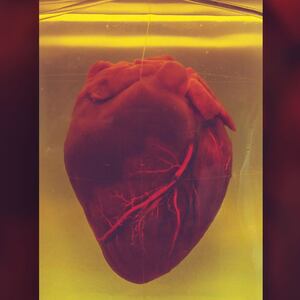

Since the first successful organ transplant in 1954, the idea of swapping a diseased or injured body part for a healthy one has revolutionized modern medicine. But one of the most persistent problems keeping organ transplantation from saving countless lives is availability. There are more people on the organ transplant waiting list than there are donors.

Part of the problem has to do with many donor organs not adequately meeting the criteria for transplantation because they’re too old or damaged. But another factor has to do with preservation: Donated organs don’t survive well outside the body, even when preserved on ice. Livers, for instance, can only be stored for up to 12 hours before transplantation, which is a limited time window to match the short supply of the much-needed organ to a transplant recipient. Luckily, though, this timeline might soon get extended by days.

In a study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Biotechnology, researchers in Switzerland created a device that allowed a donated liver to survive outside the body for up to three days before it was transplanted into a 62-year-old man suffering from severe cirrhosis and liver cancer. One year later, the man is still alive and his new liver appears to be doing just fine. The new preservation device, which builds off of an existing technology called ex vivo normothermic machine perfusion (NMP), may make collecting and storing organs from living donors more possible as well as decrease the chance of organ rejection and failure—a problem patients can encounter in the first years with their new organ.

For decades, the gold standard for preserving organs was to put them on ice. This method, called static cold storage, keeps organs alive and viable outside the body by slowing down their metabolic processes. But it can’t do it for so long—at some point, whether hours or days depending on the organ, the lack of oxygen renders it unusable to humans. That's why scientists developed NMP to get around this problem by storing an organ in a “warm” state where it gets blood and other nutrients continuously pumping into it, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine.

But even then, NMP has had limited success in keeping livers alive for more than a couple of hours outside the body. In 2015, the Swiss researchers of the new study embarked on an effort to improve the longevity of livers hooked up to NMP devices; in 2020, they managed to keep pig and human livers alive for up to a whole week. On top of that, the process appeared to improve the quality of the livers—some of which were damaged or considered poor quality—providing a seemingly nurturing environment that allowed the organs to naturally heal and repair.

However, the Swiss researchers needed to show that this setup could lead to a functional liver for an actual patient. The team procured a liver from a 29-year-old female donor who died in May 2021, and hooked it up to the perfusion device, which pumped a blood substitute through it at a normal body temperature. The fluid also contained additives like sugar, hormones to keep the liver’s glucose levels in check, and antibiotics to prevent any bacterial or fungal infection. A dialysis unit was also used to remove any wastes and keep the liver’s electrolytes in balance.

After three days on the NMP machine, the liver was transplanted into a 62-year-old man suffering from serious liver conditions like cirrhosis, or scarring of the liver, and hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer. The man recovered well from the surgery and was discharged from the hospital after 12 days. Since his new liver didn’t seem to show any telltale signs of organ injury or rejection on biopsy samples, the man was only on immunosuppressant drugs for six weeks, compared to six months to a year for many transplant patients.

One year later, the researchers report that the man still remains healthy and his new liver seems to be doing just fine. While the Swiss team cautioned further research with more patients and with longer observation periods is needed to see the full scope of the technology’s benefit, they are hopeful their new setup will help countless critically ill patients awaiting a liver. As the researchers write in the Nature Biotechnology paper, a new era of NMP devices that can keep livers and other organs alive for longer and possibly improve their quality holds the promise of opening “new horizons in the treatment of many liver disorders.”