The afternoon Jessica Zucker had her miscarriage, she was 16 weeks pregnant and home alone. She hadn’t been in labor long when, in her upstairs bathroom, the baby slid out of her. Bleeding and screaming in horror, Zucker called her doctor. Then she cut the umbilical cord.

Pregnancy loss is shockingly common, but we rarely talk about it. In the United States, roughly 10 to 20 percent of all pregnancies end in miscarriage, defined as the loss of a fetus before the 20th week. (A stillbirth is a pregnancy loss after the 20th week.) We struggle to talk about miscarriages because they are traumatic and overwhelmingly sad. They are painful and confusing. And despite being something we have no control over, miscarriages are often shrouded in a kind of cultural shame.

Zucker, a clinical psychologist who specializes in women’s reproductive and maternal mental health, was familiar with the deep feelings of guilt, shame, and isolation that linger after the physical pain of a miscarriage has passed. In her clinical practice in Los Angeles, she regularly treats women who have suffered miscarriages and stillbirths. Increasingly, Zucker noticed, her patients were also suffering another affliction: the inability to talk about their pregnancy losses with family, friends, and coworkers.

This August, Mark Zuckerberg announced on Facebook that he and his wife are expecting a baby girl—and that they’ve had three miscarriages. In a heartbreaking essay that’s become perhaps the best-known contemporary narrative on the topic, New Yorker staff writer Ariel Levy vividly recounts having a miscarriage in the bathroom of a hotel room in Mongolia. These kinds of stories capture the public’s attention and help chip away at the stigma surrounding miscarriages. But they don’t change the fact that in our culture, pregnancy loss remains a taboo subject.

After her miscarriage, Zucker experienced firsthand how well-meaning sentiments can backfire, sometimes ruining people who are already in a state of ruin. “At least you look good,” one woman told Zucker. “At least you know you can get pregnant,” a friend said.

In both her personal and professional lives, Zucker became painfully aware of how, as a society, we sorely lack authentic ways with which to talk about miscarriages. So she decided to do something about it.

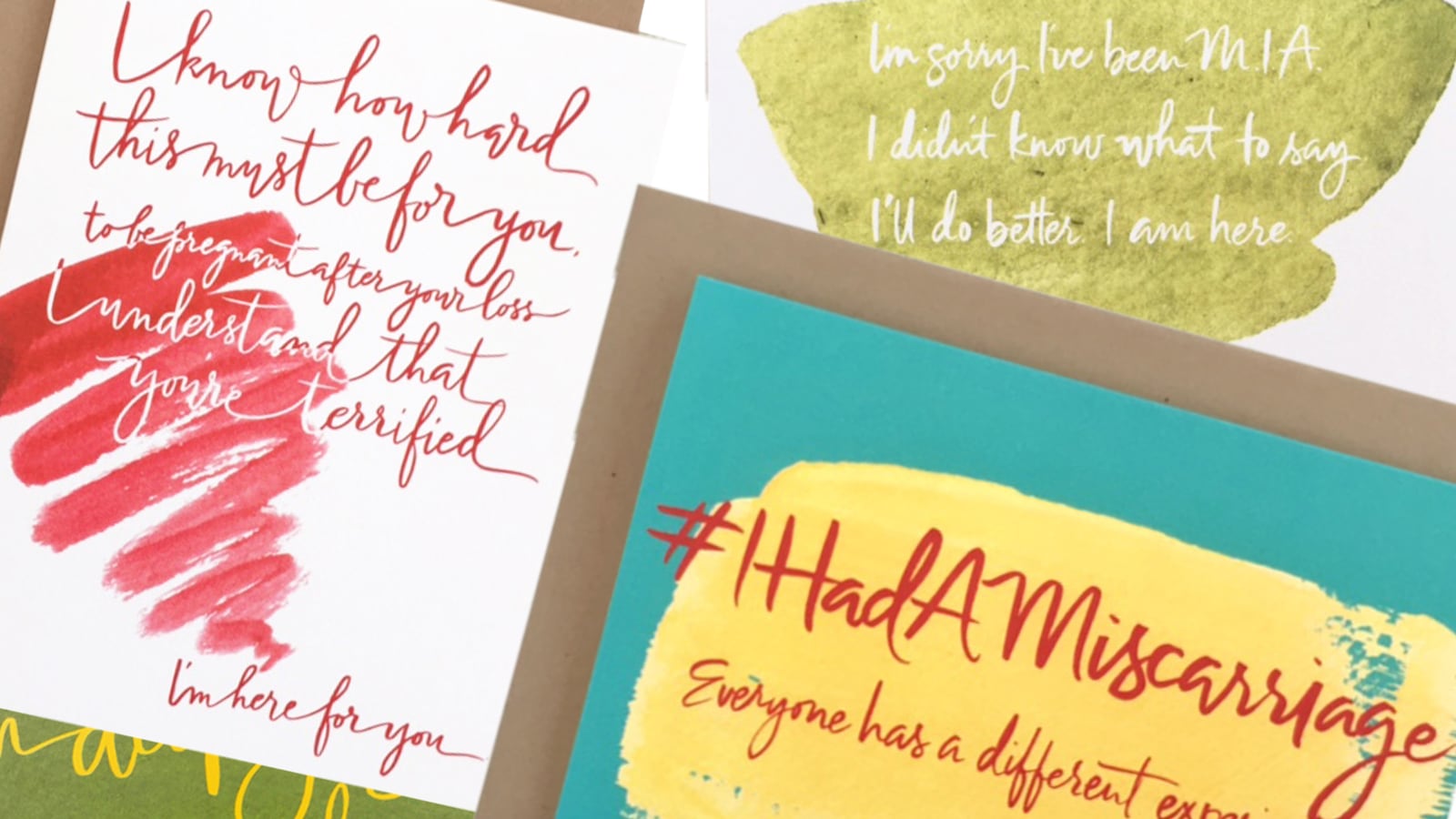

Today, in anticipation of Pregnancy and Infant Loss Remembrance Day on October 15, Zucker is launching a line of empathy cards focused on pregnancy loss. With vibrant colors and crisp calligraphy, the cards express in raw, real terms what a woman who has had a miscarriage or stillbirth desperately wants—and needs—to hear.

Greeting card aisles, with all their platitudes and hackneyed sentiments, don’t offer much in the way of genuine sympathy. Most of us settle for the least corny “Get Well Soon” card we can find and hope the recipient understands we tried our best. Zucker’s emotionally direct cards, in contrast, say exactly what we mean to say. With them, Zucker hopes to help people talk about miscarriages and shift the cultural conversation surrounding pregnancy loss.

When Aliza Kaplan, a law professor in Portland, Oregon, began trying to get pregnant in her late thirties, she had two miscarriages in a span of six months. Her doctors told her to keep trying. “Eventually, one will stick,” said one highly recommended OB/GYN. “See you next time,” her midwife joked. No one in the medical community spoke to Kaplan about loss; no one discussed the physical and emotional pain.

“I was lying there with a baby that didn’t have a heartbeat, and not one doctor said, ‘I’m so sorry,’” Kaplan told me. She and her husband were shocked by the lack of empathy. Before long, they stopped trying to get pregnant. These days, her students are sometimes shocked when she casually mentions her miscarriages. For Kaplan, miscarriages are one of many sad things in life that are uncomfortable to talk about—but, she stresses, women need to feel allowed to talk about them.

The cards are handmade by Anne Robin, a Los Angeles-based calligrapher who’s been in the business for over 15 years. For Robin, like Zucker, the cards are a deeply personal project. The mother of two boys, Robin has been pregnant seven times. After each of her five pregnancy losses, she struggled to talk about them with her close friends, who, despite meaning well, often said the wrong thing.

“One acquaintance said, ‘The baby must not have been viable, so it’s better this way,’” Robin told me. “Mostly, though, people just went silent.”

Last October, on Pregnancy and Infant Loss Remembrance Day, Robin shared the story of her losses on social media. The reactions were overwhelming. “I felt so much better—like my secret had been let out,” she said. “It felt good to be validated.”

When women share their stories of pregnancy loss with other women, the response is often, “I’ve had one, too.” Robin was shocked to learn that several of her friends had also miscarried. “But people don’t talk about it, so you feel very alone,” she said.

For both Zucker and Robin, the cards express what they wish people had said to them after their lost pregnancies. “The cards don’t beat around the bush,” Robin said. “They’re blunt and honest. My hope is that they give the person who receives them a little piece of comfort. Not pretty or sentimental comfort—real comfort.”

When we don’t know what to say or how to act, we often say the wrong thing or say nothing at all. This is a natural response. But pregnancy is also natural, and when it goes wrong, like it does for so many women—when what Ariel Levy calls the “blood and birth and tragedy of a distinctly female nature” is suddenly right in front of us—we cannot stay silent. We need to be able to grieve lost pregnancies together. We need to find ways to honor loss.

The more we talk about miscarriages, the less stigmatized they become. Jessica Zucker’s empathy cards, by filling a particular void, start the conversation; it’s up to us to keep it going.