You wonder where President Trump gets some of the crazy stories he touts, like the one about U.S. Gen. John Pershing executing Muslim prisoners in the Philippines in 1913. “He took 50 bullets and he dipped them in pigs’ blood. And he had his men load his rifles and he lined up the 50 people, and they shot 49 of those people. And the 50th person, he said, ‘You go back to your people and you tell them what happened.’ And for 25 years there wasn’t a problem.”

In Trump’s mind, it was the ultimate deterrent. Except it’s not true. Pershing did lead American and Filipino troops in a brutal battle against holdouts in a southern island, but that’s it. There’s no evidence of the behavior Trump has praised, which would constitute a war crime.

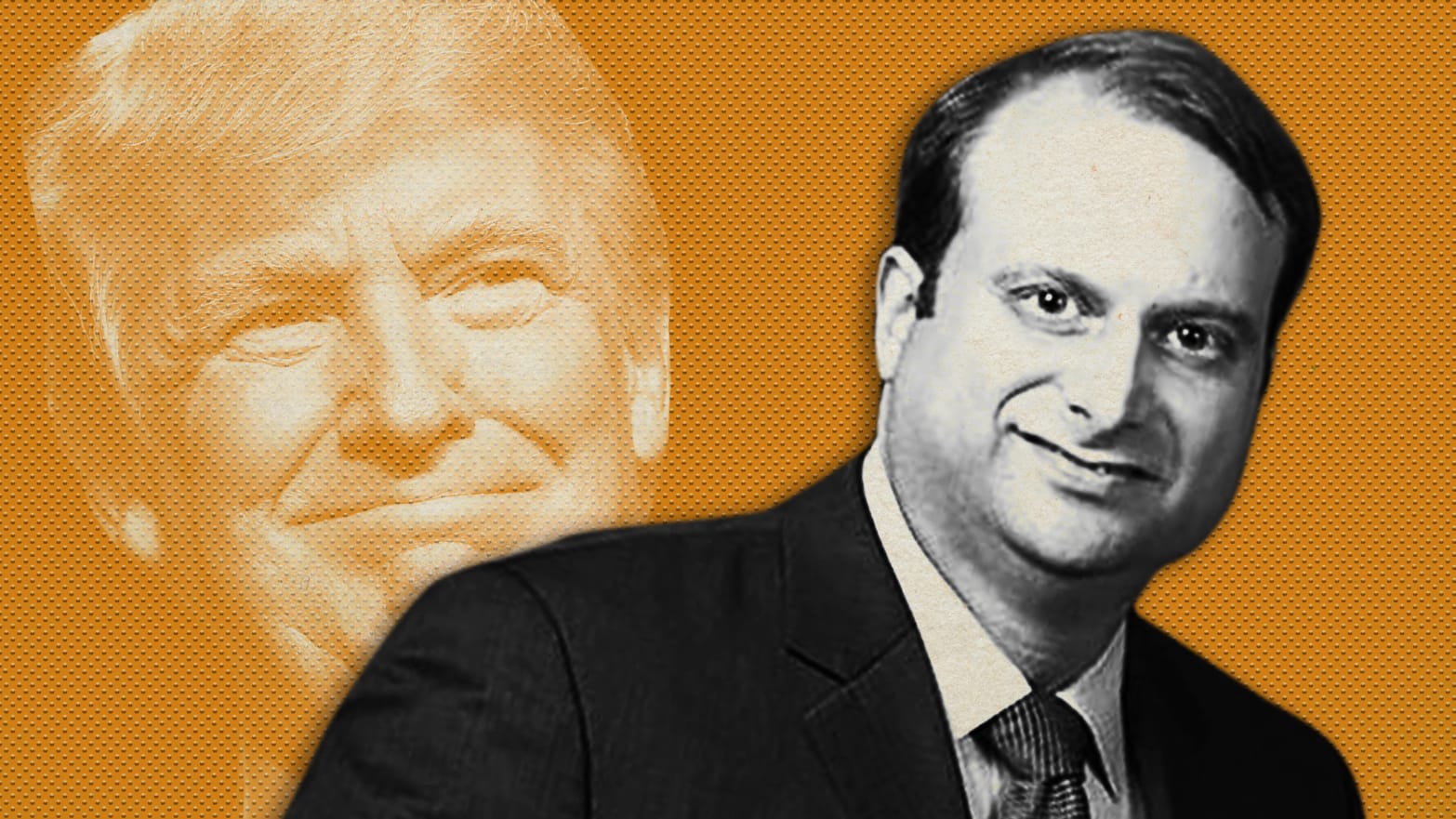

Yet people of a certain ideological bent have long embraced this story, and Steven Menashi, a special assistant and senior associate counsel at the White House, is one of them. Trump just nominated him for a lifetime seat on the federal bench for the Second Circuit.

Years before Trump brought it to national attention on the campaign trail, Menashi recounted the myth in a book review he wrote for the Hoover Institution Policy Review in 2002.

In Menashi’s telling, Pershing’s forces dipped bullets in pig fat and wrapped corpses in pigskin before burial in “a devastating contamination according to Muslim law,” Menashi writes. He quotes one U.S. officer reportedly telling the terrorists, “You’ll never see Paradise,” thus dashing their hopes of martyrdom.

“Pershing’s approach is probably no longer in the army’s counterterrorism repertoire, but the result was that guerrilla violence ended,” Menashi concludes, lamenting, “The American response to Islamic extremism has not always been so harsh—or as effective.”

“It’s deeply troubling that he pushed the myth that countless historians have debunked,” says Dan Goldberg, legal director at the advocacy group Alliance for Justice. “The job of a federal judge is to evaluate evidence, and here we have someone up for a judgeship willing to spread unsupportable information that is so prejudicial toward Muslims.”

Menashi, born in 1979, was at Stanford Law School at the time. He was in his early twenties and writing just after the 9/11 attacks, when President Bush worked hard to set a tone of leadership that tamped down anti-Muslim rhetoric.

At campaign rallies in 2016, Trump reveled in spreading this story while the crowd cheered. “So we better start getting tough,” he would bluster, touting his Muslim ban, his calls to build a wall, and his general demonization of immigrants as foreign elements to be rooted out.

In August 2017, after his first attempt at a “Muslim ban” had been struck down by the courts, President Trump tweeted, “Study what General Pershing of the United States did to terrorists when caught. There was no more Radical Islamic Terror for 35 years!”

The “pig’s blood” story has been around mainly on right-wing sites since a version of it first appeared as an email soon after the 9/11 attacks. Democratic Senator Bob Graham, then the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee, even shared it at a dinner party later in 2001.

More problematic for Menashi’s nomination may be the 65-page article he published in 2010 in the University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law, “Ethnonationalism and Liberal Democracy” (PDF). The paper is written in the context of Israel and argues that its identity as the Jewish state is compatible with being a democracy.

“Democratic self-government depends on citizens identifying with each other,” he wrote, making the case with examples from around the world that more ethnically heterogeneous populations have less effective government. “Ethnic ties provide the grounds for social trust and political solidarity,” he wrote.

MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow last week called Menashi’s article a “high-brow argument for racial purity in the nation state” that “ends with a war cry” that democracy can’t work unless it is defined by shared ethnicity. Maddow didn’t point out that Menashi, who is Jewish, pivots off of Israel to make his case, which got her significant pushback.

Robert McCaw, director of government affairs for the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR), said in a statement that “American democracy is founded on the principle that our rich national diversity is to be celebrated and that we as a people are united by our shared experiences and principles, not by our race or ethnicity.”

With so much political controversy swirling around Israel and Trump’s efforts to peel away Jewish votes in 2020, Democrats are likely to tread carefully on the issues around ethnonationalism that Menashi discusses in his article. But he has written a lot over the years, and Democratic staffers are just beginning to comb through everything. A self-described movement conservative, he is not shy about owning his opinions, exuding a stridency that with rare exception has not historically been associated with federal judges.

Before moving to the White House counsel’s office in 2018, Menashi was acting general counsel at the Department of Education, where he wrote in his Senate Judiciary Committee questionnaire, “I was responsible for providing legal advice related to all aspects of the Department's operations, including litigation, rulemaking, regulation, and enforcement. I supervised 110 lawyers in seven divisions in the Office of the General Counsel.”

That puts him on the hook for controversial policies put in place by Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, including rolling back civil rights and student loan protections that President Obama put in place.