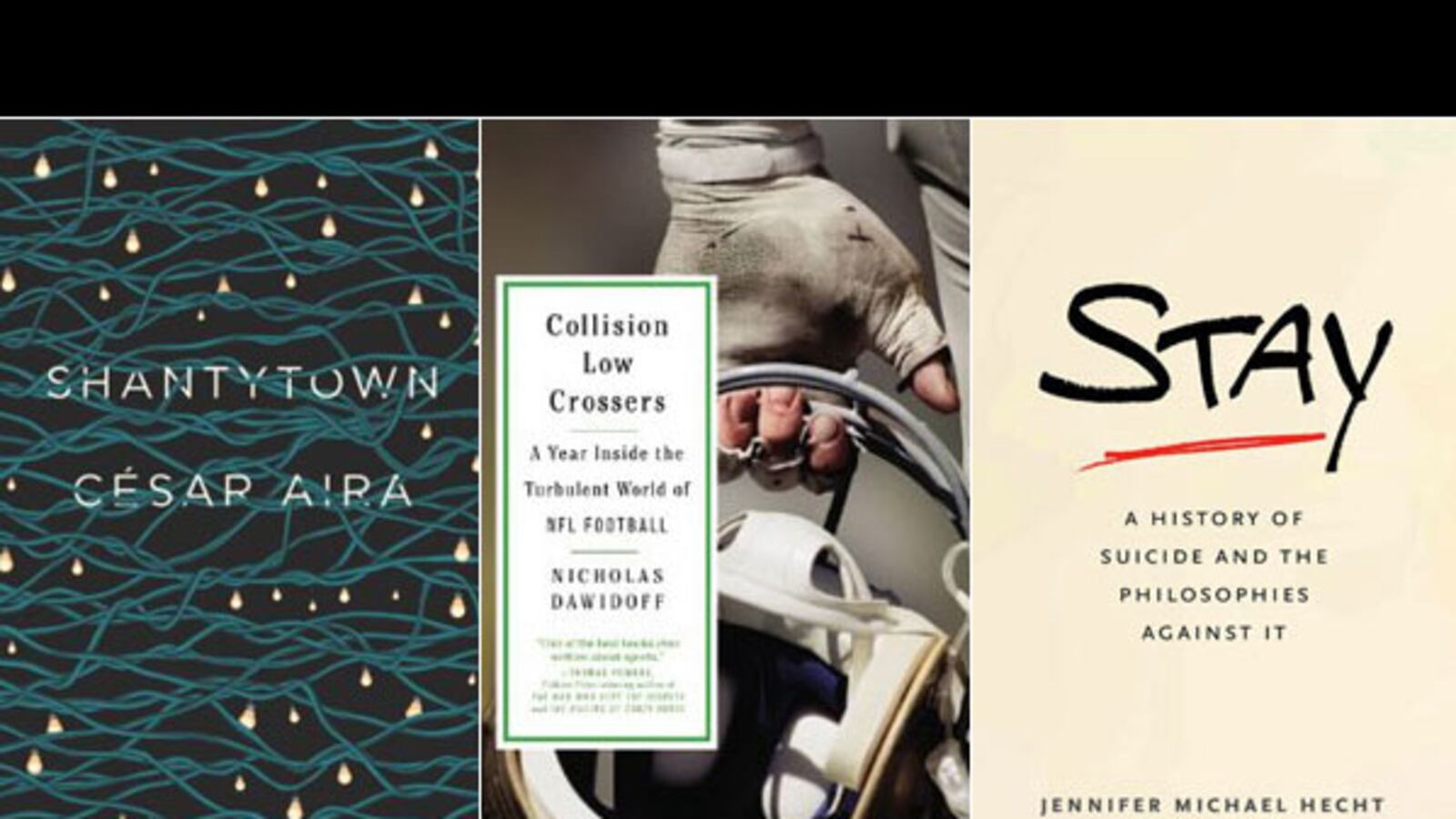

Collision Low Crossers: A Year Inside the Turbulent World of NFL Footballby Nicholas Dawidoff.

As we learn more about the long-term effects of concussions on retired players, their Faustian-bargain has become harder and harder to ignore on Sundays. Nicholas Dawidoff’s Collision Low Crossers: A Year Inside the Turbulent World of NFL Football is a timely book. Embedded with the New York Jets during the 2011 NFL season, Dawidoff details just how much the players and coaches sacrifice for the game, both in terms of physical wellbeing and sheer devotion of time and effort. In a league where the difference between the best and worst teams is small, football demands constant, fanatical preparation to compensate for the parity. Though the New York Jets have a reputation for being a chaotic and underachieving team, Collision Low Crossers reveals how much competence and hard work can go into an underwhelming 8-8 season. At the center of the drama is head coach Rex Ryan, a football Falstaff whose outsized girth and charisma belies his football intelligence and single-minded devotion to the Jets. Memorable as well are the two superhumans on the Jets’ defense, Darrelle Revis, the taciturn star of the secondary whose peerless skill and work ethic are notable even among professional athletes, and Antonio Cromartie, the mercurial head case who is only occasionally transcendent. Most poignant, however, is Dawidoff’s portrait of the countless fringe players who make up the majority of an NFL roster. These minimum-contract role players are constantly battling to keep their jobs, knowing that an injury, a mistake, or simply getting older will put them on the couch on Sundays, never to play NFL football again.

Shantytownby César Aira.

The remarkably prolific Argentine writer César Aira has published ten books since 2010, but only a fraction of his surreal metafiction has been translated into English. Shantytown, a crime novella first published in 1998, is the latest. In Shantytown, the titular slum of Buenos Aires is the backdrop for a series of killings that threaten the entire community. The shantytown operates as a delicate ecosystem of poverty and co-dependence, created out of necessity by its residents who haul garbage for a living. Aira’s depiction is wonderfully specific; the residents of the shantytown, because they steal their electricity, use it to excess, lighting the entire, labyrinthine ghetto. The eerie light, however, does not illuminate the mystery at the heart of the novel, a killing that brings dirty cops, drug dealers, and affluent interlopers to the neglected ghetto. Shantytown succeeds both as a compelling modern noir and a revealing depiction of life in the third world.

Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against Itby Jennifer Michael Hecht.

This is a history not only of suicide, but how we think about suicide. The Stoics considered it a final act of noble suffering, but Plato thought it fundamentally detrimental to a civilized community. Schopenhauer called it invariably a “mistake.” Thomas Aquinas’s view that suicide “violates our duty to God” was the position of the Christian church for centuries. Dante reserved the innermost circle of hell for Judas, Brutus and Cassius; for all three, their betrayals were compounded by their self-inflicted demise. During the Enlightenment, David Hume argued that suicide was a right of the individual, a reaction against Christian dogma that would come to dominate modern philosophy. Indeed, what we think about suicide is inextricably a product of what we think about God. Whether one believes in “that undiscovered country” that Hamlet so eloquently contemplates is critical to whether one believes that suicide is a sin or an elemental right. At the end of Stay, Hecht proposes her own argument against suicide in the secular, modern world, presenting a humanist call for life that can be separated from the mires of religious debate. Her final plea to the suicidal gives the book its title: she urges them to simply “stay.”

Pinkerton’s Great Detective: The Amazing Life and Times of James McParlandby Beau Riffenburgh.

In the 19th century the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, a private security firm, had more active agents than there were members of the United States Army. Greatest among these was James McParland, a man whose renown as a lawman was such that he inspired one Sherlock Holmes story and appeared in another. That McParland would be fictionalized was inevitable; as a relentless self-mythologizer, he had been fictionalizing his exploits for his entire life. In the new book Pinkerton’s Great Detective: The Amazing Life and Times of James McParland, Beau Riffenburgh separates the man from the myth, revealing the true and still unbelievable life story and clandestine exploits of this remarkable American original. McParland’s questionable legacy, along with the still extant Pinkerton’s, is made more troubling by his frequent association with ruthless anti-union corporations that hired him to disrupt to labor organization. Indeed, McParland’s greatest triumph as a detective—an undercover infiltration into the Molly Maguires, a group of rebellious Pennsylvania coal-miners—seems to modern eyes less a swashbuckling adventure than a gross miscarriage of justice that sent 20 men to the gallows to serve corporate interests. Riffenburgh navigates this moral quagmire deftly, contextualizing McParland and his far more violent time, while simultaneously deconstructing the image of the “Great Detective.”