Yes, you heard correctly. A museum in Germany has made a rather peculiar addition to its collection of art—a living re-creation of Vincent van Gogh’s ear.

The story most people have heard is that van Gogh, the painter responsible for masterpieces like Starry Night and The Potato Eaters, chopped off his own ear in a moment of psychotic madness (he was believed to have suffered from some form of mental illness). Recently, however, a newly discovered newspaper clipping suggests French artist Paul Gaugin may have been responsible, after the two came to blows one drunken night. Regardless of who wielded the blade, the ear has been resurrected and is not-so-quietly living at The Center for Art and Media in Karlshruhe, Germany.

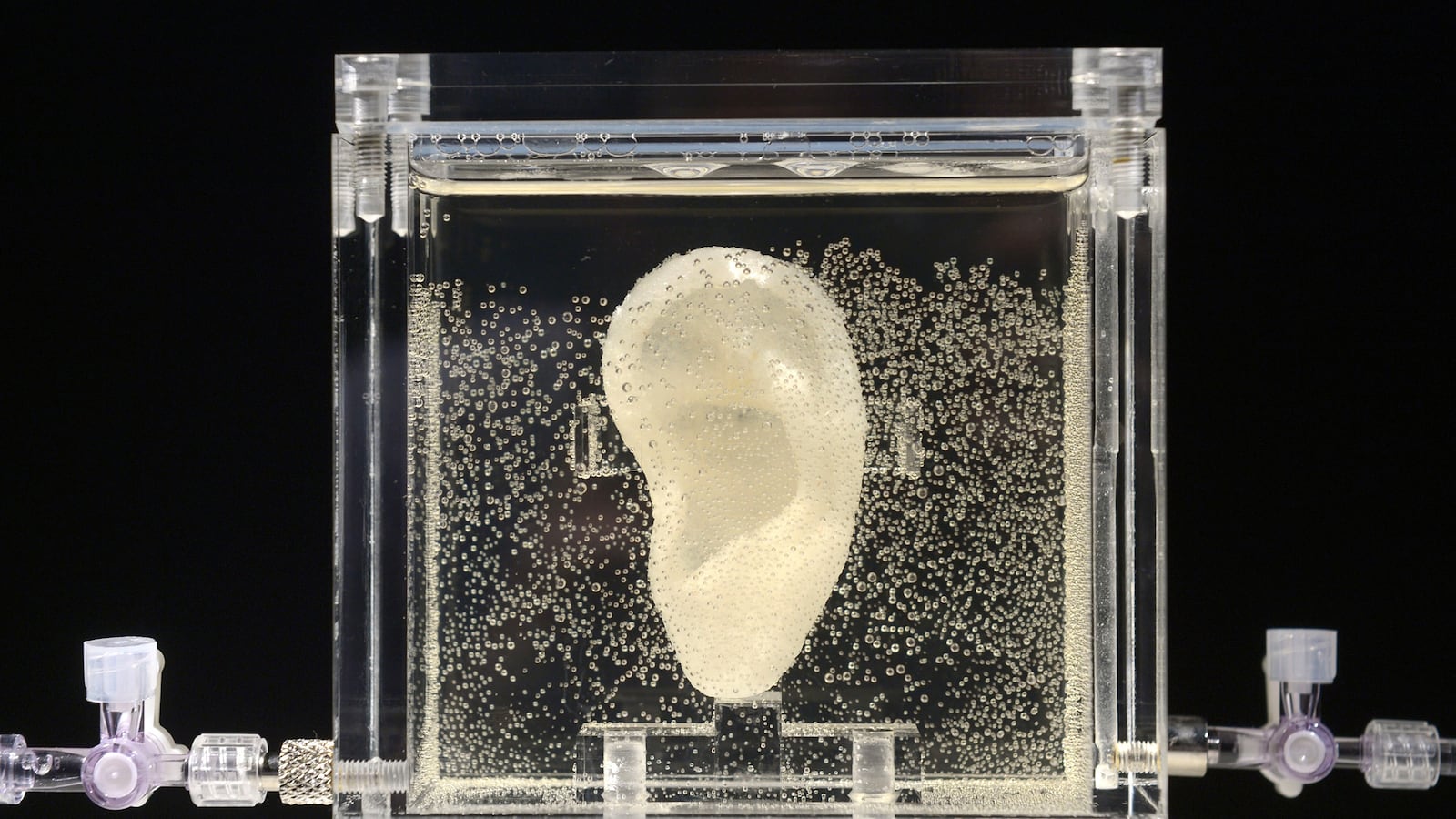

Forty-seven-year-old artist Diemut Strebe partnered with a team of scientists to grow a true-to-size replica of van Gogh’s ear, which hovers stagnantly within a transparent box filled with a nutrient-rich solution to keep the ear alive. “Sugababe,” as it has been aptly titled, garners its name from three parts of the building process. First, its color. “Second, the granular structure was a sugar-like thread that we used in the process of making the ear, the polymer,” Strebe told The Daily Beast. “And the [final] component is that ‘sugababe’ is the contemporary variation of Theseus’s paradox, which is actually the basis of all scientific approaches.”

Theseus’s paradox stems from an ancient philosophy originally known as the “Ship of Theseus,” which asked if a ship had all of its parts replaced, does it still remain the same ship? Here, “the famous paradox is carried out with biological material making a particular form of human replication, from historical or synthesized material, a central focus of this project.”

The Center is no stranger to science. In fact, its facilities house three research institutions—one for media, one for music and acoustics, and one for media, education, and economics—in addition to its two museums and media center.

All Strebe needed to create her living masterpiece was van Gogh’s DNA, which turned out to be easier to get than she expected. Strebe obtained an envelope used by van Gogh in 1883 from the Custodia Foundation in Paris and took samples of biological material from the stamp and once-sealed flap.

“DNA was extracted, a small part of the mitochondrial DNA was sequenced, cloned in vitro, and incorporated into living cartilage cells,” the exhibit’s press release explains. The living cartilage cells were acquired from Lieuwe van Gogh, the distant grandson of Vincent’s brother Theo, who shares 1/16 of the famous artist’s genome.

“Lieuwe van Gogh loved it right away,” Strebe said. “He traveled very quickly with me to Boston, and I presented to all my colleagues at Harvard and MIT, and he even gave them a piece of his ear to grow the [replica].”

Strebe’s colleagues are Robert Langer (MIT) and Charles Vacanti (Harvard), the duo responsible for growing a human ear on the back of a mouse in 1995. Lieuwe’s tissue provided an identical Y chromosome from an uninterrupted male lineage. Carried distinctly through men, the Y chromosome only gives a portion of the entire mitochondrial DNA. Strebe hopes to use a female relative for further renditions of the evolving installation.

The kicker is that the artistic piece, much like the ear that was once attached to van Gogh’s head, responds to human voices. Viewers are invited to speak to it through a microphone. The sounds then pass through the nutrient solution that sustains the tissue, penetrate the artificial ear, and play, as interpreted by the organ, over a loudspeaker.

Strebe isn’t the only artist working with genetic material. The “biodesign movement,” which “integrates living things, including bacteria, plants and animals, into installations, products and artworks,” most notably lit up the art world when its most radical figure, Eduardo Kac, successfully engineered a glowing bunny by injecting fluorescent protein from a bioluminescent jellyfish into an un-hatched albino egg.

Its grandeur received mixed reviews. Many animal rights activists—and a few scientists—called the creation unethical, while others praised Kac for “pushing the boundaries between art and life, where art is life.”

Other works by fellow biodesign artists include a flower spliced with human DNA, fabrics and self-portraits created from living bacteria, and even “bio-concrete”—a mixture of concrete and limestone-producing bacteria that grows over time to fill in cracks.

But, Strebe doesn’t indentify as a Biodesigner. It “doesn’t fit because I also work with quantum physics to make art,” she explained. “I have two projects going up to outer space—one of which is already at [the International Space Station].” The work, titled Jacob Climbed up the Sky, also “uses scientific concepts and grapheme (a sheet-like form of pure carbon)” to place a microscopic drawing on scotch tape and send it to outer space. The work “symbolizes the human urge to transcend and progress.”

Pretty cool, huh?

Sugababe is on display at The Center for Art and Media in Karlshruhe, Germany through July 6, 2014 and will travel to New York City next year.