“Believe women” has been the rallying cry of the #MeToo movement, but after Oct. 7, as an American Jew who has watched many human rights and feminist groups turn a blind eye to the sexual violence Hamas unleashed on girls and women in Israel, I ask: Where’s the “me” in MeToo? Why is no one believing the women in Israel?

And I’m not alone.

Ahead of Nov. 25’s UN’s International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, the Israeli Foreign Ministry initiated the hashtag campaign #BelieveIsraeliWomen and announced a task force to investigate the sexual atrocities Hamas perpetrated against women and children on Oct. 7—after media attention, indifference from the international human rights community, and pressure from Israeli women’s groups.

Shortly after Oct. 7, an independent organization of international human rights experts and women’s rights groups in Israel formed the Civil Commission on Oct. 7 Crimes by Hamas against Women and Children. Concerned that no Israeli or international organization was documenting Hamas’ sexual violence, it set about collecting evidence of Hamas’ gender-based assaults and encouraging government bodies to further investigate these atrocities as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Even as the first women and children hostages are being released and Israel’s Health Ministry has instructed the hospitals treating them to have women doctors and nurses on hand to conduct all physical exams, how to check for and document signs of rape and torture, and how to interview without retraumatizing them, the UN has shown little sign of caring whether Israeli women suffer violence, and hasn’t rallied for Red Cross access to those still held captive by Hamas.

UN Women executive director and under-Secretary General Sima Balhous, waited until Nov. 22 to first mention that she was “greatly alarmed by reports of sexual and gender-based violence,” but failed to mention the culprit was Hamas and the victims Israeli and foreign nationals.

Earlier this month, the hashtag #MeTooUnlessURAJew spread widely on social media as grassroots women’s groups in Israel and abroad launched campaigns to express outrage at the silence of the international community regarding the growing evidence that Hamas engaged in systematic rape on Oct. 7.

Women’s rights groups in Israel—including Bonot Alternativa, one of the organizations leading the nine-month-long protests against Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s anti-democratic judicial reform in Israel—marched in solidarity with the Hostage and Missing Families Forum. A group of medics also called attention to the heightened health risks of female captives, who range in age from infants to teens to elderly women with heart disease, diabetes, asthma, and other health conditions, to say nothing of the mental health repercussions of such trauma.

But many prominent American feminists like Angela Davis have outright victim-blamed Israel, more interested in throwing around terms like “colonial feminism” than actually advocating for women. Others, like the avowed anti-sexual violence activist known as V (formerly known as Eve Ensler), in a long statement never acknowledged the shocking kidnapping and torturing of girls and women in Israel on Oct. 7—which Hamas was all too proud to share on social media, but that she carefully avoided mentioning. (This silence about systematic rape is coming from the same person who once said, “we should all be hysterical about sexual violence.”)

To them, I ask: If you can’t stand with all women, what do you stand for? How is rape an act of resistance?

Liad Gross, 36, weeps as she holds up a sign for her missing friend Sagui Dekel Chen, during a demonstration outside the Ministry of Defense headquarters in Tel Aviv, Israel, Oct. 24, 2023.

Marcus Yam/Los Angeles TimesThe Civil Commission on Oct. 7 Crimes by Hamas against Women and Children is no longer waiting for these inhumane human rights celebrities to respond. They’ve begun collecting evidence of Hamas’ sexual violence and encouraging government bodies to further investigate these atrocities as war crimes and crimes against humanity.

“I wish I could go back in time,” says Dr. Cochav Elkayam Levy, the head of the new commission and a professor of International Law, Human Rights and Feminist Theory at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. “I could never have imagined taking on this unimaginable task.” As she described her commission’s daunting work, the evidence they’ve gathered so far and the deafening silence of the global community, she paused to catch her breath in between tears.

“I thought my colleagues in human rights agencies would condemn such horrific attacks,” Elkayam-Levy, a 20-year scholar of international and human rights law, says. “I thought pretty naively that we must write to them and send them a report.” After issuing a short draft of her findings (signed by 160 prominent law and human rights scholars) to officials at the UN and its various bodies, including UN Women and the Committee on the Rights of the Child, her commission received no response.

“The fact that they keep silent is not just an insult to Israeli victims,” she says. “It’s an insult to all victims. International law loses its meaning when you fail to condemn the same crimes when they’re perpetrated against Israeli citizens, it weakens the legitimacy of global institutions, and it allows further violations not just in Israel but globally.

“The denial and silence of the international community provides fertile ground for the weaponization of women’s and girls’ bodies in warfare,” she adds. “If international law doesn’t apply to us, do they even consider Israeli women human? Seems like we’re not part of humanity.”

After the commission presented its case at a virtual forum called, “The Unspeakable Terror: Gender-Based Violence on Oct. 7,” hosted by various Jewish student groups at Harvard University a week ago, the group has gained traction.

So far the UN has shown no signs of caring whether Israeli women suffer violence. This can be interpreted as callous indifference, or outright victim blaming. You’d have to be under a rock not to have watched the many searing images of Hamas’ massacre in Israel, the most brutal of which featured women.

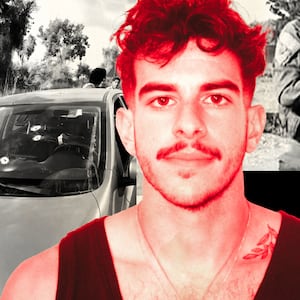

There was Noa Argamani, the young woman at the Nova Festival in Re’im, her eyes full of fear, crying for help as masked terrorists sped off with her on a motorbike. There was the naked, limp body of German-Israeli tattoo artist Shani Louk, shown on the back of a pickup truck paraded down the streets of Gaza like a prized hunting kill, as onlookers cheered and spat on her. She has since been confirmed dead, per DNA samples taken from skull fragments. She was decapitated. Her family is unable to give her a Jewish burial.

There was also Shiri Silberman-Bibas, clutching her 9-month-old and 3-year-old sons, sobbing as terrorists screamed and pushed her around. Subsequent Israeli police reports and footage released by the IDF show mothers who were sadistically killed by Hamas. Among them, charred remains that were later identified as a mother clutching her baby as they were burned alive.

As someone who’s spent the past decade researching and documenting an untold story of slavery and sexual violence committed against Jewish women during the Holocaust, I recognized the pattern. Parents killed in front of children, children snatched from parents, families broken up, women stripped naked, corporally humiliated, raped in front of loved ones and in public—these forms of sexual violence were tactics the Nazis employed, but they never documented and for which they were never held accountable. The world turned a cold eye to Jewish women then, just as it is doing now.

It took more than 50 years from the end of World War II for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) to recognize rape as a weapon of war and prosecute perpetrators as war criminals. Ever since, there’s been a growing awareness of how gender-based violence (GBV) is used to terrorize and break up the fiber of a society and commit genocide.

The body of a woman represents the body of a nation, says Prof. Ruth Halperin-Kaddari, director of the Rackman Center for the Advancement of the Status of Women at Bar-Ilan University in Israel. There is no clearer symbol of genocide than systemic wartime sexual violence.

The violation of a body is a particularly heinous war crime, a wound so deep, it takes years, if not decades, for survivors to confront it. When it came to the Holocaust, most women, including my own mother, took such brutal truths to their graves. And their perpetrators were never indicted, charged, or even acknowledged.

The 2002 Rome Statue of the International Criminal Court recognized the systemic use of rape, sexual slavery or trafficking, forced pregnancy and sterilization, and other forms of bodily violation as war crimes and crimes against humanity. As Democratic Republic of Congo gynecologist Dr. Denis Mukwege, who won a Nobel Peace Prize in 2018 for his work to end rape as a weapon of war, has said: “the woman who gets raped is the one who is stigmatized and excluded for it… We need to get to a point where the victim receives the support of the community, and the man who rapes is the one who is stigmatized and excluded.”

It was heartening to see Dr. Mukwege and global human rights organizations like UN Women swiftly condemn Russian forces for violating Ukrainian women and children shortly after they launched their invasion. So why aren’t they advocating for the women and children of Israel?

Even worse than their deafening silence is the ensuing gaslighting of Hamas’ 1,200-plus civilian victims—which include nationals from over 40 countries—UN Women waited until Oct. 20 to issue its first statement, in which it only condemned Israel. It made no mention of Hamas’ raped victims in Israel, or the quarter-million Israeli civilians displaced in Israel, nor did it push for humanitarian aid for the hostages held by Hamas. This glaring double standard isn’t just cruel, it makes a mockery of UN Women.

“We have been completely betrayed by the international community,” says Halperin-Kaddari. “The betrayal is not only to the hostages and to the victims of sexual abuse, but to the very integrity of the institutions, and of the international human rights framework at large.”

Halperin-Kaddari, formerly the vice president of the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) for 12 years, says in that role she advocated for women no matter their nationality, from Yazidi women trafficked by ISIS in Iraq to women in Central Africa and the DRC to Sri Lanka.

“But the level of the cruelty and brutality of Hamas against women and children in Israel on Oct. 7—nothing matches that,” she adds.

And that’s no exaggeration. Among the atrocities cited by rescue units are gang rape until a woman’s pelvic bones were broken and her legs twisted in unnatural positions, and genital mutilation. Israeli Police Chief Kobi Shabtai said a pregnant woman’s belly was sliced open and her fetus removed while she was alive, and that women’s breasts were sliced off and tossed around as if they were volleyballs, and that there were reports of necrophelia.

Perhaps because of this commission’s visibility, the Israeli government has finally announced the formation of its own task force investigating sexual violence on Oct. 7—something it failed to do as it began the gruesome and daunting task of identifying and burying the dead. Israeli police said they collected more than 1,000 statements and over 60,000 video clips and testimonies of rape, though it’s not clear whether any of the victims survived.

Police photographs of the carnage at the kibbutzim along the Gaza border and at the Nova Festival show women’s bodies, naked from the waist down, legs spread, blood visible, and underwear pulled down. One festivalgoer told police of a gruesome gang rape she witnessed:

“They bent her over and I realized they were raping her, one by one. Then they passed her to a man in uniform. She was alive. Standing up and bleeding from her backside. They were holding her by the hair. One man shot her in the head as he was raping her, while he had his trousers down, they cut her breast off.” In other words: she was murdered while her rapist was still inside her.

These sorts of testimonies have been confirmed by morgue workers, including a woman volunteer at Shura military base near Tel Aviv, who spoke of “very bloody underwear.” Another, Alon Oz who was tasked with identifying the remains of hundreds of soldiers, spoke of “women burnt with their hands and feet bound… I saw gunshot wounds to private parts, bursts of gunfire, shots to finish someone off, a missing head, and missing limbs.”

Though this sort of forensic evidence aligns with the type of systemic sexual violence that is considered a war crime, some, like Israeli Arab Knesset Member Iman Khatib-Yasin, said there was no proof rape occurred on Oct. 7, though she refused to watch footage of the Hamas massacre shown to Knesset members. She later recanted her denialism.

An investigation by The Times of Israel found there was little physical evidence collected of the victims of Oct. 7, including rape kits, which have a 48-hour window. In that time, Israel was still an active combat zone, and by the time investigators were able to access victims, bodies were in such a bad state, the retrieval of semen and DNA samples wasn’t possible or a priority. Many scholars say the lack of rape kits doesn’t matter, so long as factors like intention to commit large-scale rape as a weapon of war have been established.

Dr. Elkayam Levy points to an Arabic-Hebrew glossary purportedly belonging to Hamas and discovered among the carnage that instructs how to say 50 sexually explicit terms like “take your pants off” in Hebrew as evidence of war crimes. This is in addition to testimony from captured Hamas terrorists in which they revealed they were ordered to rape, behead and dismember as many civilians as they could, and even were given permission from their imams to do so because such atrocities go against the teachings of the Quran.

Dr. Mehnaz Afridi, director of the Holocaust, Genocide and Interfaith Education Center at Manhattan College calls such exemptions a total corruption of the teachings of the prophet Muhammad, who strictly forbade violence against women, children and the elderly, even during wartime, unless it is in self-defense As for the lack of rape kits to prove there was sexual violation perpetrated, she says such standards were never employed in the tribunals of Rwanda or Bosnia, the latter of which bears resemblance to Oct. 7.

“This attitude of proof is and has always been a problem in terms of the victimization of women and sexual violence during the war,” says Dr. Afridi, a Muslim woman.

As to why so many human rights and women’s groups are denying that Iran-backed Hamas engaged in genocidal acts and crimes against humanity, Prof. Halperin-Kaddari says there’s only one conclusion: antisemitism.

And many concur, including exiled Iranian women’s activist and journalist Masih Alinejad, who highlighted the fact that wiping the Jewish state off the map is at the core of Iranian and Hamas terrorism. Muslim reformer Asra Nomani—a former Wall Street Journal correspondent and friend of the late Daniel Pearl who was beheaded by al Qaeda terrorists in 2002—spoke out against Susan Sarandon’s antisemitic statement that “frightened” Jews are getting a taste of what it “feels like to be a Muslim in America.”

“Antisemitism can run deep to the point that those antisemites will always dehumanize the other, whether women or children,” says Dr. Afridi.

Fortunately, some university presidents are acting against antisemitic academics who are promoting Oct. 7 denialism.

On Saturday, the University of Alberta, Canada, fired the director of its Sexual Assault Centre for signing a letter denying sexual violence was perpetrated by Hamas on Oct. 7.

Meanwhile, David Katz—who heads cybercrime at Lahav 433, the Israeli police’s criminal investigation division—says it may take six to eight months to complete their investigations. But Halperin-Kaddari and Elkayam-Levy are holding out hope the world will respond sooner.

“The lead prosecutor of the International Criminal Court gave a speech in Cairo expressing interest the Oct. 7 atrocities,” says Elkayam-Levy, who will be meeting with diplomats and UN representatives in New York toward the end of the month, while Halperin-Kaddari will be bringing the case to Geneva. They have filed three petitions, one in the name of women, one by women’s rights organizations and one signed by international law scholars.

“It will be a new international tribunal,” she says, “representing victims from all around the world. In a year, we may get to the end of the beginning of our work.” As she adds, Israeli society has never encountered sexual violence on such a massive scale and there is so much that will sadly remain unknown because so far no victim of sexual atrocities has survived.

And that’s what makes the gaslighting of the global feminist community so particularly painful.

“One of my very early decisions was to collaborate with allies who show moral clarity on these issues,” she says. One of these was Prof. Catharine McKinnon, a feminist legal scholar whose work has laid the foundation for rape as a weapon of war.

“She’s a non-Jewish American professor and we weren’t sure how she would react,” she says. “But the moment she said: ‘I know you’ve been through hell. I hope you’re OK,’ we all began to cry. This is what it means to be believed.”

Marisa Fox is a journalist and filmmaker whose upcoming documentary, My Underground Mother, reveals an untold story of women’s camps and sexual violence perpetrated against Jewish teenage girls during the Holocaust.