WARSAW—Forbidden meetings, unanswered phone calls and thinly veiled threats. What was supposed to be the beginning of a beautiful friendship turned into the most serious diplomatic crisis in decades.

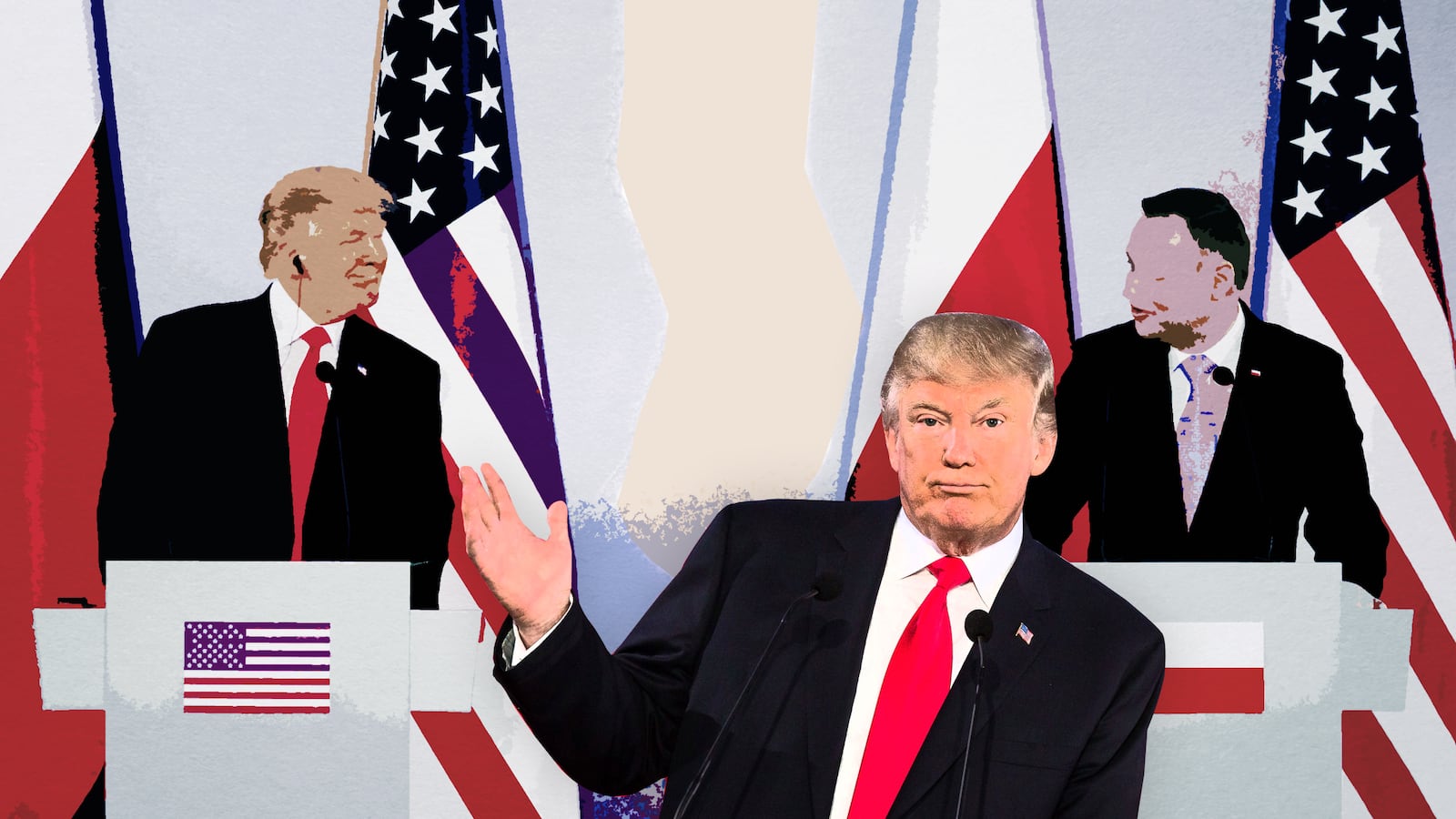

When Donald Trump came to Poland in July last year, it was a veritable love fest. The U.S. president praised the country effusively, its “so fantastic” people, and its history, which he highlighted as a shining example for all of the Western world on how to persevere, prevail, and fight for its identity. He even seemed to overcome his natural inclinations and criticized Russia. Needless to say, the illiberal Polish government—and even the liberal opposition—was ecstatic. Witold Waszczykowski, at that time still the foreign minister, even quoted Casablanca’s famous last line: “I think this is the beginning of a beautiful friendship.”

Eight months later, the friendship—which in living memory goes back over a quarter century—is at its lowest point in post-Cold-War history.

On Tuesday, Onet, a Polish news site, published a report later confirmed by my sources and Buzzfeed, that the U.S. State Department has communicated to Warsaw an effective ban on meetings between Poland’s most senior officials and the U.S. president and the vice president. What it amounted to, essentially, was “If you’re thinking of visiting the White House, don’t.”

The report was based on a secret Polish diplomatic memo informing Warsaw of a meeting between Polish diplomats and three State Department officials, the most senior among them being A. Wess Mitchell, Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs. During the meeting it was even hinted that some of the military cooperation projects between the two countries could be at risk.

The U.S. State Department issued what was seen widely in Poland as a classic non-denial denial, in which the department’s spokesperson Heather Nauert said that there was no suspension of “high-level dialogue with Poland,” but did not address the main substance of the reports: the informal ban on direct meetings between the leaders of the two countries. Meanwhile, the Polish Foreign Ministry’s own analysis published by Onet makes a direct mention of “blocked contacts with our chief ally.”

What caused this? The short answer is simple: a piece of legislation dubbed the “Holocaust law” by the media. The act, passed by Sejm (the lower chamber of the Polish Parliament) on the very eve of Holocaust Remembrance Day, stipulates that “whoever publicly and contrary to the facts attributes to the Polish Nation or to the Polish State responsibility or co-responsibility for the Nazi crimes committed by the German Third Reich” may face up to three years in prison.

It was meant as a mostly symbolic gesture: a sign that the government headed by the right-wing populist Law and Justice (PiS) party will no longer tolerate slandering Poland’s history and the recurrent mention of the misleading phrase “Polish death camps” in the international press. It was symbolic, because it is virtually unenforceable against foreign citizens and the foreign press. Nevertheless, it unleashed a diplomatic and public relations firestorm.

It whipped up unprecedented anger in Israel—until now a good ally. It has drawn widespread condemnation from the media from all over the world. And it produced perhaps the most spectacular example of the Streisand effect ever observed. The number of times the phrase “Polish death camps” was used skyrocketed overnight into millions (it even got into a Washington Post headline); it also focused the world’s attention on the one thing the government sought to hush up: the discussion of some Poles’ participation in the crimes against the Jews.

But most importantly of all, the passage of the act also provoked a disastrous chill in relations with Poland’s most vital ally, the United States.

The law itself was bad enough—it was described as “idiotic” even by the government’s allies at home—and would have caused outrage regardless of the circumstances. But the way the Law and Justice government handled the controversy made it much, much worse. It was a diplomatic train wreck.

Israeli and American diplomats have long warned Warsaw that the passage of the bill would cause negative reactions. And it should have been obvious that the administration that calls itself “the most pro-Israeli in history” would side with Tel Aviv. Yet when the law was passed by Sejm—and at the worst possible time, too—the reaction somehow caught the government by surprise.

The U.S. State Department issued a very strong statement, suggesting the law could damage “Poland’s strategic interests and relationships.”

“Taken literally, it was a diplomatic equivalent of firing a cannon,” says Michał Baranowski, director at the German Marshall Fund’s Warsaw bureau.

The Polish government then reportedly assured the allies it would introduce amendments to the law. But egged on by the ruling party’s hardcore wing, and trapped in its own propaganda about never giving in to outside influences, it didn’t. And, as I reported on Tuesday on the Wirtualna Polska site, when Rex Tillerson called Polish President Andrzej Duda to convince him not to sign the bill, Duda refused to accept the call. He reasoned that a secretary of state is beneath his diplomatic rank. Technically, he was correct (though it’s not unheard of for U.S. top diplomats to confer with heads of state), but politically, it proved to be a big mistake.

“The Americans were fuming,” a Polish government source told me.

The train wreck didn’t stop there. Speaking at the Munich Security Conference, and answering a question from an Israeli-American journalist, Poland’s Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki made a reference to “Jewish perpetrators” of the Holocaust, a stunning gaffe that immediately resounded all around the world.

“It’s not going to be seen as criminal to say that there were Polish perpetrators, as there were Jewish perpetrators, as there were Russian perpetrators, as there were Ukrainian ones,” he said, defending the new law.

“Obviously it was a mistake,” a prime minister’s aide explained to me. “But you have to understand the situation he found himself in. Speaking at the birthplace of Nazism, before the Austrian and German chancellors, and having to explain that Poland wasn’t actually responsible for Nazi crimes.”

Not that it mattered. Relations went downhill. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs A. Wess Mitchell (the successor to Victoria Nuland) even hinted that some aspects of security cooperation—by far the most important facet of the relationship to both countries—might be under threat, according to Onet’s reporting.

A U.S. congressional source and many experts say that is not likely. What is true, though, is that, as Mitchell reportedly said, the mood in Congress has markedly changed, which could complicate matters for Poland.

“It will take a while until emotions in the Congress die down. And potentially this is what is the most threatening in the long term,” says Baranowski. “The disagreement with the administration could be mended as soon as they settle the dispute with Israel, but in Congress, where public perceptions and public opinion matters more, it might not be so easy.”

For the United States, Poland is an ally of growing importance, especially in the face of a growing Russian threat. But for Poland, the U.S. is the ally, the guarantor of its security. And after picking fights with Brussels—which is threatening sanctions against Poland—irritating Germany, and irking Ukraine, the United States is the one country which Warsaw cannot afford to alienate. Thus, the diplomatic spat with Washington is major news here.

“By refusing to back down, the PiS government inserted Poland into the most serious diplomatic crisis in the last 27 years,” wrote Michał Szułdrzyński, editor of the center right daily Rzeczpospolita. “For Poland, the alliance with Washington is a question of geopolitical viability, and of whether or not we belong to the Western world.”

This sentiment was echoed by an internal analysis within the Polish foreign ministry. The document, quoted by Onet, says that “settling the dispute with the U.S. is more important than the feud with Israel or the talks with the E.U. over the question of rule of law.”

But precisely because the issue is so important to Poland, many PiS supporters are in denial. Even though the reports of the ban on meetings were later independently confirmed by Buzzfeed and Wirtualna Polska, the state propaganda machine, as well as privately owned pro-government media openly call it “fake news” and maligned the reporters who broke it.

It was not the first time Washington has expressed displeasure at the current Polish government’s illiberal course. U.S. diplomats have criticized—both publicly and behind the scenes—PiS judicial reforms aimed at politically subjugating the courts, as well as an ultimately revoked attempt to slap a big fine on a U.S.-owned broadcaster, TVN, for “irresponsibly” covering anti-government protests (dubbed by the government a failed putsch). But unlike the current crisis, those controversies eventually died down.

Polish officials are now scrambling to appease the U.S. administration. In quick succession, the authorities sent to D.C. the deputy foreign minister, a minister in charge of international dialogue, and now the president’s foreign advisor. It’s unclear if these visits made any difference. But ironically, Warsaw’s best chance at mending ties with the Trump administration may be precisely the thing the U.S. had previously criticized: the politicized judiciary.

The law may yet be voided by the Constitutional Tribunal, a court that rules on the constitutionality of enacted laws. Ever since PiS came to power and illegally captured the body, the institution has become a virtual tool of the executive. And while it’s doubtful whether the Holocaust law violated the Polish constitution, ultimately it doesn’t really matter. What does matter is whether the party—or rather its leader, Jarosław Kaczyński—decides if good standing with Trump is worth the political indignity of backing down.