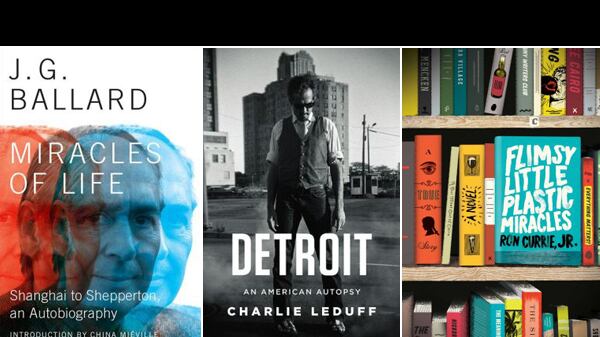

by J.G. Ballard

How the dystopian writer’s childhood in a Shanghai internment camp and his young wife’s death made him into the writer of ‘The Atrocity Exhibition.’

James Graham Ballard’s science fiction has no robots and no rockets, and the future and the present are equally dystopian. It mirrors French postmodernist Jean Baudrillard’s hyperreal—the simulacrum is not a copy but a truer world than our own. It folds and divides, jumps and tunnels. The mind of the protagonist of The Atrocity Exhibition is splintered by mass media, and processing pop-culture and public events like John F. Kennedy’s assassination and Marilyn Monroe’s suicide is as important as distinguishing between what is real and what is not. The people of his auto-erotic novel Crash coil sex, death, and the motor car, a megadose of pleasure brew. How did it come to this? Ballard’s autobiography, Miracles of Life, his last book, is illuminating. Available in the U.S. for the first time, the book tells the factual version of the fictional story that readers might know from the novel Empire of the Sun, or moviegoers might know from the Spielberg film based on it. Born in Shanghai in 1930, Ballard and his parents were interned at the Lunghua Camp when the Japanese invaded during World War II. (In the novel, Ballard writes his parents out of the camp, making young Jamie Graham even more alienated.) The hyperreal war switched on Ballard’s imagination, but it was another tragedy that yoked Ballard’s fictional world together. In 1955 he married, and he had three children, but in 1964 his wife, Mary, died suddenly of pneumonia. His writing became “a desperate attempt to prove that black was white, that two and two made five in the moral arithmetic of the 1960s,” Ballard wrote, as he tried to make sense of Mary’s death, the assassination of JFK, and the countless deaths of WWII into something meaningful. “Then, perhaps, the ghosts inside my head, the old beggar under his quilt of snow, the strangled Chinese at the railway station, Kennedy and my young wife, could be laid to rest.” Ballard died of prostate cancer in 2009.

—Jimmy So

There Once Lived A Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya, Anna Summers (translator)

Love stories scored to a totalitarian track that makes the mystery of love all the more murky.

Ludmilla Petrushevskaya writes instant classics. The Russian author composes little stories in black and white, immediately reminiscent of the tales of late Tolstoy without the moralizing—which is another way of saying she sounds like Chekhov. Her matter-of-fact voice makes the resemblance unmistakable: “A Murky Fate” begins with “This is what happened.” “So here is the setting,” she announces in “The Fall.” The omniscience draws attention to the Soviet authority; in “Father and Mother,” neighbors advise the matriarch to go to a Party supervisor if she wants to accuse her husband of infidelity, instead of making a scene every day. Petrushevskaya is best at the pas de deux, where women and men stick together and peel apart due to some mysterious force. In “A Murky Fate,” an unmarried woman in her 30s asks her mother to leave their apartment so she can bring home a fat, diabetic lover. In the very Updike-like “The Fall,” a woman with “atrocious” heels and “ridiculous” curls mellow and loosen during a vacation as she falls in love with a tall man nicknamed “Number One,” but they will soon be “deceived by the promise of eternal summer, seduced and abandoned.” In “Father and Mother,” not even the eldest daughter knows how and when her absurd parents, who fight constantly, manage to have almost a child every year, as closely as she watches them. These, as the title proclaims, are love stories, scored to a totalitarian track that makes the mystery of love ever more murky.

—Jimmy So

by Charlie LeDuff

A Pulitzer Prize–winning writer embeds himself at home in the Motor City.

Detroit is a lot of things to Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Charlie LeDuff: crippled, poverty-stricken, corrupt, dangerous ... home. And his third book balances those stories in a unique, heartbreaking love letter to a city nearly forgotten.

LeDuff returns to the Motor City—a place he and 1.3 million people once called home—to find that the collapsed economy and years of neglect have left the city dead: devoid of jobs, bled of nearly half the population, and unresponsive to the spreading of its own wounds.

But for LeDuff Detroit is also the hometown of his great-grandfather, the place where his mother’s flower shop once stood, the place where his sister’s drug habit made her another statistic. So he goes to work examining the remains of the city and shares candidly what passes for a normal day in Detroit: excavating bodies frozen feet-up in abandoned elevator shafts, watching firefighters put out blazes and then scrounge the wreckage for anything to fix up their crumbling firehouse. LeDuff refuses to let us turn our heads from hard images in a town where schoolchildren bring their own toilet paper, where ambulances come too late if at all, and where even the undertaker is taking advantage of people who have nearly nothing.

And though he is the focal point of his own narrative, LeDuff isn’t trying to befriend his readers, nor does he want their admiration. Equally honest are his appraisals of his hometown, his family, and himself. But eventually that admiration comes, not for the little bits of reportorial heroism, nor for his acts of charity for the desperate and the deceased, but for his determination to do what so many in his book and Detroit do every day: stick around, survive, and hope.

—G. Clay Whittaker

Flimsy Little Plastic Miracles

by Ron Currie Jr.

A novelist escapes to the tropics after tragedies begin stacking up at home.

How far will you go to escape it all? For Ron Currie Jr., there are plenty of answers: to the liquor store, to an isolated tropical island, and even to faking his own death.

Alcohol, fistfights, and an emotionless fling with a co-ed keep the bad feelings at bay while narrator Ron Currie (who shares a name with the author in a postmodern haze) waits in his tropical purgatory, sent away by Emma, the only girl he’ll ever love, in yet another of her sudden changes of heart. His relationship with Emma swerves erratically between extremes, one minute allowing us to peer into a hair-ripping, blood-drawing moment of intimacy, and the next navigating an iceberg field of passive text messages. Eventually Ron hits bottom, attempting suicide but failing to finish the job. But enough people believe the job to be done that his newly finished manuscript takes on posthumous hype and becomes a wild success, forcing him to decide whether to return from the dead.

The novel’s untraditional, stylized pacing is expertly executed, delivering a story equal parts dark humor and unpreventable tragedy. His narrator’s scatterbrained story yanks us from flashback to flash forward to philosophical tangent about the imminent creation of artificial intelligence, promising his reader nothing but “capital-T Truth.” His constant and circular deconstruction of Emma allows him to shrug off other sources of misery—his father’s recent death and the destruction of an overdue novel manuscript in a house fire. The result of this is a narrator who gets sympathy, even when he gets what he deserves.

Sharp and sarcastic, Currie’s dramatic story keeps you tethered in place, letting the world spin in orbit while his voice gently directs the tour. It’s a truly genuine love story wrapped in a series of comically improbable events.

—G. Clay Whittaker

by Charles Dubow

A riveting read best enjoyed on the uncluttered beach at the Maidstone Club.

It’s been decades since the barbarians stormed the hedgerows; but Charles Dubow, a journalist who spent childhood summers on Georgica Pond, is still wistful about that genteel Hamptons landscape, now wrecked by vainglorious newcomers. His debut novel is a cultural lament wrapped in a lesson about extramarital lust—a riveting read, in other words, best enjoyed on the uncluttered beach at the Maidstone Club. (Here I should add that Dubow is a friend and a former colleague at Forbes.)

Dubow’s narrator, Walter, could be compared to Nick Carraway, but there's no parvenu Gatsby in his life. Walter’s neighbors are his lifelong friends Harry and Madeleine Winslow, whose summer cottage exudes dilapidated gentility—it is “lived in, loved ... its shingles brown with age.” Walter’s place is an enchanting pile that today’s Realtors would tear down and rebuild with a media room. The three friends, old-guard insiders, are all aging tastefully.

Walter has been quietly in love with Maddy since their New Haven days. A self-deprecating bachelor, he is also an unapologetic snob who, when martini time rolls around, can “drop the ice cubes into an old Cartier silver shaker that belonged to my grandfather.” Just as he deplores the vulgarization of Newtown Lane, he's an emotional preservationist, respectful of the institution of marriage.

But Harry, handsome ex-Marine and feted author, is greedy for more happiness than Maddy, a WASP goddess, gives him. Enter Claire, a beguiling young publishing wage-slave, who, drawn in by the trio’s hospitality, swiftly dumps her shag du jour, a British banker. Her new, old-moneyed friends are not “impressed by his Aston Martin ... or the last time he was in St. Bart’s.”

Expensive real estate is an aphrodisiac for girls like Claire, Walter notes. And as this novel tells us, so is an accomplished older man in a seemingly idyllic marriage.

—Tunku Varadarajan