Could a second-term President Donald Trump legally use military forces to conduct domestic law enforcement activities? The simple answer to the question is “yes.”

Beginning with George Washington, more than a dozen presidents have deployed troops more than two dozen times for law enforcement purposes. The most relevant federal law is the Insurrection Act.

In 1827, the Supreme Court concluded that an earlier version of the law gave the president the exclusive authority “to decide whether [an exigency requiring the militia to be called out] has arisen, and… his decision is conclusive upon all other persons.” Later versions of the law have not restricted the president’s power to decide whether an emergency exists.

That power does not exist in a vacuum. It arises out of the need for prompt actions in response to events like violent insurrections.

For example, that 1827 Supreme Court opinion originated in the War of 1812, when the British military invaded the United States, and the law in question stated that “whenever the United States shall be invaded, or be in imminent danger of invasion… it shall be lawful for the President [to call forth the militia] as he may judge necessary to repel such invasion.” (Italics mine)

The law’s core purpose has always been to provide tools for combating violent uprisings. President Washington invoked an early version of the law in 1794 to quell the Whiskey Rebellion against federal excise taxes on domestically produced “distilled spirits.”

Over the next two centuries, the law was amended several times, but events triggering its use generally have involved public violence, including efforts to oppress newly freed slaves in the Reconstruction-era South, violent labor disputes between workers and strike breakers in the 19th and 20th centuries, and riots in our cities—like those triggered by the murder of Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968, and the state court verdict in the Rodney King trial in 1992—where police officers were acquitted on charges related to King’s beating at their hands.

Unfortunately, the current version of the law contains broad language that a president unconcerned about traditional political and normative restraints on executive power could try to exploit in the absence of an actual rebellion or insurrection.

The Insurrection Act allows the president to use the military in three situations.

First, the law permits the president to send troops when asked by a state’s government to suppress an insurrection. The state must request help from the national government, but whether to grant the request is left to the president’s discretion.

Examples of how this might happen under a second Trump administration come readily to mind. A red state governor, say of Texas, might request that the president send troops to patrol the border with Mexico to control an “insurrection” against the state’s government caused by the “flood” of illegal immigrants. In response, the president could send members of the armed forces, the National Guard, or both.

But a request for help from the state is not necessary for the president to invoke the Insurrection Act. The law includes two sections permitting the president to act even if a state rejects offers of federal help.

One section authorizes use of armed forces to suppress “obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States” that the president considers to be unlawful, and which make it “impracticable to enforce” federal law in that state.

Stephen Miller looks on as Donald Trump meets with people in the Cabinet Room of the White House on Jan. 11, 2019, in Washington, DC.

Alex Wong/Getty

Again, possible actions by a second Trump administration come readily to mind. Is it possible that an adviser like Stephen Miller could persuade President Trump to send troops to our southern border to arrest groups—combinations or assemblages—of people because their actions, like leaving bottled water in the desert for immigrants and asylum seekers, are unlawful obstructions of government authority? Given their past words and actions, this seems possible.

Another provision of the Insurrection Act authorizes the president to suppress “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” that prevents execution of federal and state laws.

The potential scope of this poorly drafted statute is stunning. The law does not define the term insurrection, apparently leaving that decision for the president.

And the other examples, like domestic violence and conspiracy, do not necessarily require an insurrection. Given the history of the law, these examples might be limited to insurrection-related acts, like domestic violence in support of an insurrection or a conspiracy to wage rebellion. But an authoritarian president willing to exploit the statute’s imprecise and careless language might claim the authority to order troops to engage in regular law enforcement duties normally left to civilian police.

Daily gun violence occurs throughout the nation. We can imagine that a President Trump might rely on this language to send troops to Chicago to suppress that city’s seemingly endless gun violence, despite objections from the mayor or governor.

Of course, widespread opposition would erupt, constitutional objections would be raised, and eventually political and legal constraints might force the president to back down. But the initial decision to deploy troops from the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marines to act like domestic police officers appears to rest solely with the president.

Would that allow the president to use federal troops to suppress a “woman’s march” protesting the election of a president found guilty of sexual assault by a New York jury? An aggressive administration, unconcerned about constitutional rules and norms, might argue that the law’s broad text grants the president discretion to do that.

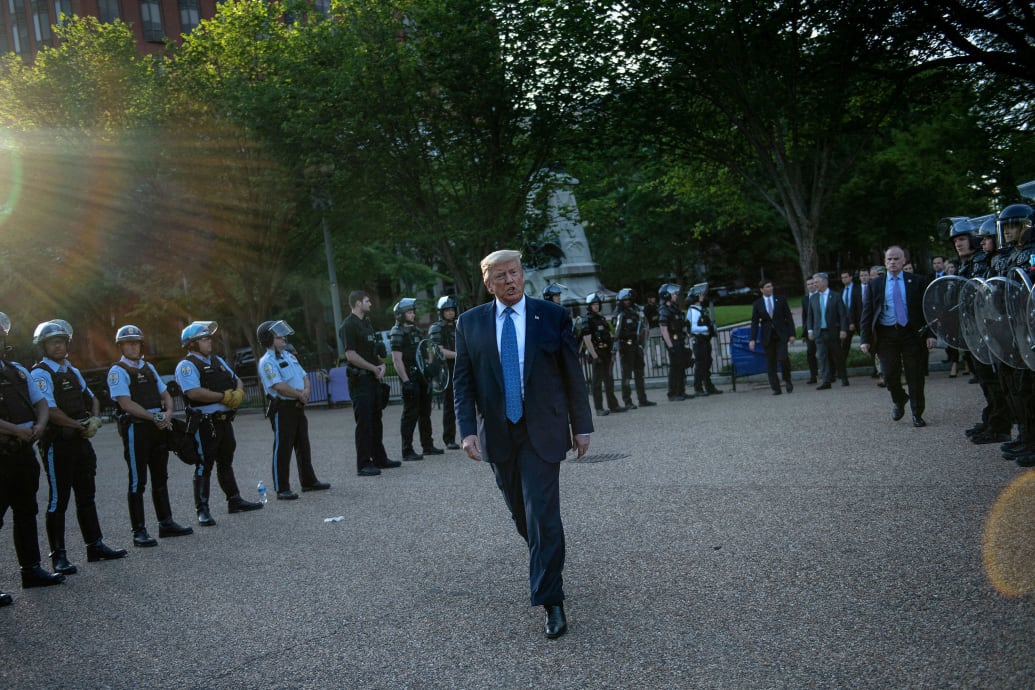

Donald Trump leaves the White House on foot to go to St John’s Episcopal church across Lafayette Park in Washington, DC, on June 1, 2020.

Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty

This authority is not nullified by the Posse Comitatus Act, which generally prohibits use of the military to engage in traditional civilian law enforcement. The Insurrection Act is an express legislative exception to this rule, despite the threats to democracy posed by military intervention in civilian life.

Since 2020, proposals to limit the president’s broad powers under the Insurrection Act have been offered by members of Congress and civil liberties organizations. None have been adopted.

The Supreme Court originally upheld an expansive grant of discretionary power to the president in part because it was “a limited power, confined to cases of actual invasion, or of imminent danger of invasion,” but also because it presumed that the president possessed high qualities of “public virtue, and honest devotion to the public interests.” This presumption may have been justified two centuries ago, but it would be an absurd delusion in a second Trump presidency.

In that same decision, the Supreme Court concluded that if the president abuses the power granted by the Insurrection Act, the remedies would be found in the “constitution itself… the frequency of elections, and the watchfulness of the representatives of the nation… to guard against usurpation or wanton tyranny.“

If these tools fail during the next 12 months, so might our democracy.