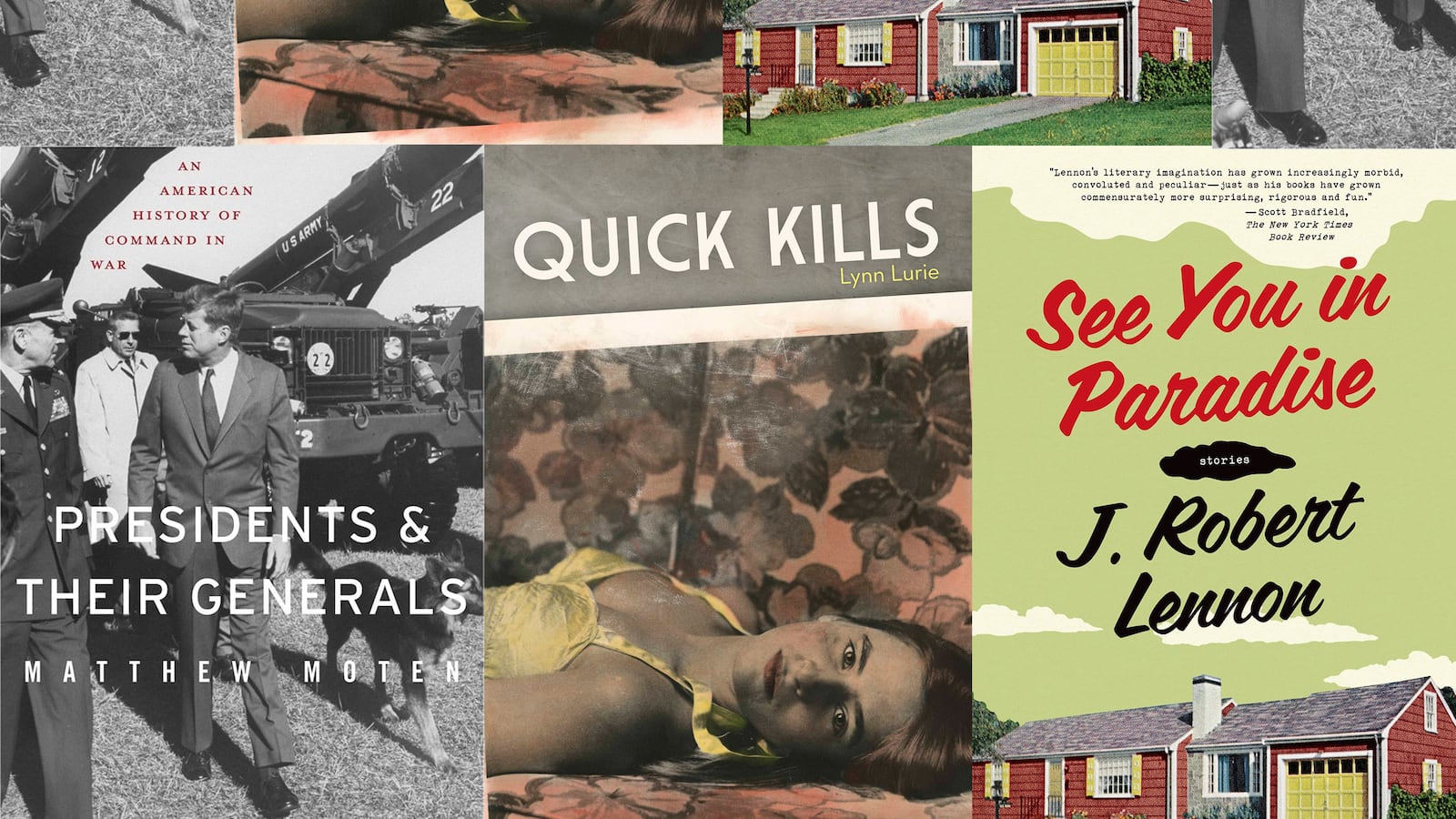

Presidents and Their Generals: An American History of Command in Warby Matthew Moten

Shortly after President Truman relieved General MacArthur of his command in Korea, the old God-General stood before a full session of Congress and millions of Americans watching at home to deliver his famous “Old Soldiers” speech to rapturous and ceaseless applause. The president himself, however, had a different review of the oratory: “It was nothing but a bunch of damn bullshit.” In Presidents and Their Generals: An American History of Command in War, Matthew Moten, former head of the Department of History at West Point, gives a masterful analysis of the evolution of the American system of military command, in which exists a remarkable cloistering between the military men and the political apparatus that delivers them their orders, and the ways in which that system has so successfully maintained itself. He begins, naturally enough, with Washington’s creation of the nation’s first standing army and subsequent refusal to be deified. Then come the echoes of that precedent through 11 more chapters detailing the professional lives of other American titans. These include John “Black Jack” Pershing, who wielded almost complete power to wage both war and politics in Europe during World War I before being reined in by Woodrow Wilson; and MacArthur, whose power and prestige after World War II was unprecedented for an unelected American leader, and, upon his homecoming, dangerous to the very foundations of the American political order. This book is an incredible work of American history, blending as it does military and political histories while simultaneously addressing a will to power that is as American as it was Roman. While not light reading, this indispensable work contains within it a picture of America that expands beyond its subject matter.

Quick Killsby Lynn Lurie

Quick Kills, the second book from Lynn Lurie (Corner of the Dead), is packaged as a novel, with the word “fiction” printed right there on the back cover for the ease of librarians, and so that is how it deserves to be discussed. But Lurie so effectively conjures an uncomfortable familiarity with pain and shame that one would be forgiven for assuming that the book is a memoir, reminiscent of Frank Conroy’s Stop Time. The book also refuses to conform to conventional novelistic style. In small episodes of often little more than a page, the narrator unveils to the reader image after image of her dysfunctional upbringing and an inappropriate, abusive relationship with an older man she calls “The Photographer.” A traditional plot never emerges, but much like James Salter’s masterpiece A Sport and a Pastime, none is needed. The images speak loudly enough: “In the photographs he takes that afternoon, I am naked in an abandoned swimming pool. Rainwater has collected at the deep end and last year’s dead leaves float across the surface.” But unlike Salter’s book, powered as it by love or at least lust, a much darker coil of violence underlies each page here. “The Photographer works in the dark, manipulating the shadows, reconfiguring my image, staring at me as I emerge from the red plastic pans filled with chemicals. He moves my head to another person’s body, dangles it from a tree branch.” This book being fiction, one is tempted to recommend it on some kind of Haloweenish merit, for its ghoulish ability to disquiet, but that would seem almost to disrespect the characters Lurie has rendered so realistically here.

See You in Paradiseby J. Robert Lennon

In the first story in See You in Paradise, new collection by J. Robert Lennon, a family discovers a shimmering portal in a clearing in a lot behind their house, through which they embark on all sorts of adventures into various other realms, worlds of odd creatures and endless fog and sickly robots, until the family tires of it and moves on with their suburban malaise. The reader assumes, then, that the rest of the collection will be of that same recognizable genus of story, in which something odd or impossible is affixed to the more quotidian lives of the characters to serve as interesting analogy or metonymy. But the fun of reading Lennon is in his outright refusal to conform to expectations. The second story is pure American realism, in which two couples who both wish to adopt the same child joust passive-aggressively or just aggressively during a façade of a dinner party. Other stories are somewhere in the middle. In “Hibachi,” a disabled man gifts his wife a full hibachi grill and watches as she turns into a sinister culinary master; and in “Zombie Dan,” a group of friends deals with the medical resurrection, a common occurrence in this near future, of someone who they never quite liked in the first place. And in “The Accused Objects,” Lennon empties a notebook’s worth of seeds for full-length stories but lets the reader do most of the work himself: “A biscuit crushed into the slush of a Kentucky Fried Chicken parking lot…Acrid mist that, not long after a crash is heard from the chemistry storeroom, begins to seep out from under the closed door…A white glove worn through just below the second knuckle of the fourth finger, where she tapped her wedding ring for many years against the brass studs of the armchair.” In Lennon’s rule-breaking fictive universe, one is never quite sure in which direction a story is headed or which character in that story is the main subject, and the result is a pleasurable tension rarely found elsewhere. This book is a virtuosic performance in original and tricksterish storytelling.