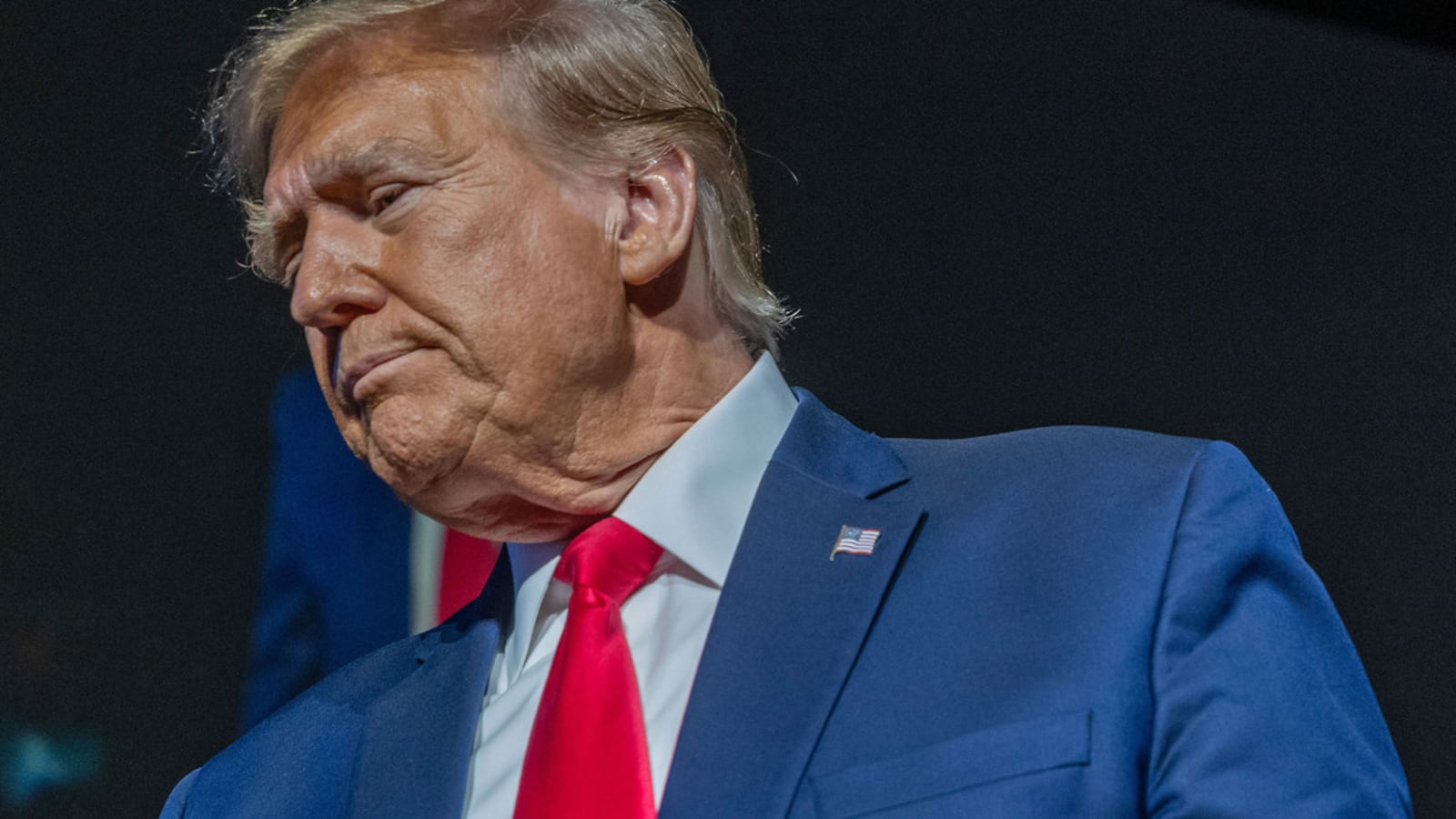

Donald Trump’s criminal trial against the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office is rapidly approaching. You may have heard about DA Alvin Bragg’s prosecution of Trump in New York. You may know that it involves “hush money” payments, adult film actress Stormy Daniels, and campaign finance violations. But what you may not know is just how serious this case is.

Bragg’s case charges Trump with 34 felonies for falsifying business records to hide from voters critical information during the 2016 presidential election. Prosecutors charge that Trump cooked his company’s books to hide his affair from voters because he was afraid that the story would hurt his candidacy.

This is no frivolous distraction about infidelity. It’s about democracy.

Bragg has effectively charged Trump with defrauding American voters by covering up some of the most consequential campaign finance violations in history. The charges allege Trump repeatedly lied to illegally conceal hush money payments he made to Daniels, his former mistress, to suppress the information to benefit his presidential campaign by avoiding a damaging scandal. Again and again. For months.

Trump knows how serious these charges are. In raising multiple arguments to dismiss, Trump threw everything but the kitchen sink at the prosecution. On Feb. 15, Justice Juan Merchan, the presiding New York state court judge, will hear those arguments and determine whether the case will proceed to trial, currently set for March 25, 2024.

It’s worth understanding the arguments Trump has made and why they are unlikely to derail the case.

Two of Trump’s arguments concern the timing of the case. First, Trump complains that Bragg delayed the prosecution to interfere with his presidential campaign—indicting him in spring 2023—even though news of his affair with Daniels broke in January 2018.

But the delay was justifiable. The DA’s office deferred to a federal investigation into similar conduct for nearly one year; Trump himself impeded the investigation for 17 months by filing a suit to block a subpoena for tax and financial records; and Trump was the sitting president, which raised constitutional questions about whether he could be prosecuted while in office. Additionally, prosecutors have wide discretion about when (and if) to file charges. There is no evidence of bad faith in the timing of the prosecution—just bad timing, perhaps, for Trump.

Second, Trump argues that the prosecution is barred by the statute of limitations—the law that sets the maximum amount of time to bring charges after the underlying conduct occurred, which for this crime is five years under New York law.

The 34 counts involve business records from 2017, so Trump’s attorneys did their math correctly: six (years) is more than five. Unfortunately for Trump, New York extended the five-year statute of limitations during COVID-19. Trump claims that the court should interpret that extension differently for criminal cases, but his argument is without merit.

Third, Trump argues that the case against him amounts to selective prosecution, i.e. that Bragg has pursued charges just because Trump is Trump.

The ex-president has consistently raised this defense against those suing him civilly or charging him criminally, but it has rung hollow before and will again now. Bragg’s office has filed felony falsification of business records against dozens of people and companies since he became DA. Despite Trump’s protests of unfair treatment, the facts show he has been treated the same as others who have appeared to engage in this type of criminal conduct.

Trump is also trying to dismiss the case based on the substance of the charges, claiming the indictment is legally defective in several ways. For example, he contends the records at issue aren’t technically business records because the hush money payments were effectively from the ex-president’s personal checkbook. However, the Trump Organization prepared, maintained, and updated the records. He also claims the grand jury was not presented with sufficient evidence of intent to defraud, but clearly the jurors saw enough evidence to indict. Both these arguments are destined to fail as factually and legally incorrect.

To his attorneys’ credit, Trump raises one interesting argument about the indictment being defective. The 34 counts in the indictment are all for falsification of records in the first degree, which require that the falsification was intended to commit or conceal another crime.

The DA’s office has explained that there were four other crimes that satisfy this requirement: violations of federal and state election laws, tax crimes, and the falsification of other business records. To understand how the DA’s office will prove that the 34 charged counts—covering 11 false invoices, 12 false ledger entries, and 11 checks—furthered these other crimes, let’s take a step back.

The DA’s theory of prosecution is that Trump and others engaged in the Daniels hush money payment scheme as part of a larger effort to bury information embarrassing to Trump during the campaign.

The Statement of Facts accompanying the indictment details a “catch and kill scheme” with David Pecker, the then-chairman and CEO of American Media, Inc. (AMI), the owner of the National Enquirer, and other supermarket tabloids.

Pecker agreed to be the “eyes and ears” for the campaign by seeking out and suppressing harmful stories about Trump and by publishing negative stories about Trump’s opponents. The Statement of Facts describes how AMI purchased the exclusive rights to a story that a former Trump Tower doorman was selling about a child Trump allegedly fathered out of wedlock—with the intention of not publishing the story. The story was later determined to be false, but the incident shows how the catch and kill scheme operated. Another example from the Statement of Facts involves payments AMI made to Karen McDougal, a former Playboy model, to bury a story about her affair with Trump.

To establish the first-degree felonies, the DA must prove the falsification of records violated federal election law by disguising the hush money payments as business expenses when they were legally campaign expenses. Or that the false records violated a broad New York election law that prohibits deception. Or that the 11 payments, made by Trump through his former attorney Michael Cohen, were misrepresented as income to Cohen when they were actually reimbursements, in violation of tax laws. Or that AMI and Cohen falsified their own business records to help conceal the hush money scheme.

Any of these object crimes would satisfy the first-degree requirement, which is why Trump’s motion to dismiss on this ground will not succeed. But what is interesting is how the proof of these other crimes will play out.

Will the court order the DA’s office to identify which object crime(s) go with which count? Probably not, but there are legitimate questions about how much leeway the DA’s office will have to present evidence of other crimes. And how will the prosecutors present a narrowly tailored case that does not devolve into an airing of Trump’s dirty laundry?

This second question is key. Much of the media attention has focused on the salacious context of the allegations. But this case is far more important than porn stars or Playmates.

At its core, the case is about a plot to deprive voters of information about a candidate for president—information that Trump and his allies believed to be damaging enough to hide.

It is unlikely that Thursday’s hearing will give Trump the victory he seeks. Instead, the case will be headed to trial next month, where Trump will face the music for his attempt to defraud voters in the 2016 election—in plenty of time before they decide whether to pull the lever for him in 2024.