The Rich History of Black Roller Skating Rinks—and Their Civil Rights Legacy

Photo Illustration by Sarah Rogers/Photos Getty

As skates sell out during the coronavirus pandemic, black roller skaters urge fans to learn about how rinks played an important role in the civil rights movement.

United Skates, a 2019 documentary film highlighting the history of Black roller skating rinks, opens with a shot that is all-too-prescient for this summer of Black Lives Matter demonstrations: police sirens.

As Black families, many of them with children, wait to enter a roller skating rink, they are monitored by officers. Even at a recreational space long associated with nostalgia and good clean fun, the cops keep a close eye.

But then the doors to the rink open, and the audience is treated to a weekend night at the roller rink. Two men in matching neon camouflage pants skate in unison, one diving under the other’s legs without breaking rhythm in a feat of intoxicating athleticism.

Another man spins once, then twice, then three and four times, spotting his turns like a ballet dancer on wheels. People drop to the floor in unison. Though the space is strictly guarded outside, inside it is a place of unbridled, infectious joy.

“The idea of the film’s opening was to show as if you were backstage and then stepping out onto the floor,” Dyana Winkler, one of the film’s co-directors, said in an interview. “We wanted to show what the outside world feels like, and how it shifts and becomes this magical place once you open the doors. You see cops out there, and then that all falls away and disappears as you enter. It’s more colorful, more vivid, more clear.”

Along with telling the triumphant history of Black roller skating rinks, a narrative deeply entrenched in the civil rights movement, Winkler and her co-director Tina Brown shed light on a sad future. Across the country, rinks have disappeared. In one scene, a graphic of the United States shows dots where locations used to be in all 50 states. As time ticks from 1980 on, those dots vanish.

“It looks like a constellation, and you can see the stars going out,” Reggie “Premier” Brown, a 36-year-old Black roller skater from New York told The Daily Beast. Along with his wife Naadira and their children, Reggie’s attempts to keep rinks in business anchor much of United Skates.

Reggie has been skating since he was 12 years old. His mother and uncles were avid skaters and they spent every Thursday going to “Soul Nights” in Chicago rinks.

“One thing I remember most of all was seeing a whole bunch of people who looked like me,” Reggie said. “The legacy and history of roller skating as it pertains to the African-American community is not only massive as far as influence, but also in the success of roller skating—that’s been because of the consistent support of our community. Period. It’s been that way because we had to fight so hard to get it.”

In the documentary, elder skaters detail just what that struggle looked like. One man who experienced segregation in Chicago said that Black people were allowed one evening a week to head to the rink, called “Soul Night.” In Detroit, it was called “Hell night.”

Rinks were the site of many peaceful protests. One skater from Illinois named Reverend Koen speaks in the film about the KKK attacking picketers. The rink would later close. “They would rather die than integrate,” he says.

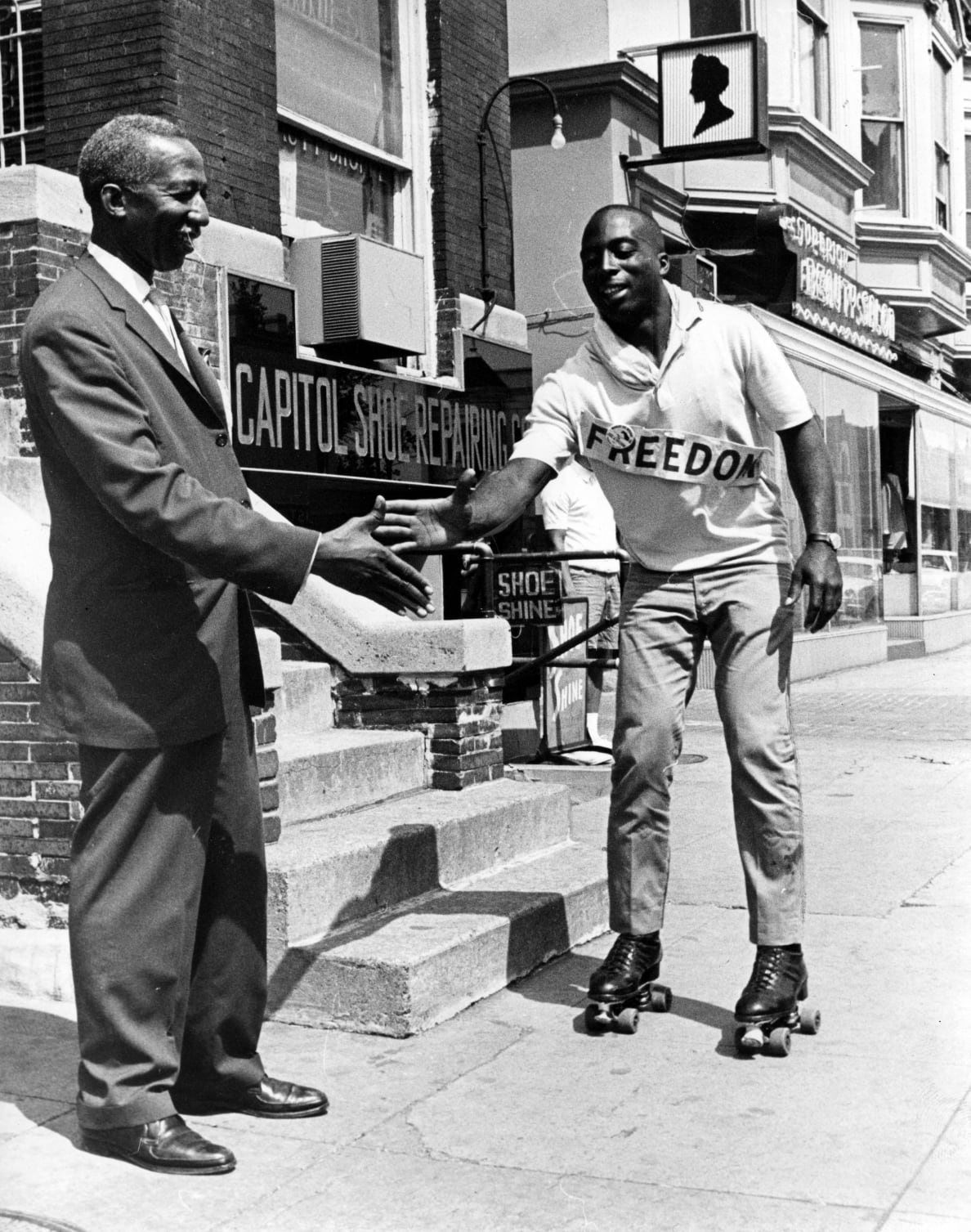

Ledger Smith, a semi-professional skater, is greeted by H. Carl Moultie, vice president of the D. C. branch of the NAACP, as he arrived by roller skates from Chicago to join the March on Washington, he is seen here in Washington, DC on August 27, 1963. Ledger left on August 17 and averaged between 70 and 80 miles a day.

Tom Kelley / The Washington Post via Getty

But determined Black skaters found a metaphor in their attempts to break down barriers at rinks: keep one foot in front of the other. “Forward forever and backwards never,” Reverend Koen says.

Ledger Smith, known as “Roller Man,” skated 685 miles from Chicago to D.C. to attend the March on Washington, wearing a placard that read “FREEDOM” around his neck. He lost 10 pounds on the way and almost got run over by a racist driver in Fort Wayne, Indiana.

“He didn’t do a single trick,” Reggie told The Daily Beast. “He was just persistent. Skating outside, those legs start to hurt. But he was rolling with purpose.”

As explicit segregation ended, racism at white-owned rinks became more subtle. “Black Nights” was no longer an acceptable term, so people came up with other coded ways to describe it. One part of the film tracks the different names rinks gave to these evenings: “MLK Night,” “Sepia Night,” “Soul Night,” and “Gospel Night.”

“What’s interesting is that audiences who are predominantly white get uncomfortable during that moment,” Winkler said. “You can hear gasps, or shock, or frustration. When you show the same scene to an audience of predominantly Black viewers, they laugh. They laugh because it’s so obvious. ‘Yup, that’s another one.’ For me, that was one of those eye-opening moments about how white America is so ignorant that we’re still surprised by police brutality.”

Reggie said he would not describe roller skating as an “escape.”

“This is my reality everyday, in the rink and outside of the rink, there is this constant fight for justice and equality,” he said. “On the floor, it’s me, the music, and the wood. That’s it. But even if the problems of my world temporarily cease to exist, at some point I’m going to unlace my skates and walk back at the door, and face the same adversities I did before heading in.”

The summer before he went to college in North Carolina, Reggie spent every weekend at a rink. On Fridays, the clientele skewed white. More Black skaters showed up on Saturdays. Reggie would be there both nights.

“I remember on Friday, I practiced and then left the floor to go to the bathroom,” he said. “It was a really nice, redone bathroom. The next night, I was on the floor and had to use the bathroom again. So I went to the same bathroom, but the door was locked.”

Reggie talked to the rink manager, who led Reggie down the hall to a different restroom. “I opened the door and it was the absolute worst, most disgusting site you’ve ever seen in a bathroom,” Reggie recalled. “There was stuff on the walls, no soap, no paper towels.”

He told the manager that just the night before he used the cleaner bathroom on the other end of the hall. Why wasn’t it opened on Saturdays?

“The manager said, ‘On Saturdays, people mess with the bathrooms so we close that one and use this instead,” Reggie explained. “That’s the moment you start to realize, oh this is the reality. This place is meant to be enjoyable, but they shut down one bathroom and open up another. I don’t think it gets more racial than that. There’s no excuse for something like that.”

Naadira Brown, Reggie’s wife, has also skated her entire life. They build a roller rink in the living room for their children, using wood from Home Depot as the flooring. “For us and roller skating, we don’t need a special time or a special reason, situation, or crisis to do it,” Naadira said. “We want to do it, and we love it.”

This spring, an ebullient TikTok went viral featuring an actress named Ana Coto rolling down a suburban Los Angeles street wearing bell bottoms and a megawatt smile. In interviews, Coto cited the Black history of roller skating as an inspiration. (As Digital Trends noted, she is of Puerto Rican and Cuban descent.)

Her popularity helped spur a mainstream interest in roller skates, with companies reporting a rise in sales. On Twitter, many bemoaned the lack of skates in stock, a sign that they had already been scooped up by wannabe roller girls and boys.

NBC News called skates a “hot new must-have” and Buzzfeed declared the activity “back in a big way.”

Black roller skaters like the Browns say the activity is for everyone as long as they learn the rich backstory of the pastime.

“Hey, we were skating all this time,” Naadira said. “This is not new. It’s not ‘reemerging.’ Even a simple Google search might have helped [news] writers be a little more factual. There is definitely much more recent history. Skating hasn’t been dead since the disco era.”

“My mom skates, I skate,” Reggie added. “All of my children skate. That’s multiple generations. When ‘trends’ like this happen, it indirectly takes credit away from the source that allowed for [roller skating] to survive.”

For her part, Ana Coto has spent time in the past two weeks protesting in support of Black Lives Matter and posting historical tidbits about Ledger Smith to her 65,000 followers. (Her Instagram bio reads, “Don’t hate, roller-skate.”)

"Roller skaters pack a rink on a Saturday night in Chicago."

Corbis via Getty

“Roller skating has opened my circle of friends, increased the size and diversity of it,” Coto said. “It’s given me so much richness, sure, but also opportunities to learn.”

Coto says “it’s clear” on her social media that (pre-pandemic) she visited roller rinks that are “both predominantly Black and predominantly white.”

“Roller skating is a parallel to life,” she added. “You’re not just immediately good at life, you have to try and fall and fail. And you also try to balance and communicate, engage with people who inspire you, engage with people who frustrated you. You find a way..”

Coto does not think she should be credited for any “resurgence” of roller skating in popular culture. “It wasn’t just me,” she said. “TikTok is a very powerful character in this story too. I just learned about this succulent that has these little flowers on the leaves. Just one little flower can sprout this huge new succulent in a matter of days. Some things do catch and spread like that.”

Coto believes there is “so much space” for new skaters. “I welcome them all,” she said. “Most of the community does. But of course I understand that people don’t want Black culture to be erased. It has been time and time again.”

“Roller skating is for everyone’s enjoyment,” Reggie said. “One of the biggest things you can do is learn the history. I’ve seen articles that have said roller skating was irrelevant since the ’70s. OK, so what have I been doing for the last 20 years? No, it hasn’t been irrelevant. Roller skating has continued to survive because of the African-American community and our ability to open up the culture to others who want to learn it.”