When people ask if I’ve ever seen anything like what’s happening today, my stock answer is 1968.

We had two assassinations, anti-war protesters in the streets, cities torched and burning, and thousands of young men coming home in body bags from a war everybody hated but couldn’t end.

There are parallels between then and now, a feeling of apocalypse with an old order breaking down, of events spinning out of control. Fifty years ago, a generation of young protesters challenged our institutions, and our government. Today, the president is the one defying norms, testing the limits of his power as we rely on those same institutions to stay strong—our courts, the Congress, and the media.

I was working as a “Girl Friday” in the Atlanta bureau of Newsweek on April 4, 1968, when Martin Luther King Jr. was shot as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, where he had addressed striking sanitation workers the previous day in his campaign for economic justice.

The editors in New York assumed that riots would erupt in Atlanta, Dr. King’s birthplace and headquarters for his civil rights organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. To prepare, we were sent gas masks. I still have mine, in the basement. I’ve never used it.

Non-violence was at the core of Dr. King’s teachings, and it was a tribute to him that the city that was his home, and where he co-pastored with his father the Ebenezer Baptist Church, remained calm. Atlanta called itself then “the city too busy to hate,” and its progressive white mayor, Ivan Allen Jr. walked the city’s neighborhoods in the aftermath of King’s assassination, and led the way in a police car for thousands of black students to march peacefully in King’s memory.

Remembering these events 50 years later prompted me to pick up the phone and call a friend in Atlanta who helped me report the aftermath of Dr. King’s death. I wasn’t yet officially a reporter, and I don’t think Xernona Clayton thought of herself as a source. But she was close to the King family, and she talked to me about those terrible days, and how she helped Coretta King through them.

“I drove him to the airport to go to Memphis, and after Memphis, he came home in a box,” she began. She stayed with the four young King children when their mother went to Memphis, and she handled all the decisions and details for Coretta, her clothes, the head dress she wore at the funeral, making sure her hair was done, knowing the eyes of the world were upon her.

Jack Garofalo/Paris Match via Getty Images

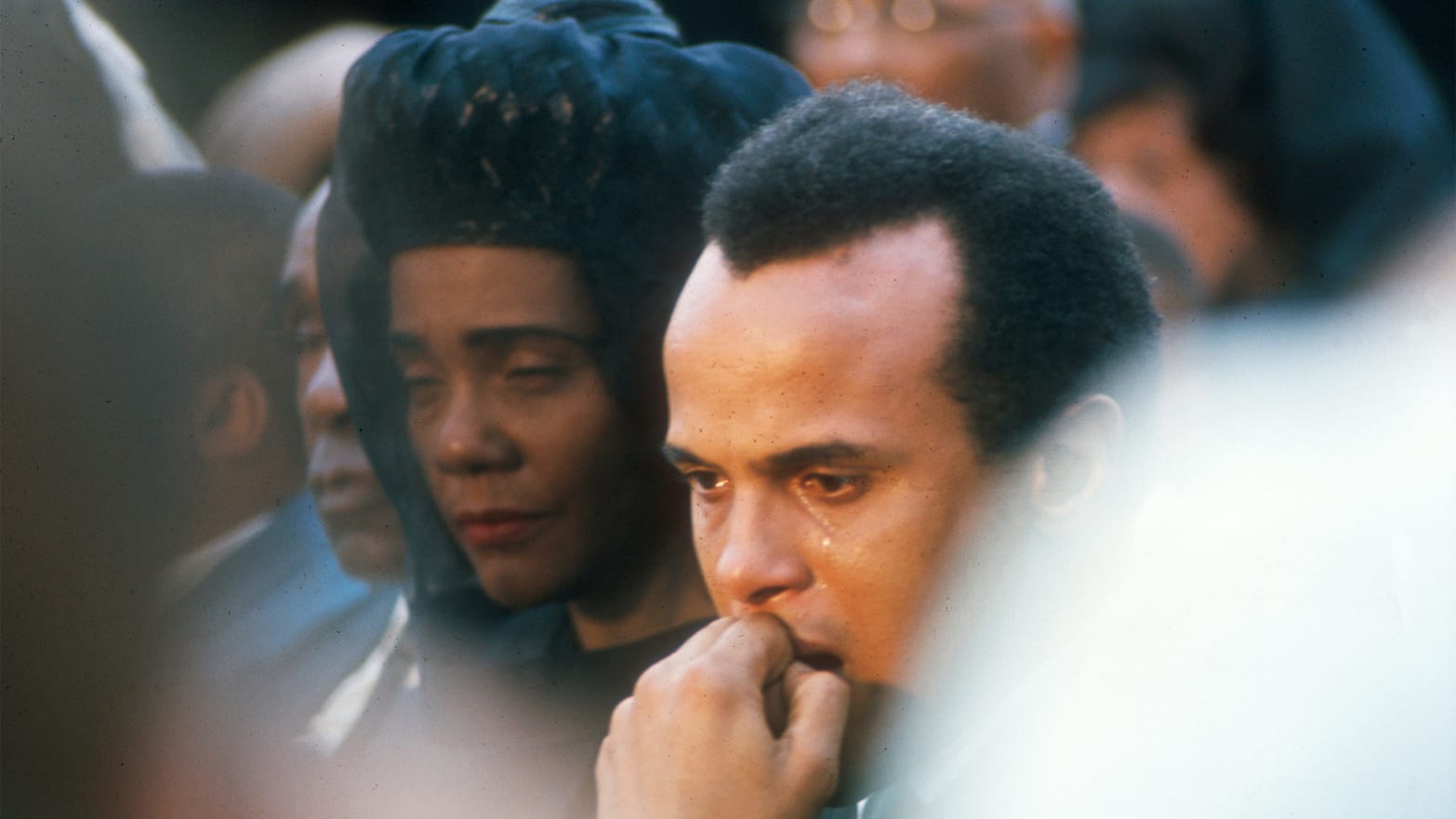

With Dr. King’s birthday coming up 50 years after his death at age 39, Clayton has done a number of interviews. A civil rights leader and broadcast executive, she told me, “The main thing journalists zero in on is when I saw him in the casket.” She and Harry Belafonte and his wife, Julie Robinson, were the only non-members of the family to view King’s body when he first arrived back in Atlanta from Memphis.

“I saw Coretta almost lost her balance, I thought it was the shock of seeing him and what had happened, but when I got down to the bier, someone had picked up a whole glob of clay and slapped it on his face. I eased over to the mortician—it was clay red—and asked, ‘is there anything you can do?’ And he said loudly and crassly, that’s the best I can do. His jaw was blown off.”

She turned to Dr. King’s mother, who was dark-skinned, and asked if she had any loose powder. Then she asked Belafonte’s wife, who was white, for the same thing. Both had compacts with loose powder, and she made a combination, smoothing it on King’s face to tone down the clay while Belafonte placed a handkerchief under King’s neck.

King would lie in state at Morehouse College, his alma mater, through the day and night, and Clayton came back at midnight to touch him up. When the casket was moved to Ebenezer Baptist Church, she applied powder before they opened the doors in the morning, and again in the afternoon to make it, she said, searching for the right words, “more palatable.”

“How did I do it?” she wonders now. “I didn’t have time to think, I just acted.”

At the King home, Coretta’s bedroom was in the rear of the house, and Clayton would help her decide who she would personally see, and when she would emerge. Jackie Kennedy was coming, then she wasn’t coming, then she was coming, then she canceled again, saying she was not sure she could handle it. “Finally she did come. Coretta had me escort her from the front of the house to the back room, and they embraced for what seemed like 20 minutes. It wasn’t that long, it just seemed that way. Nothing was said in words. It was the communication with no narration of two people who’d been through the same thing.”

Even after King’s death and then two months later, the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, after he had won the California primary, and would have been the Democratic nominee for president, Clayton says, “We could see work we were doing had some payoff. The man there now [Trump] is saying to us, don’t look for no payoff. He’s putting us in our place as African Americans. He’s doing something every day to make us uncomfortable. He doesn’t give us a ray of hope.”

Those of us who came of age in the turbulence of 1968 have a perspective that can lead us to believe this too shall pass, that we’ve seen worse—or that we’re in a situation of such high instability that anything is possible, including civil war.

Bill Galston, a political scientist with the Brookings Institution, was a first-year graduate student at the University of Chicago when King was assassinated. Chicago was one of the cities where violence and flames erupted, and there were days when he and his soon-to-be wife weren’t sure it was safe to be out driving. The social fabric of the country was strained to the breaking point.

“1968 has long been my nominee as the single worst year in America since the civil war—and in hindsight, I have no reason to withdraw that judgment,” Galston told The Daily Beast. “Cities aren’t burning the way they were. Generations aren’t separated from each other like they were. We aren’t, thank God, in a war that divides the country [like Vietnam]. In 2016, we didn’t see anything like the Democratic convention of 1968 with people in the same party yelling epithets at each other.

“My view which I’ve articulated to anyone willing to listen is that we will get through this—our institutions are strong enough even if our leadership is at best mediocre.”

Todd Gitlin isn’t so sure. He teaches journalism at Columbia University, and in 1963 and 1964 he was the president of SDS, Students for a Democratic Society. Looking back, he marvels that activists of his generation remained hopeful up until the moment Kennedy was killed, and even after, that out of the turbulence, there would be a new politics more responsive to the people.

“Hope had a lunatic edge,” he told The Daily Beast. Kennedy was on the verge of knitting together a coalition of blacks and whites, and after his assassination, Democrat Hubert Humphrey ran on the “politics of joy,” an absurdity in retrospect, says Gitlin, who like many young activists did not vote for Humphrey, only to regret it, “and rightly so,” he says, after Richard Nixon narrowly won the election.

“The [anti-war] movement was absurdly indifferent to how it was perceived by the rest of America. We were running around in the streets getting our heads bashed in, and it felt like a kind of moral victory that we were still alive. The Gallup [poll] found a majority thought the police were right. We destroyed the Democratic Party, now it was on to the revolution.”

The cutting edge of the left voted for Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver. Others wrote in comedian Dick Gregory. “I didn’t vote in 1968, for which I’m not proud,” says Gitlin.

Nixon skillfully mobilized the “silent majority” and from 1968 to 1992—24 years—Democrats were in the wilderness with the sole exception of Jimmy Carter, who won election in response to Watergate.

If getting through 1968 means we can get through anything, Gitlin does not share that optimism. He’s not sure where we’re headed. Several scenarios are possible, some pretty normal—Trump gets vanquished at the ballot box in 2020—and some apocalyptic and wild. “I don’t discount civil war,” says Gitlin, outlining a scenario where Republicans are turning up the pressure, they want him to resign, and he says “No. Fuck you.”

What do Republicans do then? What does he do then? “He’s wired in a different way and the forces are unpredictable,” says Gitlin. If 1968 is a roadmap, no one knows where it leads.