Come one, come all, to the most titillating film of the year: Love, which maintains director Gaspar Noé’s reputation as France’s preeminent provocateur via a relationship saga marked by spraying, spurting explicit sex—in 3D!

Call it porn, call it filth, call it a juvenile exercise in literal and figurative cinematic masturbation—Noé is sure to welcome those barbs, as the director has made a career out of pushing boundaries by pushing his audience’s noses in the gooey and the gruesome. Only the former truly rears its head in Love, which opens with a man and a woman pleasuring each other, to completion, in one long, static, unbroken take. It’s an introduction whose graphicness makes immediately clear the NC-17-grade nature of this erotic endeavor. And in the process, it highlights the film’s intrinsic relationship to the rest of Noé’s in-your-face oeuvre.

Love focuses on American twentysomething Murphy (Karl Glusman), who lives an unhappy life in Paris with his girlfriend Omi (Klara Kristin) and their infant son. While rising from bed to care for the child, Murphy’s narrated inner thoughts reveal his misery over his present circumstances, and his longing for ex-girlfriend Electra (Aomi Muyock), whose unknown whereabouts have compelled her mother to leave Murphy an anxious voicemail. This, in turn, prompts a series of flashbacks to Murphy’s halcyon days with Electra, a tall, striking French brunette who first appears in Murphy’s mind as something like a specter—suddenly materializing before him in his apartment, where they once cohabitated—and then in extended recollections of their once-idyllic relationship.

Noé doesn’t structure his flashbacks chronologically, leaping backwards and forwards not only between Murphy’s present and past, but throughout his past as well. The result is something like a remembrance collage of ejaculations gone by, as Love details how Murphy and Electra’s desire to explore their sexual fantasies led to a threesome with Omi, as well as a subsequent, covert screw between Murphy and Omi that ended with a broken condom and an unwanted pregnancy. Even that, however, is only part of the film’s story, as it then proceeds to travel back even further to document the disintegration of Murphy and Electra’s amour—a slow process accompanied by sex scenes that segue from intimate, kissing-heavy romps (set to electric guitar solos or spare piano) to more aggressive, animalistic, unromantic doggy style get-togethers in public spaces (scored to thumping electronica).

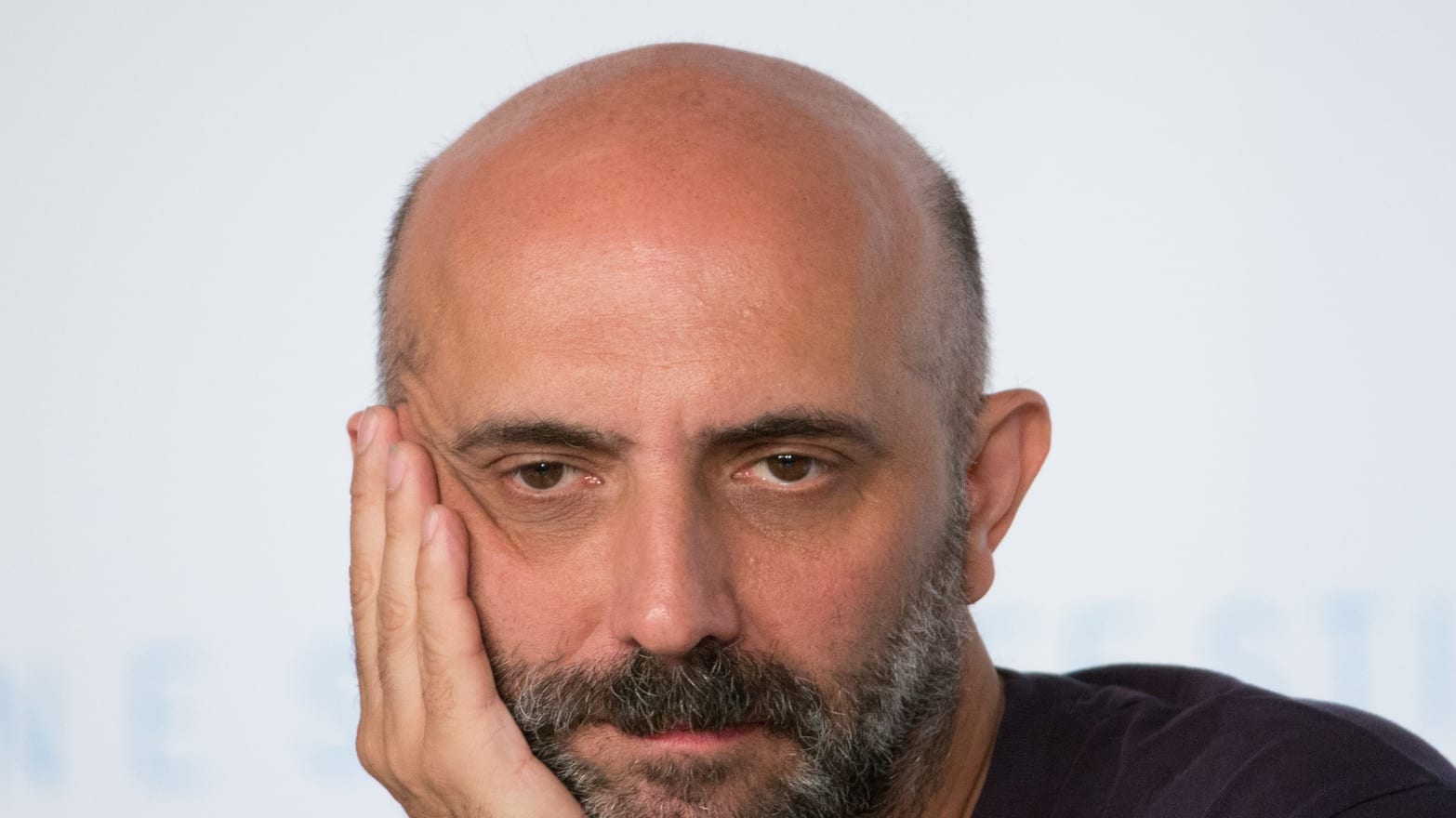

Did I mention that Noé includes a close-up of a penis climaxing directly at the screen in 3D? And a trip to a red-drenched sex club (shades of his prior Irréversible) where unbridled orgies are the norm? And also, a view of sex from inside Electra’s vagina? Such is Love, a film whose desire to shock and arouse comes from a place both sincere and sensationalistic—as well as autobiographical. That last element becomes obvious when Murphy states his desire to name his son “Gaspar,” and again later when Electra reveals that her ex is named “Noé”—and is played by the director himself, in a funny wig covering his bald head, as a married older man intent on using his money and influence to continue screwing Electra. Self-mockery, self-incrimination, and self-gratification all converge in Love, which reflects its maker’s interest in scandalizing and horrifying through blunt-force tactics, including via dialogue that’s never less than hammer-over-the-head unsubtle.

As such, it’s a natural extension of the work Noé has been doing since he burst onto the scene in 1998 with I Stand Alone, a riveting, no-holds-barred character study of a middle-aged butcher (Philippe Nahon) whose terrifying rage drives him to commit all sorts of atrocities, including, most famously, killing his unborn child by kicking his callous, pregnant mistress in the belly. A blistering reflection of contemporary French resentments and rage, it’s a film that derives its intensity from its bludgeoning nastiness, even as it operates with a mischievous prankster’s glint in its eye—as evidenced by its infamous gimmick, borrowed from genre legend William Castle: a conclusion-prefacing title card that cautions viewers, “You Have 30 Seconds to Leave the Theater.”

If I Stand Alone was Noé’s warning shot, 2002’s Irréversible was his full-on assault.

Perhaps the most singularly unpleasant viewing experience of the 21st century, it recounts the tragedy of a couple (Monica Bellucci and Vincent Cassel) destroyed by rape and the subsequent, violent response to it. Noé’s sophomore feature is dramatized with unflinching directness, his camera—as in the notorious 8-minute assault scene—endlessly lingering on brutality and violation. It’s also a color-coded tale rife with references to his preoccupations (anal sex, jealousy, 2001: A Space Odyssey) that’s told in reverse à la Memento, the better to evoke his favorite theme, which is both spoken and presented in on-screen text: “Time Destroys Everything.” That idea is also tackled by his 2009 follow-up, the hallucinogenic fantasia Enter the Void, which assumes the POV of a dead drug-dealing kid’s ghostly spirit as he floats in and around neon Tokyo, following around his sister and delving into his past—including the most horrifying movie car crash in recent memory—while also taking time to gaze at some graphic sex between people with glowing crotches.

For all of their attempts to incite outrage, Noé’s first three films are concerned with the progression of time, the fleeting nature of pleasure, and the inescapable longing to recapture a joyous past. That yearning for an impossible bygone moment is again evoked by Love, which—in a manner similar to the running-backwards Irréversible—uses circular imagery and vacillates between time periods in order to suggest how its Salò and Kubrick-loving wannabe-filmmaker protagonist (an overt proxy for Noé himself, to the point that he even has Enter the Void’s “Love Hotel” in his bedroom) is consumed by his craving for the pulsating “sentimental love” he briefly shared with Electra. Like the rest of Noé’s output, it’s a story that marries juvenile luridness and pestering button-pushing with an authentic sadness over impermanence, and a desperate need to fight against it.

It’s hard to view Love as scintillating drama, what with its one-note characters articulating little more than platitudes—or, in Murphy’s case, Noé’s own unsubtle feelings about movies, sex and love. And as a form of extreme cinema, it remains at once graphic and still far less gnarly and gonzo as your average PornHub clip. However, as an example of its writer/director’s obsession with rewinding time—back to more blissful early romantic days, if not all the way back to the womb (note its, and Enter the Void’s, views from inside a woman’s birth canal)—Love employs carnal centerpieces for candid self-expression. It’s another step in Noé’s continuing cinematic reversion therapy.