They were supposed to be watching the prisoners, ensuring that the men stayed out of trouble while they did time for their crimes.

Instead, four guards at Rikers Island decided to commit a crime of their own. Their scheme would ultimately end in artistic tragedy—a Salvador Dalí painting presumed dead—but it was a surreal turn of events that the master himself may have appreciated.

The seeds for the guards’ demise was planted long before they took up their posts. In February 1965, Dalí was in New York City enjoying his annual winter residency at The St. Regis Hotel. When the artist first visited Manhattan in 1934, he instantly fell in love with the city. Room 1610 at the hotel would become his winter base for the next 40 years.

And who could blame him. By all accounts, he had the hotel and the city wrapped around his little finger. “Salvador Dalí adored turning this hotel into the stage of his celebrity, his one-man theatre, his private palace and zoo,” Adrian Dannatt wrote in the St. Regis Magazine.

He would announce his entrance on the premises with a loud shout of “Dalí is here!” and he would rule the place from that moment until his departure.

“Dalí always knew exactly what he wanted and he got it. The doormen had to pay Dalí’s taxi fare. He was ‘grand’ in the real meaning of the word,” said Jack Bond, director of the documentary Dalí in New York. “He fitted New York like a glove, it was made for him, and The St. Regis was, and still is, the best hotel in the whole city. He was even able to paint there – he kept a special room as his studio.”

It was there that a 60-year-old Dalí awoke on February 26, 1965, feeling a little under the weather. He was scheduled to visit Rikers Island that day to meet with inmate artists, along with his wife Gala, his pet ocelot Babou, and a whole gaggle of press (he never left home without them).

But the weather was chilly and he didn’t have it in him to make the scheduled boat ride out to the island, the only way to access the facility at the time. To make up for his cancellation, he sent the prisoners a custom gift.

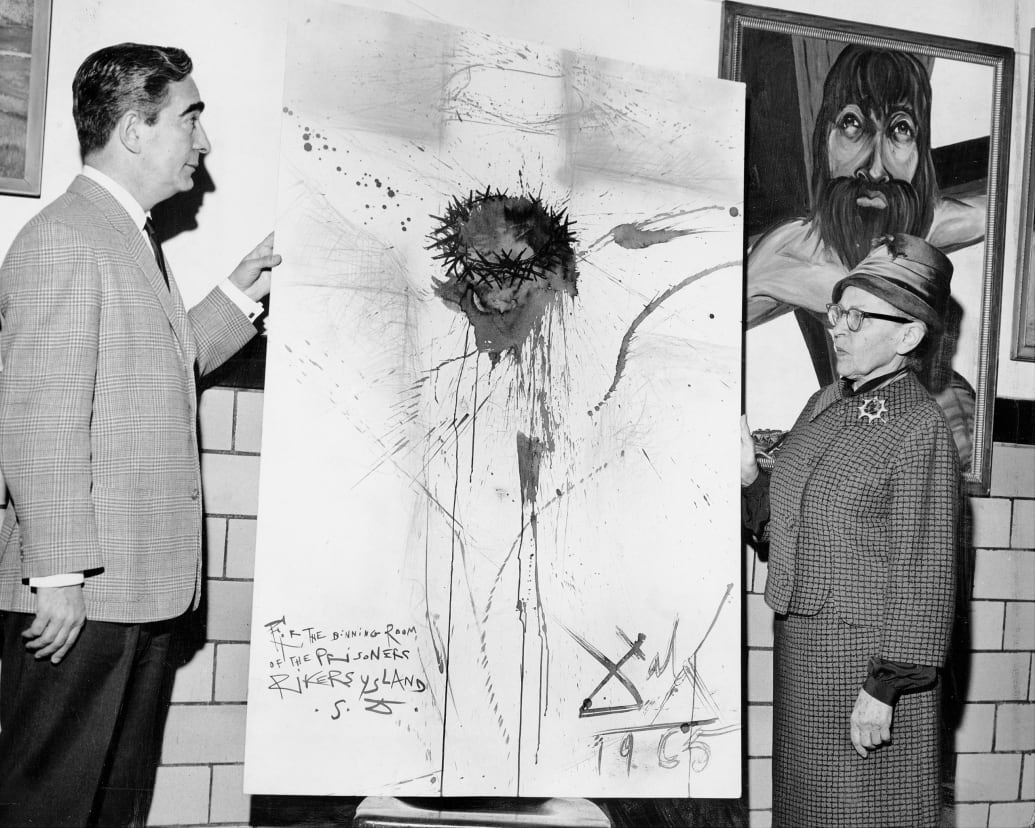

In only one hour and 15 minutes and battling a 101-degree fever, Dalí quickly painted a four-by-five-foot piece of paper with a surrealist crucifixion scene. He signed it with his name and a note (one that would have benefited from spellcheck): “For the inmates dinning room on Rikers Island. Dalí.”

Leonard Detrick/NY Daily News Archive via Getty

Then, Dalí’s business associate Nico Yperifanos hand delivered it to the prison with a few words from the maestro: “He'd like to give a message to the prisoners that you are artists. Don't think your life is finished for you. With art, you have to always feel free.”

The years passed, and one particular population at the prison—the one not gifted with the painting—began to feel a little too free with the resident art.

The painting originally hung in the cafeteria as instructed where it could be enjoyed by the prison’s main occupants. But over time, its origins were forgotten—by the administration, at least—and it began to take on some new color by way of red and brown splotches suspected to be ketchup and coffee stains. For 16 years, it hung on a wall overseeing the prison’s food fights until one forceful coffee cup grenade smacked into it in 1981 and shattered the glass that was not so sufficiently protecting it.

With that one cup of flying joe, the prison administrators finally took notice of the painting once more. By that point, as Robert Tanner put it in the Los Angeles Times, it was “a forgotten footnote in the art world,” and even the officials at the prison failed to remember that it was the work of a master. They sent it to be appraised and discovered that it was a genuine Dalí worth $250,000.

The painting was quickly removed from the cafeteria, and the prisoners for whom Dalí sketched Christ would never have access to it again.

The untitled Dalí was sent on a short tour of the U.S., then boxed up and safely stored in a prison office for several years. But eventually, the decision was made to put the painting on display once more. This time, it would grace the wall of a lobby used by prison employees, where it was secured in its original gold frame in a locked glass case in direct view of the guards as they came and went on their daily shifts.

Until March 2003, that is, when one of the guards who gazed at the piece every day hatched a plan to nick it.

On March 1, four guards arrived for the midnight shift at the building in question.

They had attempted to pull off the theft several nights earlier, but had called it off due to a heavy guard presence. But the cost was as clear as it was going to be on that March night, and the alleged ringleader pulled the fire alarm to clear the building, setting things in motion.

A second man dispatched two additional accomplices to different lookout areas before he swapped out the real Dalí with a fake.

Their plan was poor to begin with, but the execution left everything to be desired. While he never confessed, the group’s alleged ringleader, a man with the appropriately cinematic New York name of Benny Nuzzo, is believed to have created the copy that was put into the place of the missing painting.

It was noticeably smaller than the original, an instant tip-off, but the reproduction was also one that, based on descriptions, not even a child would have wanted to claim. Plus, the reproduction of the cafeteria stains were an entirely different color. It was bad.

Then, of course, there was the painting’s presentation. Yes, the glass case had been locked back up with the copy safely inside. But where the original had been displayed in its gold frame, the fake was simply stapled to the back of the box, sans frame.

The whole plan was amateurish at best, but when you factor in the location—a prison teeming with law enforcement officials who spent their days gazing at that exact painting (there were two guard booths in direct view of the Dalí)—it was stupidity at its finest.

The very next day, several guards reported that there was something wrong with the Dalí.

“'It looks like the painting has been replaced by a copy. That appears to be the case based on a consensus of nonexpert opinion, people who work near the painting and see it day in and day out,” Thomas Antenen, a spokesman for the Department of Corrections told the New York Times.

An investigation quickly concluded that the only people who had access to the work were the guards.

Andrew Savulich/NY Daily News Archive via Getty

With their pool of suspects narrowed down, the four suspects were soon uncovered and they quickly turned on each other. All four men were charged with second degree grand larceny, but in a strange turn of events, only the three followers were sentenced to jail time. The alleged ringleader of the whole operation, Nuzzo, was acquitted in a jury trial.

But before he got off scot free, he is believed to have made one critical decision that cost the art world and the prison dearly. The untitled Dalí has never been seen again, and one of Nuzzo’s accomplices claims that it never will be—he said their leader got nervous and destroyed the piece.

As the investigation came to a close, only one thing was certain. In this case, it was the prisoners who were robbed.