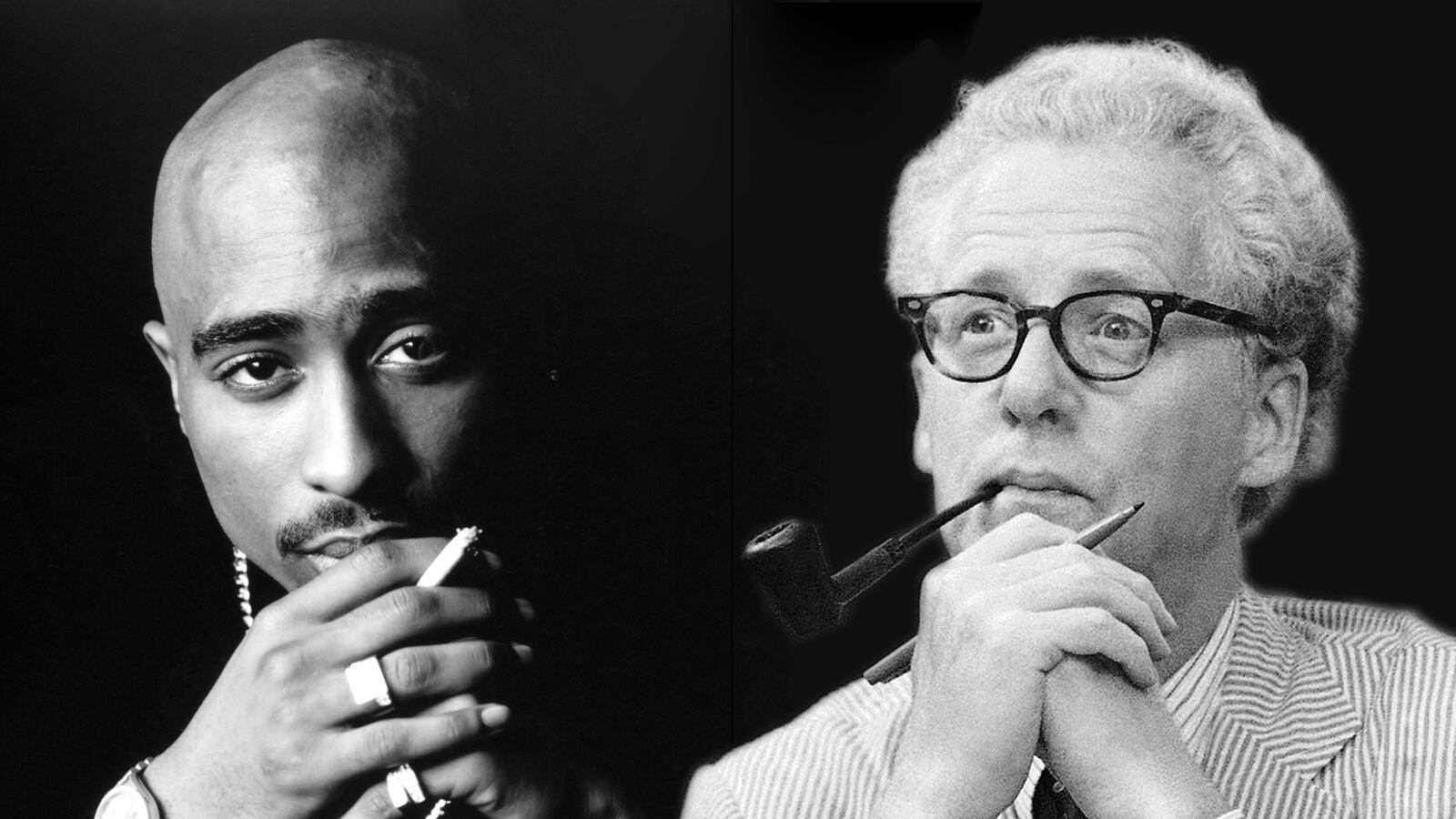

Tupac Shakur was still in his mother’s womb when she served as her own lawyer against charges that she and a dozen fellow Black Panthers had conspired to conduct a series of bombings in New York.

And as she did so, nobody admired Afeni Shakur more than the supremely insightful and devoutly decent newspaper columnist Murray Kempton. “No man who saw Afeni Shakur in those days could fail to be half in love with her,” Kempton later wrote.

He understood that her unborn child was at the center of her struggle.

“Tupac was conceived at some point during the trial jury’s selection,” Kempton wrote. “Common sense prescribed an abortion but Afeni declined to think of it. Her child must be brought to life and it would be for her to fight to keep him from being born to her in prison. That fight would be her timeless glory.”

She was initially freed on $100,000 bail, but was remanded after two of her co-defendants absconded. She would come into the Manhattan courtroom from the holding cells in jailhouse attire that contrasted with her increasingly manifest pregnancy and underscored what was at stake.

To Kempton, she was at her most magnificent on the afternoon when she rose to cross-examine Ralph White, an undercover detective she and her co-defendants had known as Yahwah.

“Afeni Shakur stood up for their engagement with her shoulders staunch and her stomach helplessly swelling with Tupac and with the supreme beauty that is the vulnerable girl asking with her eyes, ‘Why are you doing this to us, Yahwah?’” he wrote. “And then she transformed this using male from her antagonist to the sharer of common memories. She had somehow managed the miracle of crossing the great void between the rebel and the counterrevolutionary; and they began talking about her perilous and his endangering past as intimately as if they were alone.”

Kempton went on, “Near the end Afeni Shakur gently asked Ralph White if he had ever seen her do a bad deed. He replied that he couldn't remember her doing much and that all he knew was what she said.”

She concluded by simply saying, “I see.” The word “see” hung in the air as the detective stepped down.

“She went back in the dock to sit dreaming with Tupac, the work done of this day when it became impossible to think that she and her baby and the whole odd lot of her co-defendants had not been saved from jail,” Kempton reported.

Kempton recorded her summation in the prize-winning book he wrote on the case, The Briar Path:

“All we ask of you is that you judge us fairly,” she said at the end. “Please judge us according to the way that you want to be judged.”

Kempton subsequently offered what he reasoned to be mathematical proof of her powers.

“Their trial had lasted nine months and they were acquitted in two hours,” he wrote.

One month and three days after the acquittal, Tupac was born. Kempton occasionally encountered the proud mother over the next few years.

“Always with her laugh and always with Tupac in tow,” Kempton wrote.

He noted that she had enrolled her son in a music and art high school, where he studied acting and ballet. Tupac played the Mouse King in The Nutcracker.

“The street must have been the last destination she wanted for Tupac,” Kempton observed.

Kempton lost touch with her as she fell deep into drugs. Two decades had passed when he encountered her in another Manhattan courtroom, this time as the mother of a defendant. The son she had fought so gloriously to keep from being born in prison now faced being sent there. Tupac was charged with weapons possession as well as sodomizing and sexually abusing a 19-year-old fan who had come to his hotel room and ended up being set upon by some of his entourage.

The Mouse King had become a rap star. Kempton noted that Tupac had told another journalist, “My mother was a revolutionary Black Panther and all that. But I also saw my mother as a crack addict. So I answer to no one. I follow my heart.”

Kempton now suggested in purest Kempton-esque terms, “The child is well-advised to distrust any heart that instructs him to answer to no one.” Tupac, he went on to say, “has the privilege, if scarcely the right, to improve his image as one born to be a thug with the myth of a crack addict mother.”

Kempton allowed that Afeni “was sometimes wild and often wayward. … But the street addict type she could never have been,” Kempton insisted. “She was instead a heroic creature from the only too-familiar legend of the women of color whose fate it is to be goddesses stuck with sons and lovers much too mortal.”

During a midday break in the trial, Kempton had lunch with Afeni. He later reported that he “from decency, refrained from asking her about Tupac.” She reported without him inquiring that her descent into drugs had so angered Tupac that “he hardened his little heart against me,” but they had renewed their close bond after she had gone into recovery. She affirmed all that Kempton had believed of her as she expressed not just support for her son, but admiration for the accuser’s mother.

“When I look at her,” Afeni said, “I am proud to be a mother. She says nothing, looks straight ahead at everything, and sits by her child. She is so … so … so elegant.''

On the day that the jury began its deliberations, Tupac and some hangers-on headed for a Manhattan recording studio. They encountered two genuinely tough Brooklyn gunmen in the lobby who ordered them to lie down. The hangers-on immediately complied, but Tupac refused and was shot three times before he was relieved of his jewelry. The cops who responded included Police Officer Craig McKernan, who had arrested Tupac on the sex abuse charges the year before.

“Hey, Officer McKernan,” Tupac said.

“Hey, Tupac, you hang in there,” McKernan said.

Blood was oozing from the wounds to Tupac’s groin, scalp and hand.

“Just tell me if I'm going to die,” Tupac said.

McKernan asked Shakur who shot him.

”I didn't even see it,” Tupac the self-imagined tough guy replied.

But, as pain followed the initial shock, the supposed tough guy called for his mother.

“The first human creature Tupac Shakur felt the need to cry out for in his pain was not a friend but his mother,” Kempton noted. “The young may wander the world round; but, when the terrors of the night ask too much of them, they always turn to their mothers.”

Kempton added, “The burden of Tupac Shakur's sins cannot be dismissed as a light package to carry; but neither can the weight of the fame and the commodity value that you have won all by yourself before you were given time to grow up. Only part of you is the roaring and now and then clawing lion; the rest is still the little boy.”

Kempton considered the irony that Tupac was on an operating table as the victim of a violent crime at the very time a jury was asking for transcript readbacks in his case. There was also a further irony.

“But the courage of his defiance aside, where are we to find the true glory of Shakur's refusal to permit three armed and rapacious strangers to treat him as though he were no more than a thing?” Kempton asked. “What he was affirming was the fact of his own dignity; and he would not be waiting out his jury now if it had not been for one young woman's insistence upon asserting hers… They appear to possess in common a redeeming sense of dignity.”

Kempton reported that the day before the shooting Tupac had allowed to reporters in the courthouse hallway that the young woman might not have felt compelled to press charges if he had made at least some small gesture of kindness and respect.

“From whence except in hindsight can we be blessed with even a hint of the intrusions of repentance?” Kempton inquired, going on to say of Tupac, “His future is for his jury to appoint. I must confess to a fugitive and irrational wish that he might find some small mercies there. It may not be entirely unreasonable to hold on to some hopes for a sinner whose first thought in a bad moment is to call up his mother.”

Tupac insisted on discharging himself from the hospital before the doctors felt he was ready and was still clad in a hospital gown when he was rolled in a wheelchair past a waiting media scrum. He was again the tough guy.

“I can’t believe I’m wearing polyester,” he said.

Tupac returned to court in a wheelchair, a Yankee cap over his bandaged head. He was acquitted of weapons and sodomy charges, but convicted of sexual abuse.

“Now he has brought himself close to ruin by treating his imaginary Tupac as if it were his real self,” Kempton wrote of the tough guy persona. “That, I’m afraid, is show business.”

Kempton attended the sentencing and described Tupac as “a half-man, half-child who had become a star without ever even having been a bit player.“ Kempton watched Tupac being led from the courtroom to begin a term of 18 months to 4 and a half years.

“The jauntiness of his bearing was a portent of the long watches of the nights ahead when laughter stops and weeping fills all that’s left; and the last thought was a prayer that the tears ahead will wash him back to the better self that has until now fought the worse one and lost,” Kempton wrote.

Tupac did indeed find prison so harrowing that he soon reconsidered his gangsta ways.

“In here, I don’t even remember my lyrics," Shakur was quoted saying. “If thug life is real, then let somebody else represent it, because I’m tired of it.”

Kempton had proven so right in so many ways that he should not have been surprised when Afeni asked him to begin visiting her son in prison and assume a role that struck him as dauntingly improbable.

“A father figure,” Kempton told me.

Kempton was, after all, a white Episcopalian of tweedy appearance and intellectual bearing who pedaled about the city on a three-speed bicycle, puffing on a pipe and listening to classical music on his Walkman.

“It is scarcely fair of us the aged to judge rap when we have but listened and lost interest too soon to hear it out,” Kempton wrote about hip-hop. “But a fleeting impression suggests that rap has a tendency rather to numb as, for all I know, narcotics might.”

Yet, Kempton had clearly discerned the core of Afini’s struggle to save her child from being born in prison when she was 25. There seemed a good chance Kempton could help Tupac through his own struggles now that he found himself in prison at the age of 25.

In his true heart, Tupac was not a rap star, but a poet. And he might very well have felt the power of such poetic symmetry. Just as Kempton had once watched Afeni perform the miracle of crossing the distance between herself and an undercover, Kempton might have been able to connect with the son of the woman he called a goddess.

But then Marion (Suge) Knight of Death Row Records flew in on a private jet. Tupac signed a three-page handwritten recording contract and Knight posted $1.4 million to bail him out pending appeal. Shakur departed Clinton Correctional Facility in a stretch white limo.

“I know I'm selling my soul to the devil,” Tupac said.

Knight was the gangsta’s gangsta, and Tupac returned to thug life with such swagger that he seemed to be atoning for having been so shaken by prison. He then seemed to have renewed misgivings. He had begun speaking of leaving Death Row and settling down into family life in September of 1996, when he was shot again, this time while in Las Vegas, with fatal results.

“Tupac Shakur triumphed too fast and grew up too slow,” Kempton wrote.

He identified the turning point as Tupac’s decision to escape prison by signing with Death Row.

“Every sad and bitter tale has its hour when the doom inevitable in the long run becomes inescapable in the short,” Kempton wrote.

Kempton was aware that many of Tupac’s fans were themselves not of the street. “Were they really so much his devotees as the greedy spectators and willers of the doom that seemed willed by and for him but never for them?” Kempton wondered. “The pop artists who die young are especially cherished as surrogate martyrs for adolescents in the comfortable circumstances that offer assurance against real suffering. How pleasant it is to weep for those who died for us and thereby expanded our smugness with one more proof of the cruelty of the social arrangements that happen to be so conveniently gentle to ourselves.”

Kempton gazed back from the end of the tale to its start.

“Finally, after all the maunderings in contemplation of the waste of Tupac Shakur's life and all about it, the mind settles on the memory of a woman in jail and the light in her eyes and the baby six months in her womb,” he wrote.

Kempton recalled of the younger Afeni, “For all she knew she might be in prison for 20 years, and still she chose to have her baby.”

Kempton said of the son, “He was a chosen child and a testament to a faith no less noble for having a reward no better than this.”

Kempton summed it all up in the Kempton way:

“Afeni Shakur does not, I am sure, regret the choice.”

Eight months later, Kempton himself died, at the age of 79. Had he survived until this age of Twitter, he would have seen proof of his conclusion about Afeni in her tweet on June 16, marking the 43rd anniversary of the victorious day her son was born outside prison.

“Happy birthday! I love you.”

She further celebrated the event by attending a preview of Holler if You Hear Me, the Broadway musical she is producing that features and celebrates Tupac’s music.

She was beaming.

Kempton would have loved it.

And only Kempton could have done such a moment justice.