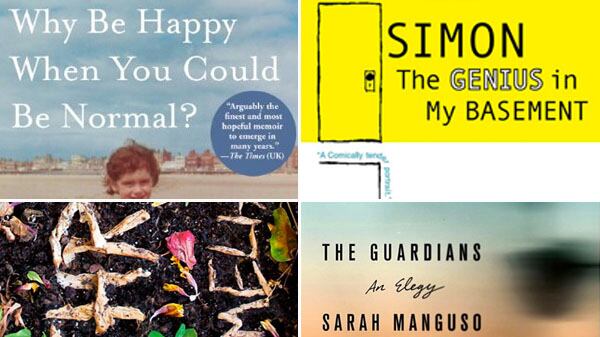

The Guardians A harrowingly elegiac memoir to a troubled friend who killed herself—and a search for just what they shared.

Halfway through Sarah Manguso’s haunting elegy to her friend Harris, who escaped a psychiatric facility and threw himself under a Metro-North train, she writes, “At first I thought a death was a thing in itself, a discrete item in the world, a piece of time and space.” The Guardians is the story of how she came to learn otherwise, to see how a death can reverberate across years and bind itself up in the living.

Although Harris is the subject of the work, it is Manguso who is really on display here, vivisecting her grief for the reader with a poet’s grace. More than either of them, though, the real main character is their relationship itself; urgent, awkward, and beautiful. Perhaps nearly as tragic as Harris’s death is the loss from the societal lexicon of the idea of romantic friendship. Without it, language struggles to properly describe what they shared.

Part Joan Didion and part John Donne, Manguso has the rare ability to devastate and illuminate with a single sentence. In just over 100 coruscating pages, she seems to tell all that could possibly be told about the intersection of her life with Harris’s, and the spiritual forces that that intersection created.

Simon: The Genius in My Basement What is a writer to do when he finds out that the strange recluse in the basement is a brilliant mathematical genius?

It seems a stroke of almost unbelievable good luck for a writer whose first book was a well-received quirky biography (Stuart: A Life Backwards) to discover that he lived above the basement home of a reclusive mathematical genius, but that was precisely the situation Alexander Masters found himself in. His landlord, Simon Norton, helped pen one of the most influential mathematical works of the last century but, like all good geniuses, lost interest in his own brilliance, and now spends his days poring over public-transport timetables, which line his “excavation” (Masters’s word for Norton’s cavelike abode) in moldering drifts.

Simon: The Genius in My Basement is really two books in one. The first is the human story of Masters’s relationship with the prickly Norton, which is by turns touching and contentious, and the other is a fun and relatively easy-to-grasp examination of the mathematical ideas that made Norton a wunderkind, accompanied with Masters’s own illustrations. Even if the reader has no interest in math, the other half of the book is still fascinating reportage on a beautiful mind that has not quite come unhinged, but simply moved on.

Threats It begins with a husband holding the body of his wife …

Amelia Gray’s Threats begins just where you might expect a doomed, macabre love story to end: with husband David sitting on the stairs holding the body of deceased wife Franny for three days. Soon after, while deciding whether he can trust the detective assigned to the case, he begins to find threatening messages that show a flair for the creatively eerie, hidden in the crevices of the house. An example: “I WILL CROSS-STITCH AN IMAGE OF YOUR FUTURE HOME BURNING. I WILL HANG THIS IMAGE OVER YOUR BED WHILE YOU SLEEP.” Racing against his own rapidly diminishing mental facilities, David must solve the mystery if he has any hope of finding some sort of internal peace. He flees the bleak landscape of his reality into lyrical flashbacks about his time with his wife, but they offer less and less respite as the novel nears its feverish conclusion.

This is profoundly creepy, not-to-be-read-before-bed type of stuff, and there are more than a few Palahniuk-style gross-outs that will delight a certain kind of reader. An atmosphere of paranoia and decay hangs over each scene, but Gray still manages to inject some humor in a Tim Burton–esqe way, only darker. Most impressive, though, is that at the core of this freak show lies an oddly touching, original story of a love so singular that it could only seem crazy.

The UndeadWho cares what happens after we die? A veteran science writer conjures up the weird and frightening things that happen to our bodies.

We may think that of all the maladies that can be visited upon the human body, death itself would be the easiest to diagnose. Not so, says veteran science writer and editor Dick Teresi in his new book, The Undead, which explores the various methods that societies throughout history have used to determine that someone is indeed well and truly dead, and the ways that modern science (and some dubious methodology) has moved us toward a “brain-death”-centric model that should, Teresi argues, give us pause.

Certainly most unsettling is the idea that doctors in the last 100 years have pushed for a less stringent definition of death in order to harvest our sweet organs for transplant. For instance, if you don’t want your organs donated, Teresi recommends that you “Don’t die in DC,” where a law allows doctors to “pre-harvest” your organs while the hospital searches for your family to gain permission to donate the organs that it's already prepared.

The Undead is part physiology and part philosophy, and there are reflections on the nature of personhood and how to define when, exactly, “whatever it is that made her ‘her’ isn’t there anymore.” Teresi presents himself as merely a journalist illuminating truths, but in fact he makes a strong case for a reexamination of how we treat the shuffling off of our mortal coils.

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?From British novelist Jeanette Winterson, a memoir about her abusive childhood and escape into books.

It’s a common phenomenon in both fiction and reality for a child in unhappy circumstances to escape into books, and so begins bestselling author Jeanette Winterson’s memoir, titled Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?, when the author accidentally discovers her first lines of T.S. Eliot and begins to cry.

The driving force of her need to discover worlds outside her own is her domineering and religiously dogmatic adoptive mother (referred to as “Mrs. Winterson”), who plays true to bibliophobic type, at one point saying, “The trouble with a book is that you never know what’s in it until it’s too late.” Mrs. Winterson, though, is not a cliché, and the memoir treats her fairly. She is at the same time the story’s villain, its most sympathetic character, and, in her Dickensian Britishness, its comic relief. It is she who utters the titular line, when Jeanette explains that she is in love with another woman simply because she makes her happy, and a picture emerges of Mrs. Winterson as a woman victimized by her own repressiveness as much as she victimizes others.

The book continues on to deal with Winterson’s literary and sexual awakenings, her education at Oxford, and her attempts to reconnect with her birth mother, but the narrative never escapes the shadow of the exquisitely cruel Mrs. Winterson. It’s the element of redemption and forgiveness twice over, one for each mother, that makes this such a compelling read.