By the late 1950s Minoru Yamasaki had established himself as a major figure in American architecture. The son of Japanese immigrants in Seattle, Yamasaki overcame endemic racism in both his country and his profession to rise to prominence with a humanistic approach to modern architecture, exemplified in projects including the Lambert Airfield in St. Louis and the McGregor Memorial Conference Center in Detroit.

In 1963, Yamasaki was featured on the cover of Time magazine after he won the commission to design the World Trade Center, but the job would come to mark a turning point in his career. Less than a year before the World Trade Center opened, one of Yamasaki’s first major projects, the massive Pruitt-Igoe Apartments in St. Louis, was slated for demolition in a media event considered by many to mark the end of the modernist experiment in American architecture. The critical rebuke of the World Trade Center and the spectacular demise of the Pruitt-Igoe apartments in St. Louis pushed him to the margins of the profession in the latter half of his life. Today, Yamasaki remains largely unknown despite his enormous influence on the history of American architecture.

Minoru Yamasaki cover of Time Magazine January 18, 1963

Justin BealThe following excerpt from Sandfuture describes the early stages of planning for the World Trade Center in New York, the process through which Yamasaki won the commission in 1962, and the critical reception of the project when it opened in 1973.

The island of Manhattan is built on three strata of course metamorphic bedrock—Manhattan schist, Inwood marble, and Fordham gneiss—that run north to south along the island’s cetacean spine. The bedrock abruptly dips several hundred feet below ground just south of Washington Square before rising again near Chambers Street. These geological contours account for the gap between the skyscrapers clustered in midtown and downtown, because tall buildings must be anchored on solid bedrock rather than on the glacial till that fills the valley between.

In 1955, David Rockefeller was Chase’s executive vice president of planning and development. A gradual exodus of white-collar workers from Wall Street office buildings to midtown landmarks like the Chrysler and Empire State buildings posed a problem for the Rockefeller family and the bank, which had significant real estate holdings in the financial district. On a February morning, real estate developer and family friend William Zeckendorf offered Rockefeller a ride downtown, during which he proposed a plan to bolster the value of the bank’s downtown properties with the construction of a spectacular new headquarters. Zeckendorf called his proposal—which involved an intricate sequence of sales, transfers, acquisitions, and demolitions within a tight tangle of downtown blocks—the “Wall Street Maneuver.”

To execute the maneuver, Rockefeller needed the support of another family friend, Robert Moses, who, in his capacity as the New York City Planning Commissioner, was the only man who could grant permission to permanently remove one block of Cedar Street, above which David would ultimately build One Manhattan Plaza, Gordon Bunshaft’s sleek International Style tower. Moses promised his support (in exchange for Chase’s support of his proposed Lower Manhattan Expressway) but warned Rockefeller that the long-term viability of downtown real estate would require a project of even larger proportions. In 1956, on Moses’ recommendation, Rockefeller founded the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association—a consortium of downtown executives—to devise a plan to stop the “slow economic strangulation” of Lower Manhattan. The association asked Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) to draw up a preliminary plan for a “World Trade and Financial Center” and hired the consulting firm McKinsey to do a feasibility study. When McKinsey concluded that the proposed project would almost certainly fail, Rockefeller ordered his aides to bury the report and pushed on, emboldened by his brother Nelson’s election as governor.

At a small press conference in January 1960, David Rockefeller formally announced a revised SOM plan for a massive “World Trade Center” near the Fulton Fish Market on the East River, and the Downtown-Lower Manhattan Association recommended that the Port Authority do a feasibility study. With an uncharacteristic flourish, Rockefeller coined the term “catalytic bigness” to define the project’s intended public purpose—to be deployed like an economic defibrillator with a shock of sufficient magnitude to alter the course of development in Lower Manhattan forever.

In the manuscript of a book that would be published the following year, Jane Jacobs dismissed the preliminary plans for the Trade Center as an act of “vandalism” against the authentic character—“the tumbled towers and jumbled jaggedness”—of Lower Manhattan. This is the only mention of the project in The Death and Life of Great American Cities, but there are inauspicious echoes of Rockefeller’s catalytic bigness in Jacobs’ admonition of the dangers of cataclysmic money, which pours “into an area in concentrated form, producing drastic changes,” but sends “relatively few trickles into localities not treated to cataclysm.” Cataclysmic money, Jacobs warned, behaves “not like irrigation systems, bringing life-giving streams to feed steady, continual growth,” but rather like “manifestations of malevolent climates beyond the control of man—affording either searing droughts or torrential, eroding floods.”

Like Moses’ Triborough Bridge Authority, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey was a quasi-governmental “public benefit corporation” that presided over nearly every piece of trade-related infrastructure that fell under its jurisdiction, which was poetically, if arbitrarily, defined by a circle drawn on a map with a twenty-five-mile radius around the Statue of Liberty. In addition to its influence and expertise, Rockefeller needed the Port Authority for two key reasons. First, the authority had access to far more capital than the city because it was able to issue its own revenue bonds, guaranteed with income from tolls and fees rather than from taxes. Second, it possessed, thanks to Title I of the Housing Act, the power to circumvent city building codes and public review processes and to seize property by eminent domain for any project that could be justified as serving a “public purpose.”

Aerial photograph of the future site of the World Trade Center. Found in 1963/64 Special Issue of “Via Port of New York”

HandoutThe Port Authority was run by Austin Tobin, a savvy former real estate lawyer with a reputation for ruthless, often autocratic efficiency, who had recently outmaneuvered Moses for control of New York City’s airports. Tobin lacked Moses’ charisma, but he was no less ambitious, and although he was initially suspicious of what appeared to be a speculative real estate venture, he needed a new high-profile project to put the authority’s extra capital to work before state legislatures could redirect it to mass transit as they had long hoped to do. If Tobin could justify it as trade-related, the Port Authority would build it.

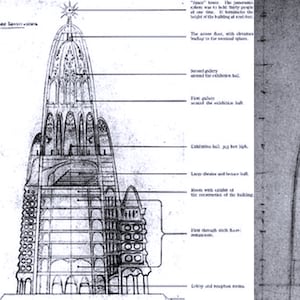

The authority partnered with a “genius committee” comprised of architects Edward Durell Stone, Gordon Bunshaft, and Wallace Harrison to produce a revised plan that was presented to the mayor and the governors of New York and New Jersey in the spring of 1961, the same year David Rockefeller became president of Chase. Nelson’s endorsement was a fait accompli (he had already begun stacking the Port Authority board with friends and political allies in Albany), but New Jersey Governor Robert Meyner rejected the proposal on the grounds that it had little to offer his constituents.

The project lay dormant for six months until the Port Authority secured the support of New Jersey’s newly elected governor Richard Hughes by agreeing to take over the failing Hudson & Manhattan Railroad and moving the project to the West Side to serve as a transit hub for New Jersey commuters. When the plan was approved in early 1962, Tobin created a World Trade Department within the Port Authority and named Guy Tozzoli, a brusque military engineer and construction expert who had worked for both Moses and Tobin, as its head. For reasons that are not entirely clear but suggest a desire to move away from architects known for their loyalty to the Rockefeller family, the Port Authority decided not to proceed with the genius committee, and the task of selecting an architect was entrusted to a newly formed search committee.

The candidates included I. M. Pei, Philip Johnson, Welton Becket, The Architects Collaborative/Walter Gropius, Carson, Lundin & Shaw, Kelly & Gruzen, Ely Kahn & Robert Jacobs, and Minoru Yamasaki. It is an odd list, a jumble of established masters and younger firms that suggests the conflicting desires of the various parties involved. It was also a list in which Mies van der Rohe was conspicuous by his absence. He was excluded because of his advanced age—the Port Authority feared that he would not live long enough to see the project through, and they were right.

Yamasaki was working on the Science Pavilion at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, less than two miles north of the tenement where he was born, when he received the letter formally inviting him to participate in the competition. In his autobiography, he remembers mocking the Port Authority for adding a seventh zero to the $280,000,000 projected budget before being informed over the phone that it was not a typo. He knew that the project was too big for his office and that undertaking it was a gamble, but, as he would tell Time magazine a year later, he recognized a “once-in-two-lifetimes” opportunity to prove himself on the world’s biggest stage.

Minoru Yamasaki (undated) John Peter Associates, photographer

Courtesy of Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State UniversityAs the proposal process moved forward, I. M. Pei withdrew for unknown reasons and Philip Johnson was dismissed for a lack of experience with large-scale projects. Gropius, by many accounts an early frontrunner, fell out of contention because his office appeared to be overcommitted. Among the remaining (and considerably lower-profile) firms, Tozzoli had a favorite. While he was working for Moses, Tozzoli had been sent to visit the Seattle World’s Fair, where he was singularly impressed by the way Yamasaki’s Science Pavilion conveyed a sense of “warmth and human scale so rarely found in modern architecture.”

While Yamasaki may have seemed an unlikely choice in a field of better-known architects, Tobin and Tozzoli were looking for something specific. They did not want a masterpiece, they wanted a pragmatic, popular building designed by an architect with whom they could work. Tobin and Tozzoli saw in Yamasaki an appetite for grand achievement balanced with accessible appeal and a reputation for working well with clients. In the context of the World Trade Center competition, the fact that Yamasaki was perceived as existing on the margins of the architectural establishment likely worked in his favor. While Yamasaki had been maligned by his peers for the populism of his recent work, it was precisely that ability to resonate with a public that positioned him perfectly to get the most import- ant commission of his career. As his former employer and genius committee member Wallace Harrison would later tell a reporter, Yamasaki “understood what people need in architecture.”

“Demapping” is a term used by urban planners to describe the removal of existing streets from an urban grid. Like the literal tabula rasa, demapping requires the physical erasure of the text of the city. Before the Port Authority could begin construction on the World Trade Center, sixteen densely populated acres of Lower Manhattan had to be cleared to accommodate the site. Thirteen city blocks would be removed from official municipal maps forever, and the only remaining underdeveloped quarter of downtown would be exploited to its full potential. An image printed in a Port Authority publication at the time shows an aerial photograph of Lower Manhattan with the site traced in a thick white outline. The collage seems to reduce the incalculable complexities of urban redevelopment to a simple application of scissor to paper (a gesture that would be ingeniously reversed by Ellsworth Kelly in his 2003 collage Ground Zero). The brutal clarity of the Port Authority graphic belies the aerial perspective of the urban planners—like Moses or Tobin or Bartholomew—who believed that a city must be approached as a network of infrastructure rather than an ecosystem of individuals. Twenty years earlier Moses had decimated the neighborhood of Little Syria when his Triborough Bridge Authority appropriated land to build the Manhattan approach to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel. At the heart of the land to be razed for the World Trade Center site, immediately north of where Little Syria had once stood, was Radio Row—a thriving commercial district of electronics stores overflowing onto Cortland Street.

When the Port Authority announced plans to clear space for the proposed “superblock,” the merchants and repairmen of Radio Row paraded a coffin through the streets declaring the death of the small businessman. Then they filed a lawsuit to stop the construction on the grounds that the project was outside of the Port Authority’s jurisdiction. Writing in support of Radio Row in the Nation, Desmond Smith called the proposed World Trade Center “Manhattan’s Tower of Babel” and accused the Port Authority of abusing its power and seizing land on behalf of a vast, for-profit real estate development under the guise of public benefit.

(cover) Battery Park Beach, May 15, 1977 Fred R Conrad, courtesy of The New York Times/Redux. Cover design by John Morgan Studio

Justin BealThere were, at least theoretically, some limits to what land the Port Authority could take by eminent domain. From the beginning, the authority’s involvement was contingent upon the project’s essential connection to ports and transportation infrastructure, but the specific language of the charter—which granted “full power and authority to purchase, construct, lease, and operate terminal, transportation, and other facilities of commerce”—left the limits of its jurisdiction ambiguous. The merchants of Radio Row were the first constituency to challenge Tobin’s claim that the World Trade Center served any essential “public purpose” at all, arguing instead that it was simply a speculative real estate venture. In April 1963, the New York State Court of Appeals dismissed a case filed by the Radio Row merchants and allowed the Port Authority to take all sixteen acres of the proposed site by eminent domain, judging that the project would positively impact the ports of New York and New Jersey by dedicating space to the “facilitation and development of world trade.” Ultimately, legislation would require that 75 percent of the World Trade Center tenants had to be either directly involved in international business or serving it, but what exactly that meant was unclear.

The World Trade Center officially opened on a rainy April morning in 1973, barely a year after the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe had begun. A faltering economy, falling tax revenue, labor strikes, and rampant crime had left New York in an unprecedented fiscal crisis, and early occupancy was low. As politicians sought to distance themselves from the project, neither Tobin, who was now retired, nor Mayor John Lindsay, who had so vehemently opposed the project, attended the dedication ceremony. When a reporter later asked Tobin why he was not in attendance that morning, he said only, “because it was raining.”

Awaiting the final reviews, Yamasaki had every reason to anticipate the support of Ada Louise Huxtable, whom he considered a friend and who had been an outspoken advocate of his work, but when it arrived, her review was a devastating rebuke. Huxtable had applauded the structural ingenuity of the initial proposal but later warned that the scale of the project might be received by the public “more as monster than marvel.” In her final assessment, titled “Big, But Not So Bold,” the buildings had failed. “These are big buildings, but they are not great architecture,” she wrote. “As a design, the World Trade Center is a conundrum. It is a contradiction in terms: the daintiest big buildings in the world.” The lobbies are “pure schmaltz,” the views “pure visual frustration.” Yamasaki’s team had tried for something special, but the result was nothing but “Disneyland fairytale blockbuster” and “General Motors Gothic”—her incisively branded adjectives carrying all the weight and force of an elite East Coast critic dismissing Yamasaki’s work as populist, provincial, and corporate.

Yamasaki wrote a meticulous seven-page rebuttal to Huxtable’s review composed in multiple drafts with the consultation of several colleagues, but his tone is defensive and his argument is as rambling as Huxtable’s was precise. Yamasaki attempts to reconcile his vision of what the project meant to him with the reality of how it was received, but the letter feels desperate and defensive. He quotes Emerson extensively—“beauty rests on necessities”—as if a stroke of elegant engineering was enough to justify the existence of the tallest buildings in the world. He returns continually to the efficiency of the design without addressing the existential question of what is accomplished by using no unnecessary material in the construction of a building that was largely unnecessary in the first place.

It is a heartbreaking exchange. The dissonance between Yamasaki’s intentions and his execution, between his vision of what the project could signify and the physical reality of what it had come to represent, reaches an uncomfortable climax in these seven pages. He closes the letter with a plaintive appeal to Huxtable that the success of the buildings will ultimately be determined by the people who use them. In her measured response, addressed affectionately to “Yama,” Huxtable explains, “I tried, in the brief space I had, to make it clear that you had a philosophical and structural rationale for your design; but I feel that the aesthetic effect is not really successful for buildings on this scale.” She continues: “As engineering, they are extremely impressive. I suppose that it is design approach, or interpretation of structure, that is the issue, and that, admittedly, can be a very subjective matter.” She signs off with a succinct, merciless valediction—“you are the architect and I am the critic and it is an honest parting of the ways.”

Excerpted from Sandfuture by Justin Beal. Copyright © 2021 by Justin Beal. With permission of the publisher, The MIT Press. All rights reserved.