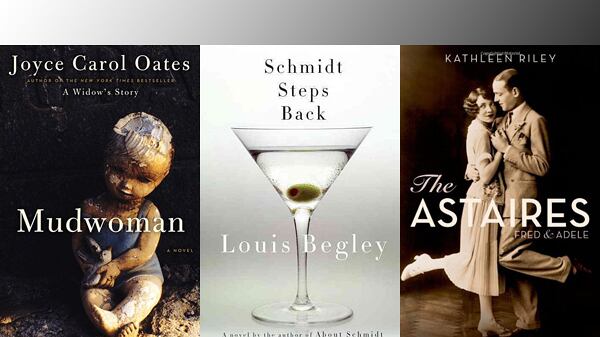

The title is perfect, not only for Oates’s latest novel—her 38th, in case you’re counting—but as a summary of her American Gothic oeuvre.

“Mudgirl” was left to die beside the Black Snake River. She is rescued and adopted, like Moses, and grows up to be “M.R.,” perhaps as masculine as initials come, and becomes a philosopher who’s also the first female president of an Ivy League school. (Oates is herself a professor of humanities at Princeton.) But however high you rise and however wide the wooden halls that you walk down, you’re always in danger of sinking and becoming enveloped in the sludge from which you sprang.

A former Marine and ‘The Wire’ actor files a tunneling, psychological report on the War-in-Iraq experience, for the War-in-Iraq generation.

Officer Colicchio in The Wire always looked as if he would pull out his service weapon and empty his clip on the hoppers at the corner, so enraged was he at the “moral midgetry” of it all. The man who played him, Benjamin Busch, served two tours in Iraq for the Marines and was twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize. He, too, is mired in the seductiveness and consequences of macho violence, and delves very deeply into the matter—so deeply that at times you wish he would lighten up and put down the things he carried. (Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried being the book that Dust to Dust is being compared to.) But Busch hasn’t only written a memoir about war; the journey also takes him to the heart of family, and yields gems like this: “My parents’ home is now a museum to my memory of them in it. No one to greet me at the door. No warmth inside. Nothing cooking. Just the things that they had collected in a life together and a history of things that I had given them all preserved within a tomb that holds no remains but what remains.”

The way Fred and Adele Astaire glided and strode on stage must have reminded one of the joys of being alive. The first major biography of the duo reaches across almost a century and touches the thin hint of a partnership that’s in danger of disappearing entirely.

“Speaking about dance is like nailing Jell-O to the wall,” or so the saying, sometimes attributed to Merce Cunningham, goes. But writing about a dancing duo that was never filmed is like trying to nail the Jell-O from the next room. How do you put together a book about the “purportedly superior alchemy” and the “famed sparkle” of Fred and Adele Astaire, whose public performances have never been recorded cinematically? The thirst must be as great as the yearning for Paganini’s frenzy or Nijinsky’s leaps. The answer is that Riley is an impressive research historian, and she relies on a considerable amount of quotes from those who saw them on stage, the last instance of which happened 80 years ago. It’s a minor felony that no biography of Adele exists that's written by someone fortunate enough to have seen her perform seriously, if only to remove the “purportedly” from sentences that might otherwise have imitated the snap and sting of “Fascinating Rhythm.” Look ma, I’m dancin’! Feelin’ good, lookin’ swell!

When I Was a Child I Read Books: Essays

Some writers command such confidence and devotion that you’ll gladly follow their snaking sentences, wherever they may lead, on topics as varied as childhood reading, the influence of Moses, and the freedom of thought.

It matters little what Robinson is writing about or where she’s going. She might begin an exploration of “Austerity as Ideology” with the fact that craters are named after Machaut and Derain on the planet Mercury: “More detail has been added to our universe, to the map of what we know in the very human ways that we know it.” She might preface her new collection of essays with a Walt Whitman passage, go on to examine democracy and law throughout Protestant history, and conclude by bemoaning that “we have slack and underfinanced journalism and the ebbing away of resources from our universities, libraries, and schools.” Where she ends up also matters little. Her thinking is so bright with clarity, her phrasings so handsomely sweetened, that tailing her upriver is one of the great pleasures in life.

Schmidtie is the Rabbit Angstrom of the post-Updike era, and there’s hope for him, yet. He loves the new president-elect (it’s 2008) and a lady from Paris is coming.

“New Year’s Eve, eight o’clock in the morning.” That’s the first sentence of the new novel about Schmidt, who is 78. (About Schmidt you’ve heard of, thanks to Jack Nicholson.) It is the dead of winter, at the very limit of the year, and though it is not Jan. 1 (who else but an old man would be up at eight on that morning?) it is still an early start to a lazy day. But the effect of ambiguity is produced by the promise of a fresh start—a new year!—and the smell of dawn. (Begley goes on talking about a nation that had overcome its history and was sending Barack Obama to the White House.) The sly, sneaky opening recalls the start of Gay Talese’s spectacular profile of Joe DiMaggio, another man well past his prime: “It was not quite spring.” At 78, Schmidt is looking for redemption and cleansing, and, like DiMaggio, comedy and poignancy achieve a perfect balance. Masters of prose can cut a pretty slit through that membrane of imagination and open out a world like that.