Thirty years after the Jonestown massacre, Sandra McElwaine remembers her unlikely friendship with its most famous victim—Congressman Leo Ryan, who was gunned down on the tarmac.

Meeting Leo Ryan was like encountering a whirlwind, an exuberant force of nature. He put out his hand, smiled and sort of swooped into my life at a dinner at the Saudi Arabian Embassy in the spring of 1978.

He told me he was a congressman from San Francisco. I told him I was a reporter for the Washington Star and the conversation took off. By the end of the evening he had asked for my number and asked me out. He was attractive and fun and not a political stiff, so I accepted and a few nights later he arrived to pick me up.

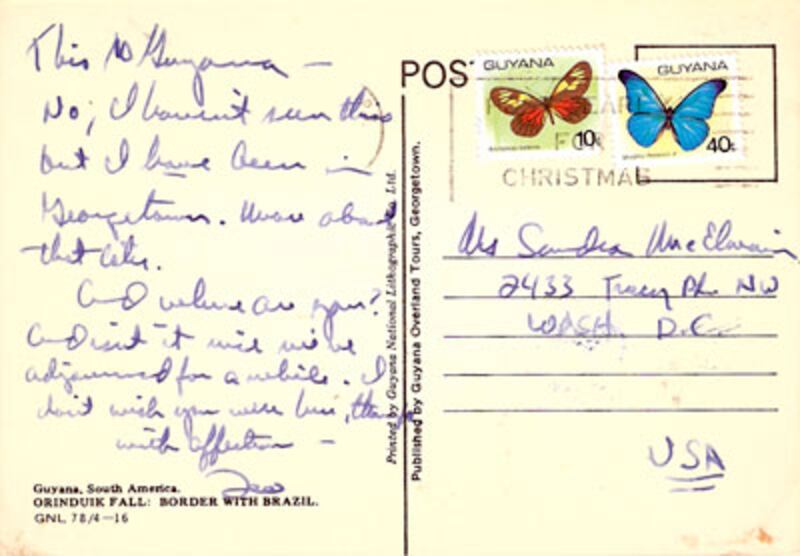

I found a post card on the floor mixed in with the pile of mail. As I turned it over I saw Leo’s signature. He must have sent it shortly before he was killed. I think I screamed.

In between those two events, however, there was a certain amount of consternation. I was recently separated and this was my first real date in years, so a couple of friends became deeply involved. One, a senate spouse, checked all available official documents on his background and pronounced him, “very interesting.” Another worked the grapevine and deemed him to be a “safe” date . But after I got to know him the latter was not an adjective I would ever have applied to Leo Ryan. Concerned and kind, he was also the ultimate risk taker, an iconoclast with an edgy, hard charging quality about him.

That night we went to the movies and saw Brooke Shields in “Pretty Baby”, strolled the streets of Georgetown and went back to his Capitol Hill house and talked. He told me about growing up in a family of strong-willed women, supporting the release of Patty Hearst, and going undercover in Folsom prison where he was locked up for ten days in order to discover what conditions really were. (On a side table in his office kept a chess set made from toilet paper and tooth paste, a gift from the inmates on Death Row.) I got home at 1:30 AM and there were umpteen frantic messages from my friends. Where was I???

Leo and I became friends. When he was in town that summer he would pop by, a craggy blue-jeaned figure, usually with a six-pack. He would sit in my garden, often reviewing the world situation with my teenage son, who genuinely liked him because Leo always treated him as an adult.

The last time I saw Leo was mid-November. We had dinner at his house—he was a pretty good cook when he had the time—and he told me about an upcoming trip to Jonestown, Guyana. There was a foreboding in his voice. He was going, he explained, because so many of his constituents had expressed grave fear about relatives and friends who had followed their spiritual leader, the messianic Reverend Jim Jones of Peoples Temple in San Francisco, to a remote commune in the jungle of the former British colony. He was frustrated that the State Department had stonewalled his attempts to find out what was going on in Jonestown.

He’d telegrammed Jones that he intended to visit the settlement.

As we said goodnight, Leo said he would call when got back and would probably spend Christmas in Washington. He planned to go under-cover again. This time as a postal employee, a mole in the main Post Office to check complaints of poor working conditions.

He left for Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, with several members of the media and a small contingent of concerned family members in tow. (His former aide, Jackie Speier, who accompanied Leo and now holds his congressional seat, was so apprehensive about this trip that when she put a bid in on her first home, a condo in Arlington Virginia, she made the deal contingent on her safe return from Jonestown. She also insisted Leo write a will and placed it in a top drawer of her desk.)

The next I knew it was November 19 and I heard about the horrific shootings at the small airport in Guyana: Leo’s murder and the suicide-murders of more than 900 in remote Jonestown.

Since then, I’ve learned what happened. After meeting with embassy officials in Georgetown, Leo and his group made their way to the compound in Jonestown where they were eventually allowed to visit with members, despite resistance from Jones. He interviewed a number of people, had dinner, and spent the night. During the visit, roughly 40 members quietly told Leo and his entourage they wanted to leave.

The next day Leo lead a group of 15 defectors to a local jungle airport. Jones, who held his followers captive on the pain of the death, sent a tractor trailer with several of his lieutenants brandishing weapons at the end of the runway and mowed down Leo and a couple of journalists, wounding many others.

Later that day, Jones sent a coded message to the members of his Peoples Temple church saying that some of the Jonestown residents had betrayed them, and asking his followers to take their own lives over facing the authorities because of what Jones had done. He demanded parents kill their children first.

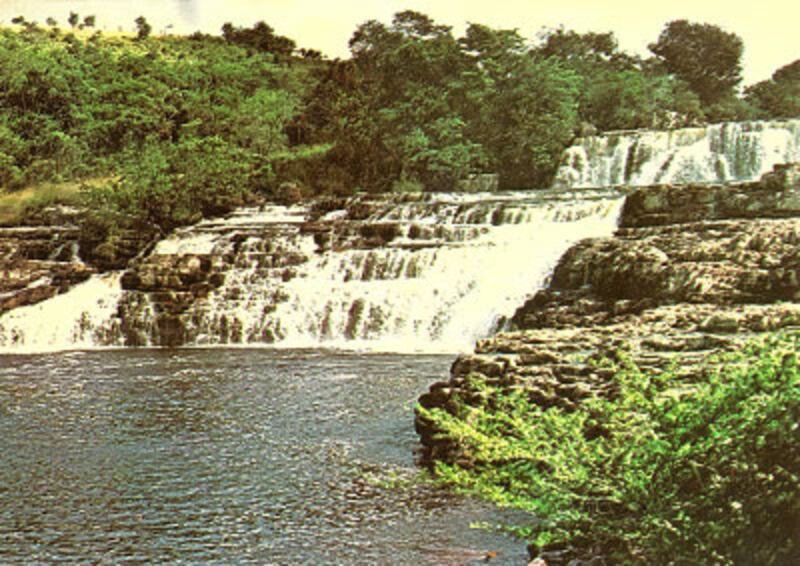

On November 24, the day after Thanksgiving, I found a post card on the floor mixed in with the pile of mail. The card displayed an unusually pretty picture of a waterfall and as I turned it over I saw Leo’s signature. He must have sent it shortly before he was killed. I think I screamed. My son was there—we were both stunned. The card began with, “This is NO [North] Guyana. No, I haven’t seen this.” and ended with “I don’t wish you were here though, Affectionately Leo.”

I still have it. And am probably the last person to have heard from him.

I never dealt with any of this. As I started to reflect on the last thirty years I decided to try to find some of the survivors, if there were any, to see what their recollections of Leo were in order to refresh my own. Seven people survived the actual massacre in the community. Four are still alive; I talked to two.

Most said they were burned out and had little to say, but once I told them I was writing about Leo Ryan they stared to unburden themselves, talked for hours as if to exorcise their ghosts.

The first thing I learned: the iconic phrase, “Drinking the Kool Aid,” is incorrect. According to Fielding McGhee of the Jonestown Institute, the lethal brew of cyanide and sticky, sweet punch that Jim Jones forced upon loyal followers that horrible day was not the traditional Kool Aid, but a British version which was labeled either Fla-vor-aid or Flav-R- aid. (McGhee is unsure of the exact spelling.)

“Leo was our only hope. Everything rested on him,” Vernon Gosney, a survivor who started the frenzy and ultimately the holocaust by slipping a note to a member of Leo’s entourage, told me. His note read: “Help. Get me out of Jonestown.” Gosney managed to leave Jonestown with Leo and was wounded at the same nearby jungle airport where Leo was assassinated. He is now a policeman in Hawaii.

Tim Carter, another survivor, breakfasted on pancakes with Leo along with all the other congregants in the massive temple pavilion on the morning of shooting. “‘Ingress and egress,’ freedom of movement was Leo’s primary concern,” he says. “I liked Leo Ryan. There was no pretension.”

“But,” Carter adds, “he did not realize the disingenuousness of Jim Jones.”

Carter escaped totally by chance as Jones’ acolytes were beginning their hideous demise. He and two others were suddenly assigned to carry three over-sized suitcases to the Soviet Embassy in Georgetown. Once he and his companions got permission to leave and were outside the gate, they dumped the suitcases and ran. Carter later learned they contained more than a million and half dollars in cash. He eventually settled in Oregon and is writing a book about his ordeal.

Stephan Jones, the middle of Jim Jones’ three sons, also escaped death because he was outside the confines of the community. He was in Georgetown, at the Temple headquarters with the Jonestown basketball team. Stephan met Leo when he first arrived in Georgetown from Washington en route to Jonestown. “He was everything my father was not,” he recalls. “I liked him right away. Straight, forward, kind and courageous.”

On November 18 Stephan got a coded message telling him to “get revenge,” and knew something was terribly wrong. “My father was such a coward, we had been through this kind of situation so many times before. I couldn’t contemplate he would go through with it.” Then he adds, “It’s clear my father came up against an honorable man who wouldn’t bail out in the face of danger.” Jones is now living in the San Francisco bay area where he sells commercial office furnishings.

Jackie Speier, Leo’s legal aide and companion on the fateful trip was the most crucial link, my lynch pin to the past. Shot shortly after Leo, she lay gravely wounded on the tarmac of the airport for 19 hours until the outside world responded to the crisis and a rescue plane finally arrived. She remembers Leo being shot, point-blank, trying unsuccessfully to hide, and calling out to him, but getting no response.

I went to meet her at her in her congressional office in Washington. A black and white photo of her late boss hangs on a wall. She was warm, outgoing, and intrigued with my post card. Extremely self possessed, she is a dead ringer for Allison Janney, the no nonsense press secretary of the TV series “The West Wing.” I liked her immensely and understood why she was Leo’s right hand and confidant.

Today she is participating in a ceremony in San Mateo, California, the heart of Leo’s district, to name a postal facility in his honor. Like many other witnesses, Jackie talks about his sense of invincibility. “He wanted to make things right, fix things, go where others would not go, he did not assess and did not understand Jim Jones.”

She speculates he would be in the US Senate, if alive today.

As for winning Leo’s congressional seat she shrugs and smiles. “I think he’d be proud I was serving my country.”

Then she skips a beat and chuckles, “I play by the rules more than he did.”

Sandra McElwaine is a Washington based journalist, who specializes in profiles and contemporary culture. She has been a reporter for The Washington Star, The Baltimore Sun, a correspondent for CNN and People and Washington editor of Vogue and Cosmopolitan. Currently she writes for The Washington Post, Time and Forbes.