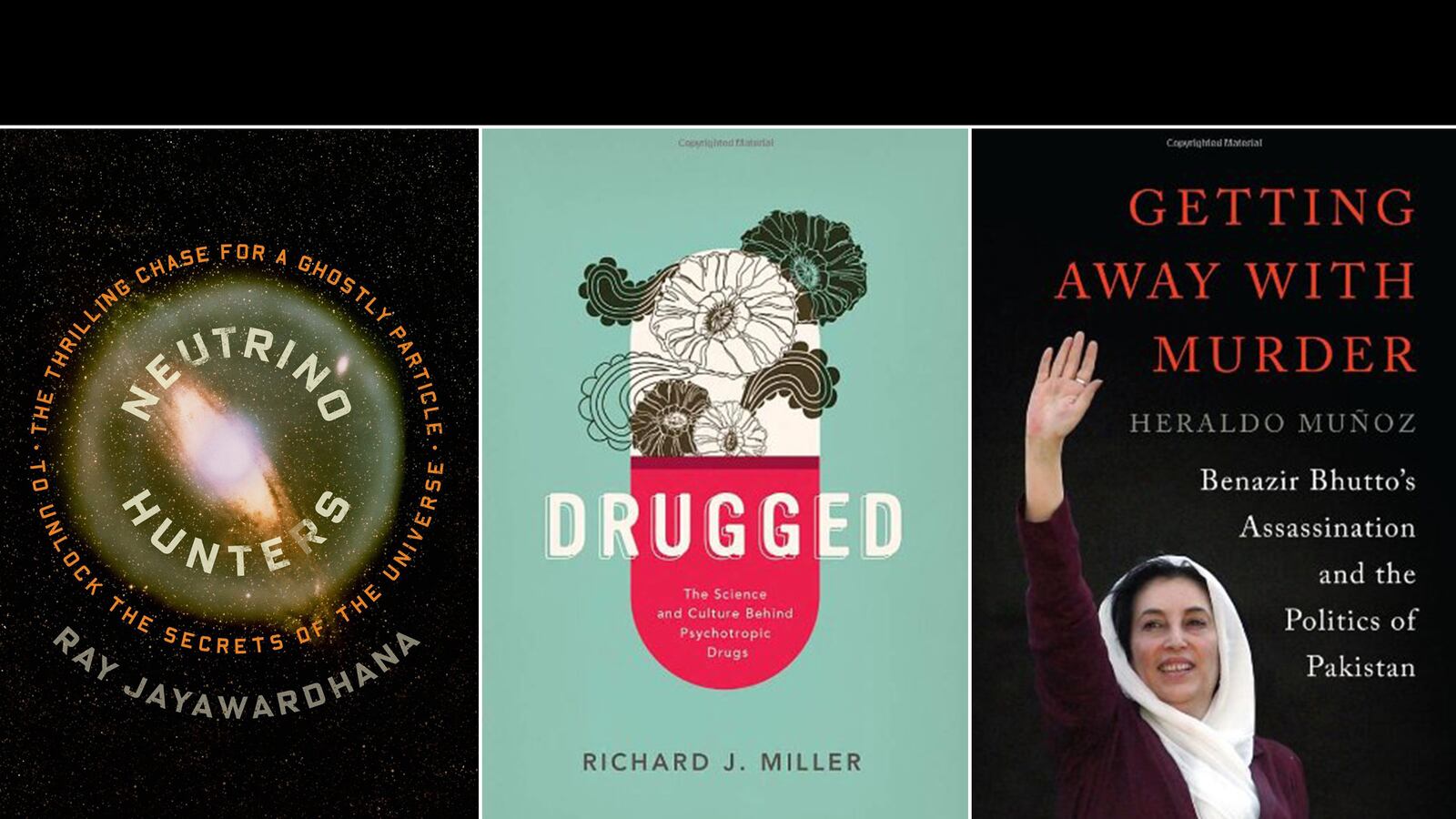

Neutrino Hunters, The Thrilling Chase for a Ghostly Particle to Unlock the Secrets of the UniverseBy Ray Jayawardhana

In an age of Google and NSA scandals, there seems to be no limits to our intelligence. The pleasure of Neutrino Hunters, by the astronomer Ray Jayawardhana, is that it reminds us how little we actually know, especially on the subatomic level. Since their discovery in the 1930s, neutrinos—elementary particles that carry a neutral charge—have generated increasing interest within the scientific community. They are the building blocks of matter, but unlike protons and electrons, their subatomic cousins, a neutrino can travel beyond the atom and pass straight through Earth without interacting with any other particles, “like a bullet cutting through fog.” This shyness has made the neutrino difficult to observe, and for scientists and theorists who believe these “cosmic messengers” contain the untold secrets of the universe, it also accounts for the thrill of the hunt. The story begins in 1930 when Austrian physicist Wolfgang Pauli theorized the neutrino into existence by way of explaining why matter went missing during beta decay, a dilemma that threatened to undermine Einstein’s relativity. A scientific hunt ensues to identify, trap, and understand what Jayawardhana calls galactic “poltergeists.” We encounter the bomb, exploding supernovas, and a giant cube designed to catch neutrinos in the wilds of Antarctica. The text is wonky at times, and if you haven’t cracked a physics book since high school, you may find yourself reading passages twice. Still, when it comes to neutrinos, the stakes are exhilarating: Why does the sun shine? Why do stars die? How did matter come to dominate the universe? It is a wonder to know there is still so much left to discover.

Getting Away with Murder, Benazir Bhutto’s Assassination and the Politics of Pakistanby Heraldo Muñoz

In 2009, Heraldo Muñoz, the Chilean ambassador to the United Nations, was surprised and honored to find himself tapped to lead an investigation into the assassination of former Pakistani prime minister Benazir Bhutto. Munoz knew little of Pakistan and reasoned that Chile’s apparent neutrality must have been a plus in the eyes of the U.N. as well as the Islamabad government. In short, Munoz was a diplomatic choice. So in a way it follows that his book about the investigation’s findings would strike a diplomatic note. Munoz paints a vivid portrait of Pakistan—the political violence, the rigged elections, corruption on every level—and complicates the circumstances surrounding Bhutto’s death with verve. But when it comes to drawing connections between nefarious outside forces and the nature of his mission, Muñoz remains polite. He refers to the trust deficit between Pakistan and the United States. He glosses over Britain’s colonial legacy as well as sectarian violence. He names Washington and London as “the key external players advocating Bhutto’s return to Pakistan … not willing to assume responsibility of her security,” but when he finds himself stonewalled by the foreign office in London after pressing them to disclose what measures they took to secure Benazir’s safe return to Pakistan, his tone remains ambassadorial. If their obfuscation had anything to do with the fact that Scotland Yard ran their own “narrow” investigation into Bhutto’s death, Muñoz never says so. In this way, the text feels veiled, an act of diplomacy in and of itself. By the end of the book, the circumstances of Bhutto’s death are as murky as ever. If the U.N. couldn’t get to the bottom of Bhutto’s death, at least they had shown the world they had tried to do something about it.

Drugged, The Science and Culture Behind Psychotropic DrugsBy Richard J. Miller

If you’re one to geek out over hallucinogens, it’s hard to imagine a more satisfying history than Drugged. A professor of pharmacology at Northwestern University, Richard J. Miller starts with the hunters and gatherers. He notes that “pharmacology came before agriculture” and locates the origins of religious experience in the consumption of magic mushrooms. From there Miller runs through history, taking into account the spiritual, chemical, and cultural significance of various psychotropics: the color mauve and the rise of the chemical industry; CIA initiatives involving LSD and mind control; the connection between Nazi rockets and antidepressants; pioneering psychiatry via peyote. Spliced into these chapters are others devoted to the chemistry and neuroscience of barbiturates, cannabis, Prozac, heroin, ecstasy, and other mind-benders. Here things get jargony, dense, and at times, indecipherable, with titles for sub-chapters like “Muscimol Becomes Gaboxadil,” “The Fall of Gaboxadil,” and “SSRIs Become SNRIs.” Miller’s prose can be equally tangled. Still, as an academic whose articles have been published in hundreds of academic journals, Miller’s enthusiasm gives the text a quirky, eccentric charm, as when he reveals his obsession for antique books, and shares a stash of letters and poems about laudanum, which he found in a London bookstore. Indeed, the connections Miller makes between the arts and the science of our brains on drugs are some of the most delightful bits in Drugged. Even if you can’t bear the chemical compounds, you can take pleasure in the 19th-century paintings.

Newtown: An American TragedyBy Matthew Lysiak

This is a difficult book to read. An opening letter by Monsignor Robert Weiss, a pastor at Saint Rose of Lima Parish, in Newtown, CT, sets the tone. “I stood in the midst of the purest love as I watched parents approach the casket of their child… to push back a lock of hair or place their child’s favorite toy for them to hug all the way to heaven.” We then meet the children who died. Newtown: An American Tragedy, by former Daily News reporter Matthew Lysiak, begins with vignettes of Charlotte Bacon, Jesse Lewis, Josephine Gay, and others, on the morning they were killed at Sandy Hook elementary in one of the most gruesome mass shootings in American history. The chapter is titled “Last Goodbyes.” There is value in bringing the victims to life on the page, and the experience, as a reader, is rightly hard. But Lysiak’s tendency to sentimentalize the children’s innocence is manipulative, exploitative, and undermines the credibility of his book, especially given that its publication coincides perfectly with the first anniversary of their deaths. Twenty-six children were massacred. Readers don’t need images of teddy bears and angels to grasp how tragic that is. In the pages that follow, Lysiak attempts to construct a portrait of the killer, Adam Lanza, the 20-year old gunman who, on Dec. 14, 2012, walked into Sandy Hook armed with a rifle and two pistols. Lysiak says he wants to understand why Lanza did it, but in suggesting that autism may be responsible, in spending 45 pages rehashing the gory details of what happened inside the school that day, and another 22 sharing heart-rending eulogies of the children, he only preys on fear and anxiety. In a chapter titled “Fog of War,” Lysiak describes how on that chaotic day the media got it wrong, including himself. He might take a page from his playbook.