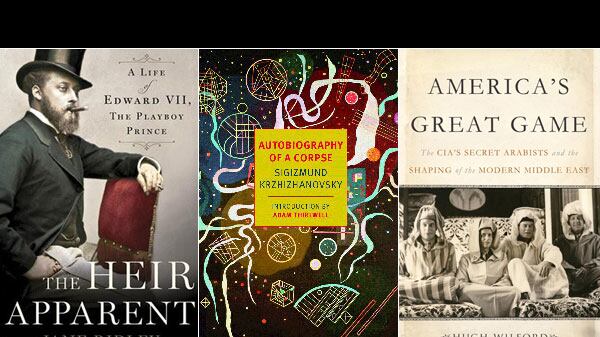

America’s Great Game: The CIA’s Secret Arabists and the Shaping of the Modern Middle Eastby Hugh Wilford

After Miles Copeland retired from his long career in the CIA, during which he helped organize the coup that overthrew the Prime Minister of Iran Mohammad Mossadegh, he developed a Risk-like board game in his new spare time. It was called The Game of Nations, and the description on the side of the box read: “Skill and nerve are the principle requirements in this amoral and cynical game. There are neither winners nor losers—only survivors.” America’s Great Game is professor Hugh Wilford’s gripping and witty account of American efforts to shape policy in the Middle East, in an attempt to avoid the mistakes that the British had made during their “Great Game” to control Central Asia. The picture he paints, though, is one more of failed good intentions then of imperialistic villainy. Copeland, and the two men of the Roosevelt line who he worked with, Archie and Kermit, were staunchly pro-Arab (and, in fact, anti-Israel), but in perhaps the quintessential story of tragic American over-reach, ended up installing dictators and regimes that were hardly helpful to the region. Although it’s a tempting analogy to make, perhaps it would be best to stop thinking of foreign policy as a board game.

When the introduction to a work of biography on an English monarch takes the time to specifically thank “Her Majesty the Queen,” it’s clear that you’re about to read the product of unprecedented access to royal resources. In The Heir Apparent, Buckingham University professor Jane Ridley (who has previously penned biographies of Benjamin Disraeli and Edwin Lutyens) sets out to reclaim the reputation of King Edward VII, who, as the son of Queen Victoria, had to wait nearly the entire 60 years of the Victorian era before taking the throne. During that time, he developed a reputation as a scandalous playboy (earning himself the nickname “Edward the Caresser,”) and Ridley uses his letters to various lovers and romantic rivals to colorfully confirm much of the gossip of the day. This required no small amount of reading between the Victorian lines on her part; for instance, an affair might be summed up in a letter as having someone over for tea several times. If “Bertie” (as his family called him, and as Ridley refers to him out of affection for her subject) deserved his reputation as a lothario, perhaps less deserved was his reputation as a disinterested and ineffectual king; Ridley makes an argument that, although he ruled for only nine years, his reign was an exemplary one. He had, after all, 60 years to prepare for it.

Autobiography of a Corpseby Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky

In his excellent introduction to the Autobiography of A Corpse, a newly translated collection from late Soviet author Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, British novelist Adam Thirlwell explains why you’ve probably never heard of the Russian before, and why he’s worth your time. To the former question, he simply had terrible luck: bankrupt publishers, Soviet censors, and the outbreak of WWII all conspired to halt various works of his that were scheduled for publication throughout his life, and it wasn’t until he died at age 63 and his papers were discovered locked in a trunk of his companion that he received posthumous attention. As to the question of why he still deserves to be read, these stories represent strong entries in two different traditions of Russian literature: firstly, the unhinged, feverishly experimental universe, in which a pianist’s fingers can detach themselves from his hand and flee down the aisle of the concert hall, or where a cold man on the streets of Moscow can remove a strip of paper from a notepad and jot something down, transmogrifying the paper into “lodgings measuring one hundred square feet.” Secondly, the grand woe of Dostoyevsky, in which is expressed the physic trauma of a frozen country so frequently torn asunder by ideology. Consider this sentence from the titular story, in which the narrator discovers a suicide manifesto reminiscent of Notes from the Underground: “I never suspected that the process of mental deadening could be creeping—from skull to skull, from an individual to a group, from a group to a class, from a class to an entire social organism.” What could be more Russian?

Heir to the Empire City: New York and the Making of Theodore Rooseveltby Edward P. Kohn

Think “rugged American outdoorsman” and one of the first names to come up will surely be Teddy Roosevelt: pioneering conservationist, gung-ho military man, and the bane of much of Africa’s stock of big game animals. It’s easy to forget that he was born not in a log cabin but rather as a New York City urbanite. In Heir to the Empire City, Edward P. Kohn aims to not only “shatter the mythology of Roosevelt as an untameable Rough Rider,” but to argue that some of his most important contributions to American ideas occurred in New York, where he served first as a state assemblyman and later as police commissioner, rather than in the wild west. Kohn’s prose is snappy and engaging, and his portrayal of the city, from the economic slump of the 1850s, through the Civil War, and growth of the avenues of corruption that it would be TR’s charge to cleanse, is as vivid as his evocation of the man himself. At under 300 pages, this is a tight and well-argued thesis, rather than a biographical tome, of which, for this great American, there may perhaps already be enough.