According to a Gallup poll taken last month, public confidence in the Supreme Court has hit an all-time low. Just 25 percent of respondents had “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in the court. That’s an 11-point drop from last year, and twice the drop in public confidence in other institutions.

Much of the court’s image problem comes the feeling that it has been politicized, be it the Republicans’ refusal to allow a vote on Obama nominee Merrick Garland in 2016, or the fact that one justice refuses to recuse himself from cases that may implicate in his wife in a effort to overthrow democracy (public confidence in the court among Democrats stands at just 13 percent).

It's also driven by the court’s recent decision to overturn the 50-year-old precedent in Roe v. Wade. The poll was taken before that decision, but after Justice Samuel Alito’s draft majority opinion was leaked to the press.

But this court has brought much of its legitimacy crisis upon itself. It has abdicated its most important and profound responsibility—safeguarding basic constitutional rights. And it has done so in a series of rulings that are overtly political, wildly inconsistent, and in some cases wrong on basic facts.

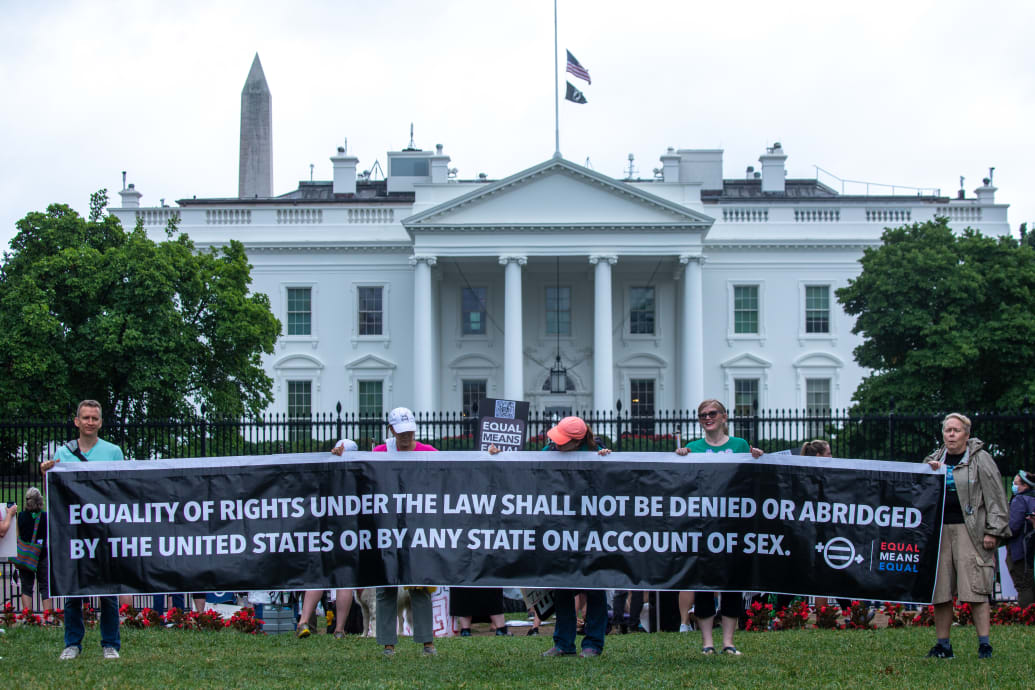

Abortion rights activists march to the White House to denounce the U.S. Supreme Court decision to end federal abortion rights protections.

Yasin Ozturk/Anadolu Agency via Getty

Beyond just overturning a half-century precedent guaranteeing the right to an abortion, during this term, the justices also gutted a 10-year precedent concerning the right to a competent attorney, a 50-year Establishment Clause precedent, and another 50-year precedent allowing people to sue federal law enforcement officers.

In Shinn v. Ramirez, the court ruled that federal courts are prohibited from considering newly-found evidence of a prisoner's innocence, even if the prisoner has proven his attorneys were incompetent in not discovering that evidence at trial or during appeals. Barry Jones, one of the death row prisoners in that case, is likely innocent. The court did not rule that it found Jones’ innocence claims unpersuasive. Instead, it ruled that to even consider the evidence of Jones’ innocence would undermine the state of Arizona’s sovereignty.

It ought to go without saying, but any justice system that willingly ignores evidence of a death row prisoner’s innocence is, fundamentally, illegitimate.

During oral arguments, several justices—including Chief Justice John Roberts, as well as justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh—acknowledged that to rule for Arizona would effectively overturn that precedent. They voted to do so anyway. Two justices—Roberts and Alito—even reversed their own votes from the precedent case, without explanation.

Justice Thomas’ majority opinion also included a critical factual error. Thomas claimed that Barry Jones’ lawyers conceded Jones would lose his state appeals if he isn't allowed to introduce the new evidence of his innocence. Even the state admits Jones never made that concession. But Thomas’ error will make it yet more difficult for Jones to get Arizona courts to rehear his case. Yet the court has refused to correct the error.

Finally, even as the majority ruled that Jones must pay the price for his attorneys’ mistakes, it gave Arizona prosecutors a pass on their own critical mistake. Prosecutors get leniency. Prisoners must be perfect. And if the court itself makes a mistake, well, the prisoner pays for that, too.

Unfortunately, these sorts of errors in enormously consequential opinions aren't uncommon. Perhaps the worst example is a 2002 opinion in which Justice Anthony Kennedy relied on a discredited pop science article about the recidivism rate of sex offenders. That ruling has since been cited by dozens of lower courts across the country to justify a variety of draconian policies, from residency restrictions to indefinite detention. The court has had several opportunities to correct the mistake. It hasn't.

The Supreme Court as of June 30, 2022

Fred Schilling, Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

The court has also relied on provably wrong assertions of fact in rulings on no-knock raids, drug dogs, police checkpoints, prosecutorial misconduct, roadside searches, and police brutality. None of these were ever corrected.

In the school prayer case this past term, the majority and the dissent couldn't even agree on one easily verifiable fact at the heart of the case—whether a football coach’s prayers were conducted in private and on his own time, or public spectacles that may have been coercive to his players. (The record pretty conclusively points to the latter. )

The court has also been inconsistent about how and when it applies legal doctrines, leading to the understandable impression that there is no set rule of law, just a series of theories from which the justices can pick to support their preferred outcome.

One example is the concept of federalism—how much of government should be handled at the federal level versus how much by the states. In Shinn, the majority deferred adjudication of a condemned man’s possible innocence to the state of Arizona, keeping in line with the court’s 30-year assault on the right to federal habeas corpus, or the ability of state prisoners to have their convictions reviewed by a federal court. (The court did gut a 10-year-old precedent, but in this instance the precedent—which created a very narrow path to federal court for some prisoners—was the anomaly.) In fact, the Supreme Court has consistently ruled that federal judges must defer to state court rulings on constitutional rights—even when state courts are wrong on matters of constitutional law.

Yet the Supreme Court has also been happy to interfere with state courts when it wants to preserve convictions, such as in 2015, when it reversed a Maryland appellate court’s decision to overturn a conviction won with dubious forensics.

This term’s case about suing federal police officers also illustrates this court’s tendency to cherry-pick whatever legal theory suits its interests. The majority all but overturned the 1971 case Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents. In that case, the court reasonably ruled that when federal law enforcement officers violate the Constitution, the victim should be able to sue those officers in court. The courts’ conservatives have never liked that ruling, arguing it was a judicially created remedy for rights violations that was never authorized by Congress.

But the entire point of the Bill of Rights is to explicitly enumerate those rights that are so important they can't be voted or legislated away.

Even here, the court has been selective about when it defers to political bodies. The doctrines of qualified and absolute immunity protect police and prosecutors, respectively, from lawsuits when they violate someone's constitutional rights. Like Bivens, these too are doctrines the court created from whole cloth, and with qualified immunity the court actually defied the will of Congress.

But those doctrines protect law enforcement, while Bivens allows them to be sued. Tellingly, the court has expanded the former, and now all but eradicated the latter.

Conservatives and institutionalists, including Justice Thomas himself, seemed aghast at the court’s diminishing stature, and have put the blame squarely on the court’s critics. But there's a parallel between the court’s current legitimacy crisis and how it has handled wrongful convictions. The court has long taken the position that the integrity of the justice system demands protecting the finality of convictions when there’s clear evidence the system got it wrong.

But turning a blind eye to wrongful convictions in the name of “finality” doesn’t confer real integrity, only the illusion of it. Similarly, this court’s defenders blame its plummeting authority not on its increasingly partisan decisions, contempt for precedent, and refusal to defend the Bill of Rights, but on the public’s failure to properly revere it.

That gets it precisely backwards. Authority doesn’t come from robes, or pomp, or neoclassical columns. In a democracy it is earned. And this court hasn’t earned it.