In the world of renewable energy, there’s perhaps no more ambitious goal than fusion power. This involves fusing hydrogen atoms to create helium—a process that generates an incredible amount of energy. It’s a reaction that occurs every single moment in the sun, but replicating it on Earth is a much more arduous process. If we succeed, however, we’ll have a clean source of renewable electricity that meets our ever-growing energy needs.

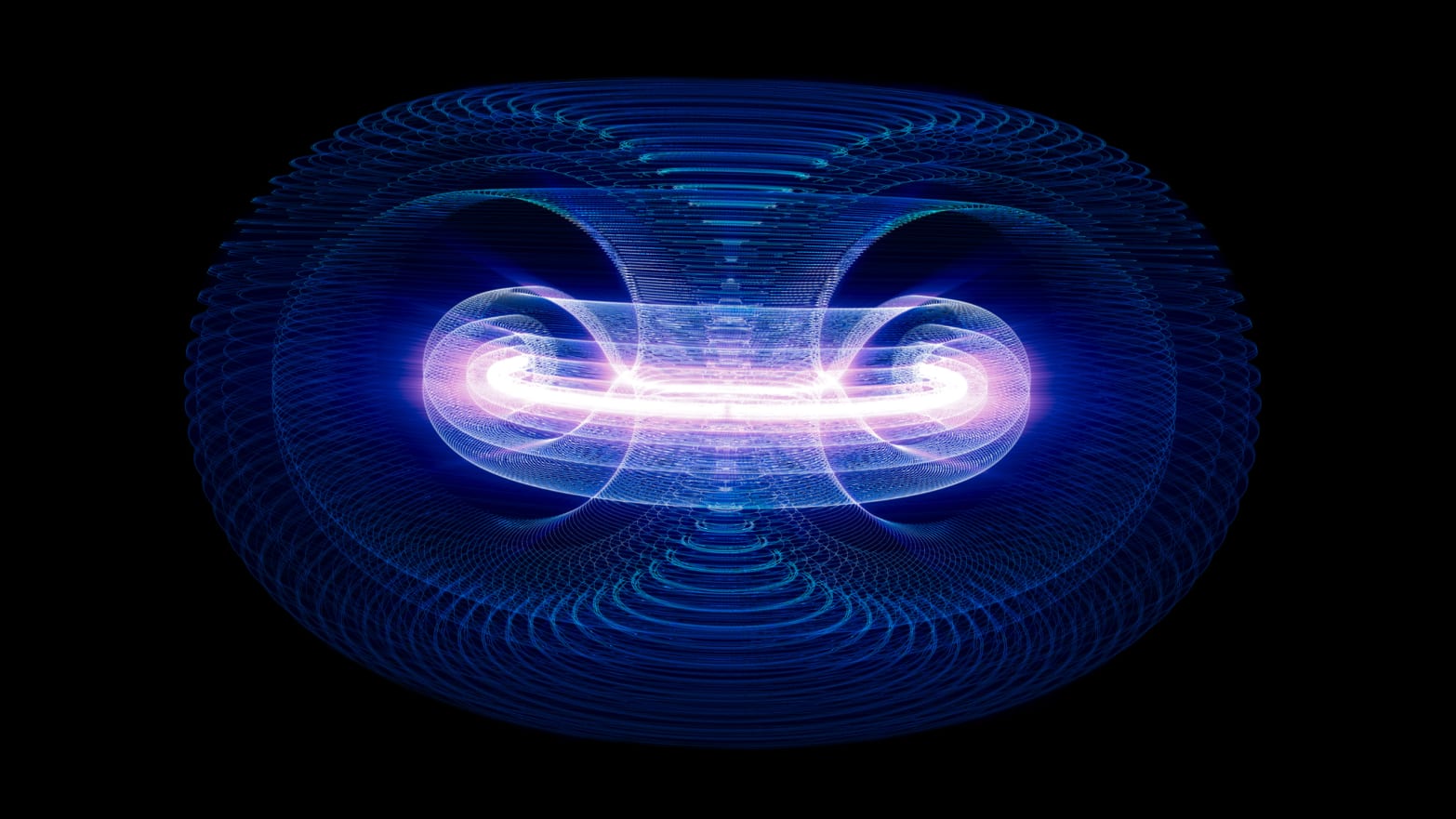

To that end, researchers are chasing after a phenomenon called “ignition,” which is when a fusion reactor generates more energy than was needed to create the initial reaction. A few major attempts are underway to achieve this goal, including the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) in France. That effort utilizes powerful magnets in a machine called a tokamak to create superheated plasma created using hydrogen fuel.

But therein lies an issue: There’s only so much hydrogen fuel you can put into a tokamak before everything starts going horribly wrong.

“One of the limitations in making plasma inside a tokamak is the amount of hydrogen fuel you can inject into it,” Paolo Ricci, a researcher at the Swiss Plasma Center, said in a press release. “Since the early days of fusion, we've known that if you try to increase the fuel density, at some point there would be what we call a ‘disruption’—basically you totally lose the confinement, and plasma goes wherever.”

To solve this issue, scientists began to research different equations to measure the maximum amount of hydrogen you can put inside of a tokamak before disruption. One law that eventually caught hold and became a mainstay in the fusion research world is known as the “Greenwald limit,” which says that the amount of fuel that can be used in a tokamak is directly correlated to the radius of the machine. The researchers behind ITER have even built their machine based on this law.

But even the Greenwald limit wasn’t perfect.

“The Greenwald limit is what we call an ‘empirical’ limit or law, which basically means that it’s like a rule-of-thumb based on observations made on past experiments,” Alex Zylstra, an experimental physicist at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, told The Daily Beast in an email. “These are very useful, but we always need to be cautious when applying them outside conditions where we have data from experiments.”

That’s why Ricci and his team have challenged this long-held belief in a new paper published on May 6 in the journal Physical Review Letters. In it, they posit that Greenwald’s limit can actually be raised—nearly doubling the amount of hydrogen fuel that can go into a tokamak in order to produce plasma. Their findings could lay the groundwork for future fusion reactors such as DEMO—a successor to ITER that’s currently in development—to finally reach ignition.

“This is important because it shows that the density that you can achieve in a tokamak increases with the power you need to run it,” Ricci said. “Actually, DEMO will operate at a much higher power than present tokamaks and ITER, which means that you can add more fuel density without limiting the output, in contrast to the Greenwald law. And that is very good news.”

Zylstra believes that the team’s finding is significant because it sheds light on why exactly fusion reactors have such a limit as well. It also shows that the designs for tokamaks like ITER or DEMO could be “less constrained than previously thought.” With the fuel density being increased two-fold, it could result in a vast improvement in their power output by tokamaks—and finally get us to ignition.

“Fusion is an extremely challenging problem—both scientifically and technologically, and making fusion power a reality requires many advances made one step at a time,” Zylstra added. “If this study is further validated, especially on machines like ITER, it will certainly help the magnetic fusion community credibly design and optimize future designs for experimental and power-generating facilities.”