclear facility, could the Iranians save face as Assad did? By pretending that they scared off the Israeli jets, who just happened to jettison their munitions on top of the Fordow enrichment facilities?

It's ironic, then, that the Israeli focus on Iran—constant pronouncements, threats, and public pressure on the U.S.—has driven the Iranian program into the spotlight, rendering moot the lesson of bombing Syria's secret program. Nonetheless, because the Israeli Syrian strike was a success, it will be held up as an example, just as proponents of war with Iran hold up Israel's 1981 attack on an Iraqi reactor as a success even though that claim doesn't hold up to scrutiny.

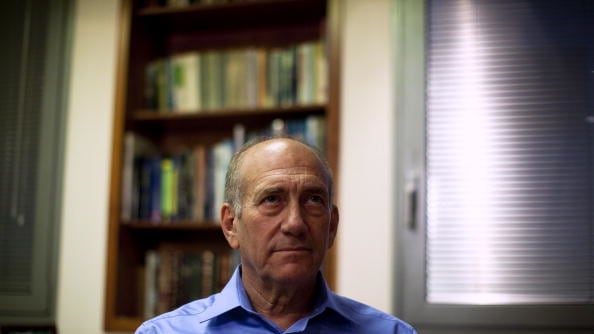

Former Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, whose government launched the Syria attack, hinted at this to Makovsky. "Each case must be examined separately," Olmert told him. "The Iraqi case was different from the Syrian case, and the Syrian case is different from the Iranian case." Like most of Israel's security chiefs, Olmert opposes an Israeli attack. Makovsky should definitely have listened more closely to him.