It has been 100 years since an out-of-work forester named Benton MacKaye came up with the idea for an Appalachian Trail connecting Maine to Georgia. Today we know the trail for the hiking opportunities it provides, but its inventor had something much more ambitious in mind. In the wake of his own personal tragedy, MacKaye imagined a mountain realm that would change the shape of American life.

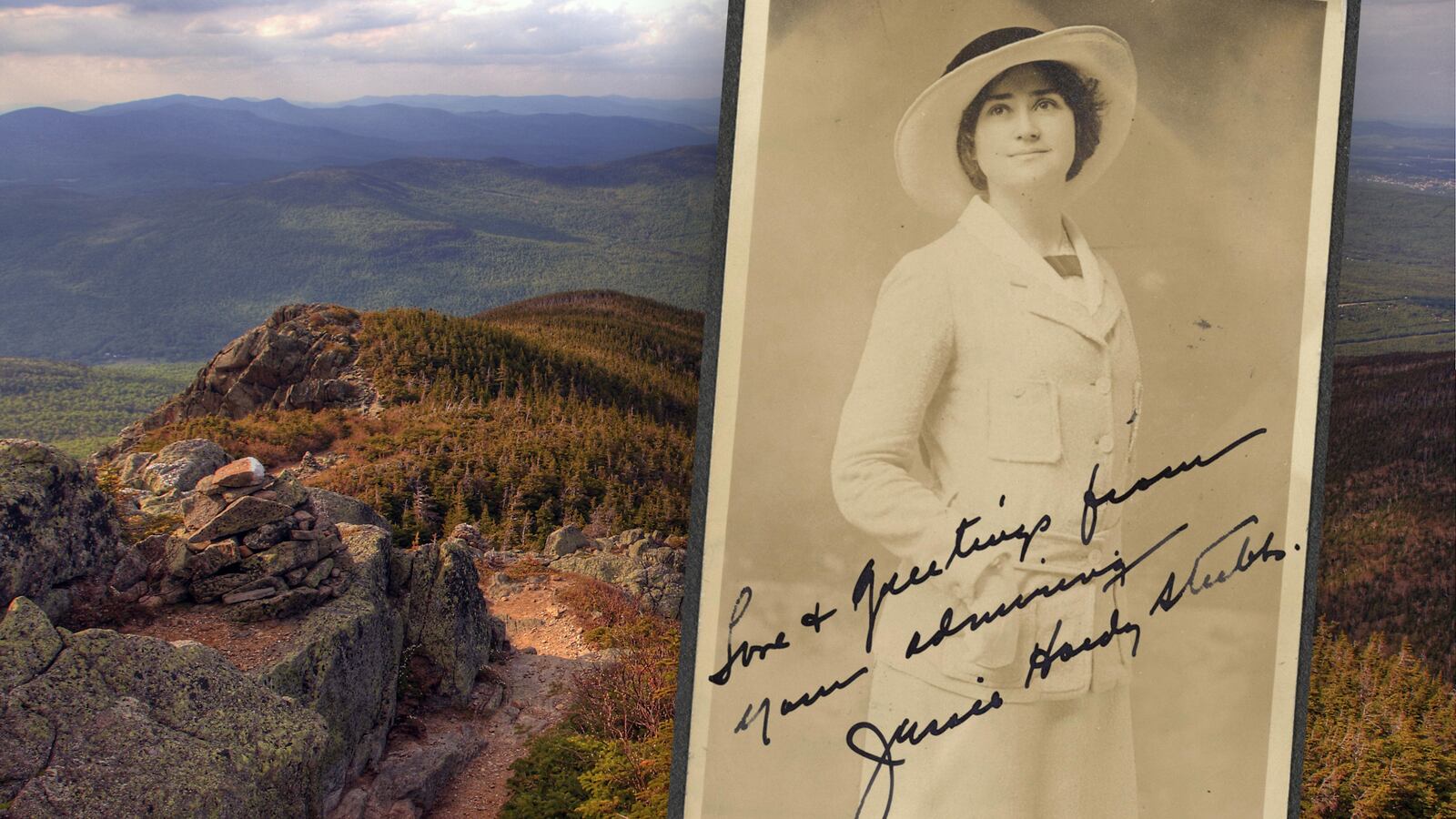

In 1915, MacKaye at the age of thirty-six married forty-year-old suffragist and social activist Jessie Hardy Stubbs, who went by the nickname Betty. She was far more prominent in her own field than MacKaye was in his, a leading organizer of efforts to grant women the right to vote. Betty MacKaye, like Benton, was devoted to social change on many fronts, and their marriage was as much a partnership in activism as it was a domestic arrangement. Washington, D.C. was their base, and they shared communal living arrangements with like-minded friends in a place the group dubbed “Hell House” for the hell-raising sensibilities of its residents. Both of them spent long stretches of time traveling and apart from one another, she to organize campaign activity, he to conduct his research.

In early 1918, Betty had a nervous breakdown, in the parlance of the time, racked with anxiety to the point that she could not function. Betty and Benton struggled to find something that would make her better, including a hospital stay in Washington. But the prospect of confinement made Betty more upset, not less, so they made arrangements to travel to the country home of a friend, in the Hudson River Valley north of New York City. It worked; in the calm atmosphere of the countryside, Betty regained her equilibrium, and the two resumed life together. They resolved to follow the same program if she were to have any similar episodes in the future.

The next year, MacKaye’s full-time employment with the federal government came to an end. He had written a major report outlining his proposal for planned settlement of forested land, “Employment and Natural Resources,” and had for the most part left behind the profession of forestry. MacKaye was growing more radical as his maturing profession moved in the opposite direction.

He drummed up some consulting work in Washington, then moved with Betty and a friend of theirs to Milwaukee, where the friend, Herbert Brougham, would edit a socialist newspaper and MacKaye would write its editorials. For a period of time, MacKaye’s mother and sister moved in as well. But just months after the MacKayes’ arrival in Milwaukee, a dispute erupted over Betty’s campaign for a women’s sex strike to stop global militarism. When the paper refused to publicize it, Brougham quit, and he and Betty attempted to use the dispute to drum up publicity for her campaign. Benton seems to have remained on the sidelines of the dispute. Nevertheless, the three activists’ joint undertaking was no longer viable, and they left Milwaukee for New York, where Benton looked for more work as a writer.

In the spring of 1921, MacKaye accepted the invitation of an old friend from Harvard to get away from the city and spend some time on Eastman’s farm in Quebec. MacKaye planned to help out his friend on the farm and spend time working on “a special piece of writing.” But a couple of weeks into his planned month-long stay in Quebec, MacKaye received a telegram urgently summoning him back to New York. Betty was in the throes of another breakdown—anxious, not sleeping, paranoid. Benton rushed back to the city and began to implement the plan they had agreed to three years earlier. Two days after his return, Benton and Betty and their friend Mabel Irwin went to Grand Central Station to catch the train to Irwin’s country home north of the city. Betty’s mood had improved with Benton’s return, but she had become anxious again as they left home, frightened that she would be confined against her will. Benton remembered the same pattern of behavior from the earlier episode, and was confident that Betty would calm down if they could just get her to the countryside. At the station, he stood in line for tickets while Betty and Mabel went to the restroom. But as the women were heading back to meet him, Betty seemingly took a wrong turn and began walking toward the building exit. Mabel reminded her which way to go; Betty ran. Benton, wondering why the two women hadn’t rejoined him, headed toward the restrooms and encountered a panicked Mabel, who told him what had happened. They notified the police and asked friends to join the search. Later that day, Betty’s body was found floating in the East River.

In the weeks that followed, after newspapers around the country reported the passing of the noted suffragist, and after a small impromptu memorial service in the wilds of Staten Island, Benton retreated to his older brother’s house in nearby Yonkers, and attended to the business of tying up his late wife’s affairs. He wrote letters to her many friends, relatives, and acquaintances, recounting the story of her death, and acknowledging their condolences. He wrote to Betty’s niece, “When we were married it seemed as if I could not love a woman more. But I found I could. I came to love her more and more as the years went by. We came to grow so near — in mind and soul — that her presence now seems at times even more vivid than when her body was here.” He seemed to take some consolation from the fact that Betty had escaped the demons that had been haunting her for years. A friend comforted him that Betty’s mental illness was bigger than anyone could manage, and the latest crisis was inevitable, “its threatened approach more or less clearly discernible to all who loved her.”

When, after several weeks, there were no more tangible tasks to be dealt with in the wake of Betty’s death, MacKaye accepted the invitation of his close friend Charles Whitaker to spend time at Whitaker’s country retreat on an old farm in the hills of western New Jersey. “You would adore the spot,” Whitaker wrote to the grieving MacKaye, “high in the mountains . . . and not a soul in sight.” Whitaker was editor of the prestigious Journal of the American Institute of Architects, and like MacKaye was deeply interested in reforming American life by designing and building an alternative. The two men had first become acquainted in Washington, running in the same circles of socialist reform, before Whitaker moved his office to New York. It was Whitaker, along with Betty’s traveling companion Mabel Irwin, who had positively identified Betty’s body.

At Whitaker’s farmhouse, MacKaye returned to the project he had been working on in Quebec. He drafted a “Memorandum on Regional Planning” that laid out his ideas on land, economy, and society, concepts he had been mulling over and refining for the previous several years. The memo provided examples of the kind of projects that a regional planner—that is, MacKaye—could undertake to demonstrate the value of this approach. At some point, perhaps at Whitaker’s urging, MacKaye set aside the larger concept and began to more fully develop one of these potential regional planning projects.

“Working out Appal. trail,” he wrote in his diary on June 29. As he drafted an article laying out his proposal, his host Whitaker got in touch with a friend, the New York architect Clarence Stein, whom Whitaker knew would see the potential in MacKaye’s work. Stein was the chair of the American Institute of Architects’ Committee on Community Planning, a group devoted to applying architecture’s expertise not just to individual buildings but to the entire urban fabric. Stein came out to the New Jersey farm; together the three men talked, hiked, and came up with a plan to launch the Appalachian Trail. Whitaker would publish MacKaye’s article in his magazine. Stein’s committee would provide an administrative home for the effort. And MacKaye would reach out to and organize the various stakeholders around his project.

“An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning” appeared in the October 1921 issue of the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. In it, MacKaye conjured a giant who strolled down the length of the Appalachian Mountains, viewing all of eastern America as a single landscape.

Resting now on the top of Mt. Mitchell, highest point east of the Rockies, he counts up on his big long fingers the opportunities which yet await development along the skyline he has passed. First he notes the opportunities for recreation. Throughout the Southern Appalachians, throughout the Northwoods, and even through the Alleghenies that wind their way among the smoky industrial towns of Pennsylvania, he recollects vast areas of secluded forests, pastoral lands, and water courses, which, with proper facilities and protection, could be made to serve as the breath of a real life for the toilers in the bee-hive cities along the Atlantic seaboard and elsewhere.

Second, he notes the possibilities for health and recuperation.

. . . Most sanitariums now established are perfectly useless to those afflicted with mental disease—the most terrible, usually, of any disease. Many of these sufferers could be cured. But not merely by “treatment.” They need comprehensive provision made for them. They need acres not medicine.

. . . Next after the opportunities for recreation and recuperation our giant counts off, as a third big resource, the opportunities in the Appalachian belt for employment on the land. This brings up a need that is becoming urgent—the redistribution of our population, which grows more and more top heavy.

To MacKaye’s giant, the Appalachian skyline provided a chance to craft a new alternative to the American way of life, grounded in the lessons that nature had to teach.

And this is the job that we propose: a project to develop the opportunities—for recreation, recuperation, and employment—in the region of the Appalachian skyline.

The project is one for a series of recreational communities through the Appalachian chain of mountains from New England to Georgia, these to be connected by a walking trail. Its purpose is to establish a base for a more extensive and systematic development of outdoor community life. It is a project in housing and community architecture.

The Appalachian Trail, in MacKaye’s conception, was the backbone of a new geography; like the railroads he had loved as a child, it would do more than just connect places, it would transform them.

Excerpted from THE APPALACHIAN TRAIL: A Biography by Philip D’Anieri. Copyright © 2021 by Philip D’Anieri. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Available now from HMH Books & Media.