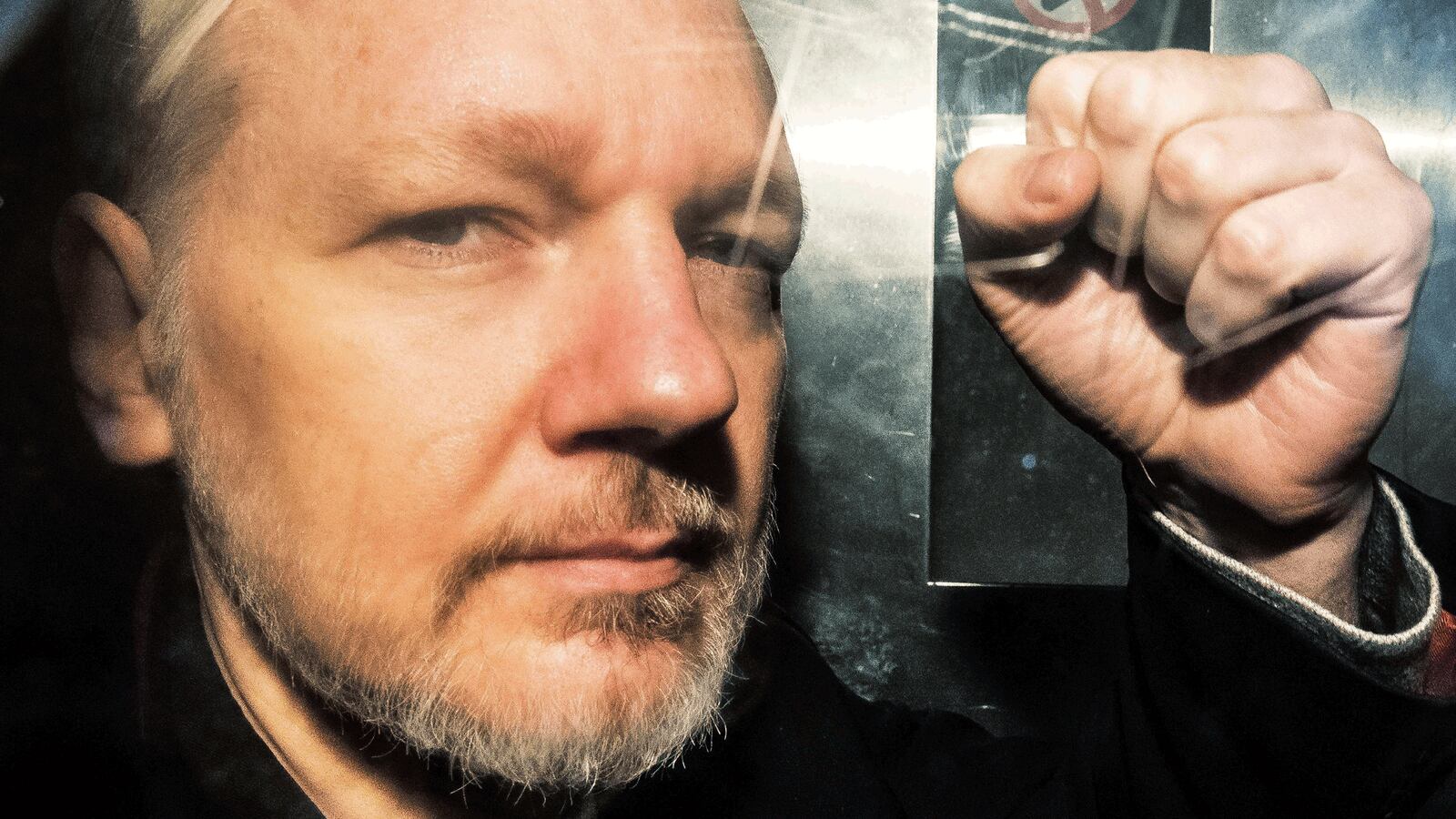

In a stunning escalation of the Trump administration’s war on the press, the Justice Department has indicted WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange for revealing government secrets under the Espionage Act. It’s the first time a publisher has been charged under the World War I-era law.

The indictment charges Assange with 16 counts of receiving or disclosing material leaked by then-Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning in 2009 and 2010. The charges invoke broad provisions of the Espionage Act that make it a crime to disclose or retain any defense information knowing it “could be used to injure” the U.S. The act has no exception for reporters or publishers, but prior administrations have balked at invoking the law against journalists for fear of colliding with the First Amendment.

The Justice Department immediately sought to draw a distinction between Assange and the press in a briefing for reporters announcing the new indictment.

“The department takes seriously the role of journalists in our democracy and we thank you for it,” said John Demers, head of the department’s National Security Division. “It has not and never has been the department’s policy to target them for reporting. But Julian Assange is no journalist.”

Demers cited WikiLeaks’ publication of the names of U.S. government sources, saying it endangered people in China, Iran, and Syria.

WikiLeaks on Twitter called the prosecution “the end of national security journalism and the First Amendment.”

Assange is currently serving an 11-month sentence in the U.K. for jumping bail in a Swedish rape investigation, while the U.S. pushes its request to extradite him to the United States on computer hacking charges revealed in April. He was kicked out of the Ecuadorian embassy in London that month after taking refuge there from authorities for seven years.

The leaked documents comprised 250,000 State Department cables, 90,000 Army field reports from Afghanistan and 400,000 from Iraq, and 800 detainee assessment briefs from Guantanamo Bay. Assange released most of that material without redaction, and the new indictment claims that the U.S. sources identified in the leaks were put in harm’s way as a result.

“By publishing these documents without redacting the human sources’ names or other identifying information, Assange created a grave and imminent risk that the innocent people he named would suffer serious physical harm and/or arbitrary detention,” the indictment alleges.

He is also charged with two counts of conspiracy for allegedly working with Manning to violate the Espionage Act and the anti-hacking Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

The FBI and federal prosecutors in Alexandria, Virginia, first began investigating Assange in 2010 and amassed a wealth of internal WikiLeaks chats and documents from informants and subpoenas. But the Obama administration was reluctant to indict Assange.

A former senior Justice Department official told The Daily Beast last month that the Trump administration saw Assange’s case as a way to pursue its war on leaks.

“There was renewed interest under the new administration to revisit issues of what qualifies as the media and to look back at the Assange case,” said Mary McCord, who was acting head of DOJ’s National Security Division.

Despite the barrage of leaks in the years following the Manning disclosures, there were signs as early as 2017 that the Justice Department was still focused on the leaks that first put WikiLeaks on the map.

A witness at the grand jury proceedings that produced Thursday’s indictment told The Daily Beast that prosecutors were specifically probing Assange’s reluctance to redact his leaks for any reason.

“They showed me chat logs in which I was arguing vehemently with him about releasing documents that would leave people vulnerable and put people’s lives at risk,” said David House, a former WikiLeaks volunteer, in an interview last March. “That was the only thing they put in front of my face that made me think, ‘This may be what they’re going after him for.’”

No U.S. sources are known to have come to harm as a result of the leaks, likely in part because of a massive remediation effort launched in the weeks before Assange published the material.

The indictment takes pains to distinguish WikiLeaks from conventional journalism outfits in other ways as well, quoting Assange’s own description of his site as an “intelligence agency of the people” and lingering on Assange’s chats with Manning in which he encouraged and guided the soldier in the leaking. It also claims Manning deliberately sought out military secrets that were listed on a “most wanted leaks” section on WikiLeaks’ website.

None of this is strictly relevant to the Espionage Act. If the Justice Department included these details to make the Assange prosecution more palatable to journalists and free speech advocates, it’s not working.

“Any government use of the Espionage Act to criminalize the receipt and publication of classified information poses a dire threat to journalists,” said Bruce Brown, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press in a statement.

“This is an extraordinary escalation of the Trump administration’s attacks on journalism, and a direct assault on the First Amendment,” said the ACLU’s Ben Wizner. “It establishes a dangerous precedent that can be used to target all news organizations that hold the government accountable by publishing its secrets.”