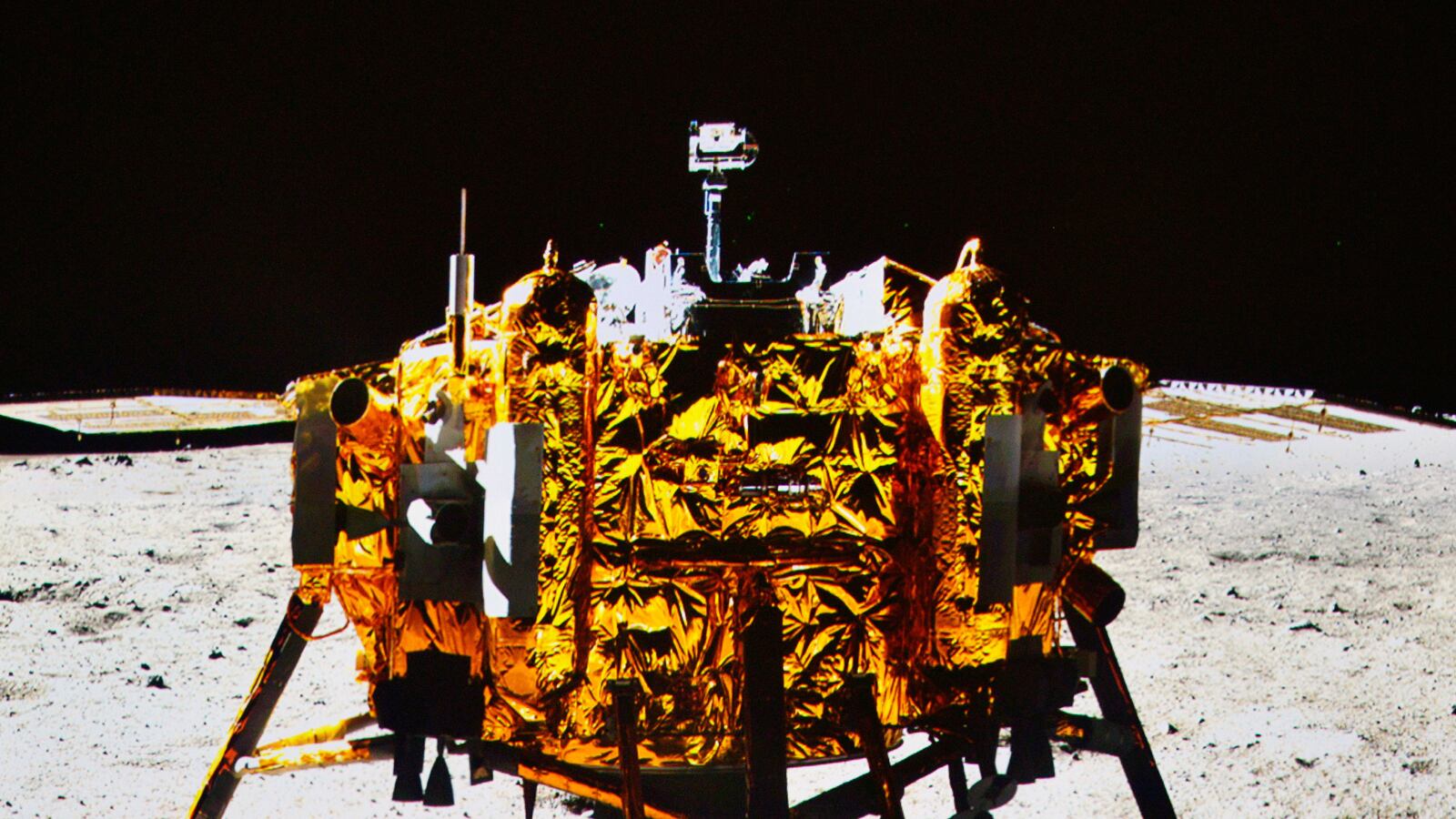

Thanks to China joining the elite club of countries that have carried out successful moon landings, 2013 will definitely be remembered as a special year in the annals of Chinese science. What’s likely less widely appreciated in some quarters is that it’s also been a banner year for Chinese science fiction.

This genre has had its share of dramatic ups and downs in the past, with the Communist Party literary establishment treating it as a suspect form for much of the last half-century. Now, though, it is definitely on a roll. Science fiction novels are selling briskly in China. Foreign specialists in Chinese literature, only a few of whom paid attention to the genre twenty years ago, now routinely take it seriously as a subject for scholarly attention. And Chinese SF has become so mainstream that the official Xinhua News Agency even found a way to bring practitioners of the genre, such as bestselling author Liu Cixin, whom they described as “one of the China’s most celebrated sci-fi writers,” into their campaign to use the lunar breakthrough to buttress national pride. The December 17 Xinhua article “Chinese sci-fi writers laud moon landing,” not only quotes Liu and other SF authors on the accomplishments of the country’s space program but also reminds readers that Lu Xun, the country’s most venerated modern literary figure, began his career by translating works by Jules Verne and wrote in 1903 that science fiction could play a crucial role in “the advancement of the Chinese nation.”

Lu Xun’s famous comment appeared in the introduction to the translation he did (working from an earlier Japanese edition) of Verne’s A Journey from the Earth to the Moon, a work that presciently predicted that Americans would someday take the lead in lunar expeditions. The young intellectual’s interest in foreign SF had been sparked by commentaries on the genre by the country’s most famous progressive intellectual of the day, Liang Qichao. Liang celebrated science fiction’s ability to introduce readers to new technologies and new ways of thinking simultaneously, and in 1902 even tried his hand at a story with some SF dimensions. Titled “The Future of New China,” the tale was set in a Shanghai in the far-off year of 1962 that was hosting the first-ever Chinese World’s Fair.

Some but not all specialists consider Liang’s “Future of New China,” which seemed especially topical a few years ago when the 2010 Expo, the country’s first World’s Fair, was held in Shanghai, the first Chinese work of science fiction. The other competitor for this title, which has more of the elements we associate with the genre, is a slightly later story, “Tales of the Moon Colony,” which obviously has closer links to current headlines. Given its greater topicality and the way it fits in with discussion of Lu Xun’s translation of Verne, it’s hardly surprising that the December 17 Xinhua article flags “Moon Colony,” rather than Liang’s “Future of New China,” as “the nation’s first modern science fiction work.” It also describes it as a story that “marked the beginning of generations of Chinese sci-fi writers’ lingering attachment to the moon.”

Lu Xun and Liang Qichao were not the only famous Chinese intellectuals to engage with the genre during the first half of the last century, nor was the moon the only orb that fascinated Chinese writers who soared into space in their imaginations. A novel that underscores both these point is Cat Country. Written in the early 1930s, it’s by Lao She, who is best known in the West as the author of realistic novels, such as Rickshaw Boy, and was once thought to have a good shot at becoming China’s first winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Lao She’s sole foray into the fantastical, its action unfolds on a Mars populated by feline-like humanoids and its narrator is a Chinese astronaut. His craft crashes into the planet, killing the other member of his crew, and, after a series of adventurers with the Martian Cat People, he is ferried back to earth by—in a nod to Verne, perhaps—a French rocket.

As this brief sketch suggests—and works by pioneering scholars of Chinese SF such as Harvard’s David Der-wei Wang and Heidelberg’s Rudolf Wagner confirm—the genre’s first golden age in China began early in the last century, which makes it nicely symmetrical that it’s second one started around the beginning of this one. Here are some noteworthy recent milestones, relating both to appreciation and translation of old works and production, dissemination and analysis of new ones:

In 2012, Renditions, the world’s leading periodical devoted to translations from Chinese into English, brought out a fascinating special double-issue that divided its attention between early sci-fi from the final years of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) and contemporary stories in the genre.

This spring, Pathlight, a Beijing-based periodical specializing in literary translation, devoted most of an issue to new works of Chinese SF.

Over the summer, Tor Books announced that it would be bringing out an English language edition of Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Trilogy, a wildly popular series that has sold over 400,000 copies in Chinese.

Early this fall, Penguin reissued Cat Country, making use of a 1970 translation by William Lyell and including as well an excellent new introduction by Ian Johnson.

2013 was also the year that Science Fiction Studies, the leading American scholarly journal in the field, issued its first special issue on China; it includes articles by academics based in different parts of the world as well pieces by Liu Cixin and two other contemporary Chinese science fiction writers, Han Song and Yan Wu.

Xinhua’s “Chinese sci-fi writers laud moon landing” illustrates one natural way that current news out of China and the historical roots and contemporary flourishing of the country’s SF tradition can be brought together. It’s worth noting, though, that this upbeat approach is not the only option here. Chinese science fiction, like that of other countries, has its dystopian side, and so, lately, have some news stories relating to China.

It would be interesting—though not something that Xinhua would ever go in for—to see how Chinese science fiction might help us place not just the lunar landing but other 2013 news stories into perspective. The year began with reports of thousands of dead pigs floating down rivers near Shanghai, and images of a Beijing cityscape that was dotted with futuristic buildings that were hard to make out clearly due to an otherworldly-seeming blanketing of toxic smog. These call to mind the dark imaginings of science fiction dystopian writers concerned with the environmental costs of development. Recent reports of Chinese government efforts to sweep websites clean of information it dislikes, of arrests of crusading lawyers and civil society activists, and of ordinary citizens being beaten by thuggish law enforcement agents, meanwhile, fit in with SF writings in the Orwellian vein. And one finds both sorts of dystopian authors represented in the annals of Chinese sci-fi.

Where might a darker themed counterpart to Xinhua’s celebratory story begin? One logical old place to start would be with Lao She’s Cat Country. It evokes a Mars whose inhabitants behave brutally toward one another and boast of the grandeur of their civilization while letting their cities decay.

A more recent departure point would be The Fat Years by Chan Koonchung, a writer who began his career in Hong Kong and later moved to Beijing. The Fat Years, which is often described as a Chinese counterpart to 1984 but also contains Brave New World-like elements and a shout out to Aldous Huxley, came out in 2009 in Taiwan and Hong Kong and then in an English language edition two years later. Banned for sale on the mainland, where the author continues to live, it is set in a China of the near future (well, of today, as the setting is 2013), where the water supply has been laced with a bliss-inducing drug that keeps most people from questioning the authority of an all-powerful Party. One key plot element is that the authorities have managed to make nearly everyone forget and squelched discussion of traumatic events of the recent past.

Chan was not among the Chinese authors whose opinion on the lunar landing Xinhua reporters sought. And if the 25th anniversary of the 1989 massacre that put an end to the Tiananmen Square protests comes and goes without public commemoration in Beijing next June, as seems very likely, we should not expect them ask him, or any other Chinese author, how that curious fact fits in with their works of speculative fiction.